(photo by Jim Goodwin)

(photo by Jim Goodwin)

Sally Rogers: No Time to Feel Hopeless

by Leslie Zak and Joanie Calem

What can one little person do? For the answer, look no further than Sally Rogers, this year’s Magic Penny recipient. An exceptional singer, songwriter, performer, educator, and activist, Sally is the embodiment of CMN’s mission and an inspiring member of the CMN community. She’s been active on the CMN Board of Directors, served as BOD President, and worked tirelessly in the background on various advisory boards, including PIO!’s. Over the years, she has contributed insightful interviews, feature articles, and eminently singable, heart-lifting songs to the journal. Sally’s song leading at conferences is legendary. As CMN member Dave Kinnoin says, “She sings like an angel!”

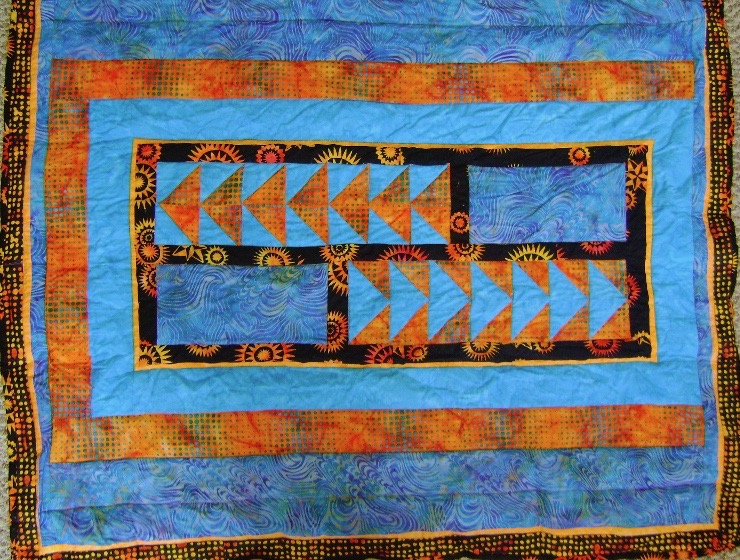

This Way Out Quilt

This Way Out Quilt

Sally is also an artist and quilter who contributed her talents to the creation of two collaborative quilts used at CMN conferences and fundraisers, blending her love of music and quilting. She was a co-founder of Quilters: Piece for Peace, which made three quilts that were raffled off to support the Connecticut Nuclear Freeze Campaign. One was on the cover of her recording Love Will Guide Us. “Sewing is as important to me as my music,” Sally said in our interview. She began sewing in childhood and started using an old Singer machine at age ten.

Sally credits her mother for both her love of sewing and her love of music. “My mother was a pianist and the organist for our church. She was a talented accompanist, but never pursued a career because of needing to tend her babies. However, she was a gifted piano teacher, and taught until she was seventy-eight.” Sally soaked up the ever-present music in her home and spun it into gold. Her father played cornet, a brass instrument similar to a trumpet, and the home was always filled with good music of all genres: “I remember my mother playing Bach and Debussy—wonderful stuff!”

Nuclear Freeze Galaxy Quilt (detail)

Nuclear Freeze Galaxy Quilt (detail)

When Sally started college, she was interested in studying music therapy. Though she had already begun her career as a folk singer, accompanying herself on guitar, she found that guitar was not thought of as a “serious” instrument by the music schools she considered attending. Voice, however, was a “legitimate” instrument, so she auditioned as a singer. She got into music school at Michigan State University (MSU) in East Lansing and began taking voice lessons. Though the voice lessons were often a struggle, with her teacher saying, “Don’t use your folk singer voice,” the lessons helped her use her voice more effectively. She had suffered throughout her childhood from asthma and chronic colds, coughs, and sinus infections, and her university vocal training helped her discover ways to use her voice despite it all.

Throughout her time as a student at MSU, Sally kept busy working at the local music store, Elderly Instruments, ordering books and running their school of folk music. She also helped run the local coffeehouse, the Ten Pound Fiddle. Because of her work at these venues, she befriended many touring musicians who were passing through East Lansing. Thanks to the encouragement of Canadian songwriter Stan Rogers (no relation!), who encouraged Sally to drive to Toronto to audition at a performers’ showcase, Sally was invited to appear in Winnipeg and at several smaller festivals that jumpstarted her career.

