Judith Cook Tucker (photo by Phyllis Tarlow)

Judith Cook Tucker (photo by Phyllis Tarlow)

Walking the Talk: You Just Have to Have a Big Heart

An Interview With Judith Cook Tucker

by Sally Rogers

For seventeen years, Judith Cook Tucker has been at the helm of World Music Press (WMP), a publishing house specializing in multicultural music shared by master musicians from the cultures represented by the music. Her publications include books, CDs, and octavo scores, all of which have been used by teachers across the country searching for authentic and culturally sensitive music for their students. Her goal was to wed ethnic music with classroom music teachers nationwide so that children could be exposed to world music within the context of their home cultures.

More recently she has founded the Connecticut Folklife Project [now defunct]. The organization’s website states their mission as follows:

The guiding purpose of the Connecticut Folklife Project is the enhancement of intercultural understanding through music and the folk arts. We locate master artists who are maintaining their traditional heritage arts while living in the North American cultural mosaic. Whether they are musicians. dancers. carvers, storytellers, costumers, instrument builders, or have skills in any of a number of other areas, we document, preserve, present, and revitalize their work.

This exciting new project provides a model for similarly dedicated organizations that work to celebrate, validate, and share with each other the cultures in our communities, with respect and joy.

Sally Rogers: So what brought you to the whole issue of multicultural music and children and education?

Judith Cook Tucker: My mother was a musician and the dance partner of a very well-known folk dancer. During the WPA [Works Progress Administration] in the late 1920s, early 1930s, she led a demonstration group of children who traveled all over Manhattan by subway to do international folk dance and song programs in schools for other children. In doing that, she developed a repertoire of international songs and dances. When I was born, she used it for me. I grew up understanding that singing and moving in a variety of languages and rhythms was an inspiring way to connect to others.

I was a folk musician in the sixties. My degree is in journalism and anthropology, but what was really the inspiration for me was always the music of the people, so I continued to take workshops when I could with musicians from different countries. I found that African music spoke to me the most because of its accessibility. It had ways of entrée into the experience for everybody at every level. You could join in whether it was clapping or moving your body, singing in harmony or singing a melody, or playing a rhythm. It very much built a sense of strong community.

…the entire body of teachings for the children in many cultures comes through the music. It comes through being taught from the lips of an elder that you respect. The music comes into your ears and into your heart.

I took a weeklong workshop from a Congolese musician, drummer, and dancer that convinced me that rather than learning folk music from recordings, I wanted to learn from the master musicians themselves. That propelled me into my master’s degree at Wesleyan University where they offered a degree in ethnomusicology, where anthropology and music intersect. I studied with master musicians from Ghana who were in residence at Wesleyan, and they became really the most important teachers and mentors for me. Unlike some of the other ensembles that were happening at Wesleyan, the West African ensemble had this sense of life and connection outside of the classroom.

Something less academic?

Yeah, and they didn’t want us writing things down. We really didn’t do a lot of reading; we did a lot of listening and learning in the oral tradition. Through this study I came to realize that the entire body of teachings for the children in many cultures comes through the music. It comes through being taught from the lips of an elder that you respect. The music comes into your ears and into your heart. When you sit with a master or an aunt or an uncle or a parent, it reinforces this respect for the older generation that carries the tradition. In many cases, it teaches you how you’re supposed to behave, what’s important, what’s valued. That was so different from what we have in American society.

…in a traditional society the elders are teaching the children consciously. One of the main purposes of music making in a traditional culture is to inculcate in the children the mores of the society.

If you think of children’s game songs on the playground, most of them, these days, are about multiplication or learning body parts, or the alphabet, or that kind of thing: names of states, names of presidents. It isn’t the same essential teachings of how one lives within our culture.

When did that change?