She has performed and recorded sixteen albums, and early on became one of a small number of artists (at the time) who recorded specifically for children. Her Peace by Peace album was widely acclaimed, and her next works, Piggyback Planet: Songs for a Whole Earth and What Can One Little Person Do? received national awards. Her songs can be found in both national music textbooks (“What Can One Little Person Do?” and “Love Will Guide Us”) and in the Unitarian and Quaker hymnals (“Love Will Guide Us” and “Circle of the Sun”).

“Lovely Agnes”

In 1979, Sally composed “Lovely Agnes” for her grandmother’s ninety-second birthday. She never intended to sing it to anyone else, thinking no one would be interested in such a personal story. Her grandmother’s memory was failing at the time so Sally wrote the lyrics on a card, which her grandmother kept in a basket of cards next to her knitting chair, with the thought that it would be rediscovered each time she picked it up. Sally happened to sing the song to Lisa Null, one of those touring musicians passing through town. Unbeknownst to Sally, Lisa taught the song to her friends Claudia Schmidt, Lisa Neustadt, Jean Redpath, and Helen Schneyer. This foursome sang the song on Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion in 1980, leading Garrison to write a note to Sally: “Don’t be surprised if you run into ‘Lovely Agnes’ in your travels. It sounds like an old song.” Then he invited her to come on the show whenever she was in the area. This led to twelve appearances on the show over the next five years.

Claudia Schmidt and Sally Rogers, 2017 (photo by Ruth Smith)

Claudia Schmidt and Sally Rogers, 2017 (photo by Ruth Smith)

The next year, Sally was invited to sing at the North Country Folk Festival in Ironwood, Michigan. Sally considers this event, run by local art gallery owner Phil Kucera, to be the best example of a true folk festival. It was extremely well run and included not only musicians but traditional storytellers and craftspeople. Phil had the idea that Sally should meet Claudia Schmidt, so he made sure both women were at the festival in 1981. It was there they first sang “Lovely Agnes” together, and they have been performing together fairly steadily ever since. Their album We Are Welcomed celebrates their thirty-fifth year together.

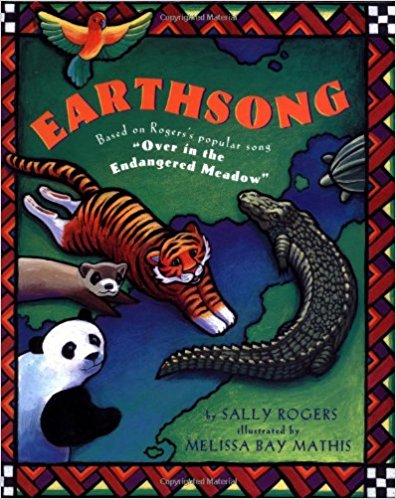

Sally also wrote a wonderful parody of the folk song “Over in the Meadow” called “Over in the Endangered Meadow.” A literary agent suggested that she turn her song into a picture book, which resulted in Earthsong. Getting the book published was an interesting challenge. The agent connected Sally with Putnam Penguin Publishing House, but it took seven years for the publisher to find an illustrator. Once one was selected, Sally had no expectation of meeting the illustrator, as publishing company policy dictates that writers and illustrators are kept separate from one another. But the illustrator was also having problems with the publishing company, so breaking with protocol she called Sally, and together they finished the book. It was in print for over ten years, which is an impressive run for a children’s book. Sally said, “I was just at a school the other day. Some of the kids had just seen the book and were extremely excited that the author was here at their school.”

Sally’s song “What Can One Little Person Do?” was written for a school principal in Kentucky, though she doubts he has ever heard it. Sally said, “I performed at an old brick schoolhouse in a small town in Kentucky back in the early ’90s. I walked into the school and found institutional green walls and trophy cases, but no sign of school children. My immediate thought was ‘The principal must be a coach or a former military man.’ I felt very guilty thinking such stereotypical thoughts and tried to wipe them from my mind. When I got myself set up to perform in the gym, students literally marched into the room silently and sat in straight rows, each row a measured distance from the one in front of it. When the principal entered the room, wearing a crew cut and a green polyester leisure suit that matched the school walls, once again my thoughts turned to the military and to sports. I introduced myself to the principal, shook his hand, and politely asked what he did before he was principal. He said proudly, ‘I was the coach!’ and after a short pause he continued, ‘but that was after I taught PE for a few years and I served in the military.’ It being February, I then asked him, ‘So what have you been doing in your school to celebrate Black History Month?’ His response was, ‘Why, nothing at all! We don’t got no black students here.’ I wrote ‘What Can One Little Person Do?’ for him, with his students in mind.” This song was one of twenty-four songs included in the songbook and CD I Will Be Your Friend.

CMN has exerted an influence on Sally’s work since the beginning. When CMN was first founded, Sally was an enthusiastic “gathering” attendee. She supported the creation of CMN and was in on discussions among the founders. “CMN came at a good time for me,” she says, “because I was starting to do more work with kids—in schools and elsewhere.” Though she was an accomplished performer with in-school experience, at the conferences she took on the role of learner. She met CMN members who worked with children in ways that she could not as a stage performer, was intrigued by the possibilities, and increasingly found that many activities she loved to teach in her music classes came from people she met at CMN gatherings: Ann Barlin, an early CMN member and creative dance pioneer; Sarah Pirtle; Bob Blue; Joanne Hammil; Stuart Stotts; Bruce O’Brien; Ruth Pelham; and many others. “I looked around [at a gathering] and saw all these wonderful, talented people devoting their lives and art to making this a better world.”

Sally possesses an uncanny ability to look around a room and find the music, and many of her beloved songs were inspired by events at CMN conferences. “We’ll Pass Them On,” an anthem that closes nearly every CMN conference, was inspired by a keynote address given by Pete Seeger in Warwick, New York, in 1993. Sally’s then five-year-old daughter, Malana, was sitting on her lap as she listened to Pete, and the song lyrics tumbled forth onto a spaghetti-soaked napkin that had survived lunch. Sally also remembers fondly the 1994 CMN conference in Petaluma, California, when Nona Beamer was the keynote speaker and taught that Hawaiian chants are like prayers, ending with the words “in the name of children.” This reminded Sally of Christian prayers, and in response she wrote a song for Nona called “In the Name of All of Our Children.”

Sally also credits CMN for giving her permission to cut back her touring as a folk performer. Sally and her husband, Howie Bursen (who Sally says is the best banjo player in the world specializing in “melodic claw hammer banjo”), toured together when their daughters, Maya and Malana, were young. Sally says, “Seeing so many people in CMN able to make a living doing children’s music encouraged me to do the same, because I had been travelling all over the world singing, and it was becoming harder to do that with two kids. I was looking for ways to make a living and stay at home. So I started moving a little in that direction. I could work in schools locally and be home in time to meet my daughters getting off their school bus.”

In 1997, Sally was chosen to be the Connecticut State Troubadour. The honorary position was created in 1991 to encourage cultural literacy and promote the state of Connecticut through music and song performances. At the time, there were no obligations for the Troubadour and no compensation. But Sally turned it into an opportunity to get grants for a three-school historical songwriting residency.

The family: Howie Bursen, Maya Rogers-Bursen, Sally, Malana Rogers-Bursen (photo by Joan Sherman)

The family: Howie Bursen, Maya Rogers-Bursen, Sally, Malana Rogers-Bursen (photo by Joan Sherman)

She was inspired by the 1996 Connecticut court case Sheff v. O’Neill, in which an African-American family in Hartford claimed the state was maintaining segregated, separate, and unequal schools. The family won their case, and though everyone agreed that something needed to be done, no one knew how to bring about actual change. It was decided by the court that every town in Connecticut would create a diversity committee, and that each committee would catalog the diversity in their town in terms of economic status, religion, ethnic identity, and more. Building upon this, Sally decided to create a project where kids from different schools could meet each other and work together through pen pal correspondence and autobiography writing. The goals were to make new connections, teach children about local history, and finally write songs using primary resources and oral histories as catalyst.

Using her role as State Troubadour, Sally raised money from the Quinebaug and Shetucket Rivers National Heritage Corridor (now the Last Green Valley), the Topsfield Foundation, and the Connecticut Office of the Arts to create the project with students from three diverse schools. One was in Thompson, an old mill town, one was an urban school in Willimantic, and one was Sally’s own rural town, Pomfret. Fourth grade classes from each school participated in the project.

With help of the local historical societies in each town, Sally located elders from each community who were willing to be interviewed. Each class interviewed one person, chose one of the stories they had heard, and turned that story into a song. Twelve songs were created. Sally then wrote one additional song for each class using primary sources. At the end of the project, 150 students along with their teachers (many of whom were musicians) performed all twenty-four songs at a final concert. It was truly a community effort. Sally’s leadership also permanently changed the expectations for State Troubadours, who are now required to organize at least three cultural events during their term.

Passport: China. Chinese New Year’s Dragon, Cultural Arts Week, 2004 at the Pomfret Community School

Passport: China. Chinese New Year’s Dragon, Cultural Arts Week, 2004 at the Pomfret Community School

In that same year, Sally was invited to help write four folk operas for a Mennonite community in Newport News, Virginia. Based on oral histories, an area that Sally is passionate about, the operas told the stories of the six Mennonite communities in the area. Fittingly, the performances took place in the Yoder Barn Theatre, a Newport News performance space that had been converted from the last Mennonite dairy barn in the region. Sally wrote the music and Jo Carson—playwright, poet, author, and NPR commentator—wrote the script. Although called “folk operas,” the plays were more like musicals, as they included speaking parts. Sally says of the experience, “I learned a great deal about their community and was honored to be included in their lives. Working with Jo Carson was more fun than I knew you could have.”

In 1992, Sally began volunteering at the Pomfret Community School in Pomfret, Connecticut, which her daughters attended. From 2001 to 2010, Sally served as the music specialist, four days a week, which allowed her to continue residency work in other schools and perform on weekends. During her tenure, Sally created an ongoing project still in existence in which the whole school studies a different country for the course of the academic year. Sally recalls, “This project was also an outgrowth of the local diversity committee. We had very few people of minority ethnicities in our school, so this program was a way to introduce our students to people from other cultures.”

Sally’s students at the Pioneer Valley Chinese Immersion Charter School in Hadley, MA, 2016, performing their sound composition on recycled instruments

Sally’s students at the Pioneer Valley Chinese Immersion Charter School in Hadley, MA, 2016, performing their sound composition on recycled instruments

The Fish Basket Goddess: a bilingual Mandarin/English opera created by the Second Grade class of 2012 at the Pioneer Valley Chinese Immersion Charter School, under the direction of Sally Rogers

The Fish Basket Goddess: a bilingual Mandarin/English opera created by the Second Grade class of 2012 at the Pioneer Valley Chinese Immersion Charter School, under the direction of Sally Rogers

Science of Sound (photo by Maria Carpenter)

Science of Sound (photo by Maria Carpenter)

When the students enter kindergarten, they receive “passports,” and each year they get their passports stamped. By the time they get to eighth grade, they have a full passport with their pictures from kindergarten. At the end of each school year, the study culminates in an weeklong celebration, in which docents (parents, community volunteers, and people from the country of the that year), visit each classroom, and present different aspects of the country and its culture: traditional celebrations, language(s) spoken, holidays, clothing, geology, history, food, and more. Guest artists are invited to perform music, theater, dance, and storytelling. The celebration kicks off with an exposition in the form of a “marketplace” on the stage, with food and costumes, posters, and artifacts. Scavenger hunts take place in which the students receive clues to help them learn more details about the country. The celebration week ends with an evening performance and dinner of representative food, often catered by a local restaurant that specializes in food from that country.

From 2011 to 2016, Sally taught K–4 music at the Pioneer Valley Chinese Immersion Charter School in Hadley, Massachusetts. Drawing on what she learned in a summer course through the Boston Lyric Opera Company and her own past experience, Sally and the second graders wrote three operas based on Chinese folk tales. Two of the operas included bilingual portions, written with help from the Chinese teachers at the school. The students accompanied themselves on Orff instruments and had the opportunity to perform all three of the operas at the school. Two were presented in 2012 and 2013 at a festival at Wheelock College in Boston.

When asked what she would like to convey to those of us in the world of children’s music, Sally says, “In these days of electronics and technology, many children are rarely or never exposed to live music or given the opportunity to make music themselves. My friend Papa John Kolstad once had a child approach him after a school assembly program, asking, ‘Hey mister, where’s the radio in your guitar?’ as if he had no idea that John was himself generating the music he had been listening to. Once I was at a puppet show assembly for kindergarteners in the school where I was working. When it was over, one of the students said, ‘Can we watch that video again?’ as if he was unaware that real people were standing in front of him performing. This is very troubling to me, and implies that many young people have no idea that real people perform, even on those programs they watch on their electronic media. I want all kids to know that music is something they CAN participate in. We all carry our voices with us wherever we go and we all can sing. Music is one of the very things that make us human.

“In working with children, it is always important to listen to them, to their concerns, to their passions, and to their dislikes. I really wish I had written down the many wise things that have come up in conversations with kids.

“I always come away from a gathering/conference renewed by knowing that there are such fine professionals in charge of our children’s cultural lives. CMN is dedicated to giving children back their voices and helping them to be heard. This is so important in a democracy, especially in these times. We must use our voices well, loud, and often, and know that what we think and do matters. CMN is one of the few places where we who work with kids can go to nurture our OWN hopeful spirits. I know I return home each year after the gathering with renewed buoyancy, reminded that what we do not only matters, but is essential to the well being of the world.”