I don’t even know if it ever was that way here, because the American experience was always an amalgamation of other cultures. I did a lot of playground music when I was a child. I grew up in New Rochelle, New York, in a very integrated community. We all did games that I later understood were the music of the Georgia Sea Islands: Bessie Jones and all that. [Bessie Jones was the legendary Georgia Sea Islands singer from whom came versions of such songs as “Little Johnny Brown,” “Shoo Turkey,” and “Juba,” which she published in her book, Step It Down.] We were teaching each other—children teaching children. But in a traditional society the elders are teaching the children consciously. One of the main purposes of music making in a traditional culture is to inculcate in the children the mores of the society. And I don’t know if that kind of cultural transmission through children’s music happens in American culture per se, maybe because there’s really no shared heritage.

And how much of that is being maintained to this day?

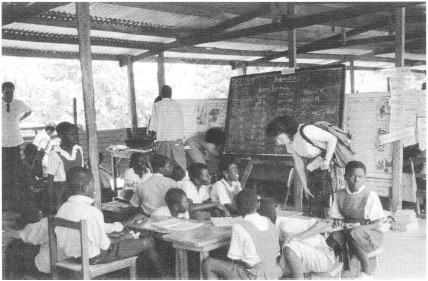

Judith visiting an open-air primary school in Ho, Ghana, in 2001, where she taught the entire school her song “Amigos”

Judith visiting an open-air primary school in Ho, Ghana, in 2001, where she taught the entire school her song “Amigos”

Well, in Ghana, a lot! When I was there in 2001, it was very exciting to see the teenagers interacting with the very young children and showing them game songs that were proverbs. The elders were sitting next to the children playing and clapping along in rhythm. They obviously took great delight in watching the teenagers teaching the six-year-olds game songs that had cultural content important to them.

Truly it takes a village to raise a child.

It really is still happening. Even though they have cars and cell phones and everything, the music is really still pervasive. It’s not being destroyed.

I’ve been doing some reading about Kenya because our school is studying Kenya this year, and the opposite seems to be true there, where the musical cultures seem to be disappearing at an alarming rate. The Maasai still hold on to their culture, but the Kikuyu don’t have much left. Much of their musical culture has been replaced by Christian gospel music and benga music.

Right. Every area has something that describes the amalgam of the old and the new. Often it’s traditional drums and rhythms with American rock ’n’ roll. Ghana has highlife and Nigeria has juju and that kind of city music.

In the cities there is probably a lot dying out, but when you get out into the village areas they’re still relatively untouched. A lot of young people major in traditional music and arts and then go into the villages and teach it. That’s the whole sankofa symbol, which is the logo on the Connecticut Folklife letterhead: that you are rooted in the past, you honor and respect the past. It gives you the foundation for the present and it gives you the tools to move into the future without forgetting where your roots were. It’s one of the most important symbols in Ghana.

In my master’s program I started doing workshops with the repertoire I was getting directly from master musicians. Teachers were really excited about the repertoire because they found it was infused with life that can only be learned from a culture bearer. They wanted to transmit that to their students, who then became excited about the music. There was no place until then to get it. So that was what pushed me into going back to college and getting my master’s: to gain expertise in music of a few particular cultures, but also, in the process, in how you learn from a master musician and how you then hold the context of that song so that when you teach it to children or teachers, you retain something of the value that the culture itself puts on that music.

After I finished my master’s, I wasn’t quite sure what to do with it. In fact, my thesis was the beginning of World Music Press. I photocopied it and went to an Orff conference [American music education conference based on the music pedagogy of German composer Carl Orff] in 1983 or 1984, carrying fifty copies, spiral bound. I sat outside the door to the exhibit and talked to people saying, “This is a collection of children’s game songs from Ghana and Zimbabwe that I learned from master musicians; are you interested in it?” And they all grabbed it. Teachers brought people to my hotel room in droves, fighting over the few copies I had left. I was selling it for $10 and called it Songs from Singing Cultures, Volume I, not knowing whether there would be a Volume II. I went home and told the story to my husband. We realized that what happened was the expression of teachers’ hunger for authentic multicultural music that they were not getting in the standard music textbook series.

They had the music but they had no cultural context. Just the notes, the songs, and the words.

And a lot of times the words were not translated accurately. If you knew the language you realized they were not giving you what the song actually meant. And you got no context; you did not get the culture bearer on a recording.

There were beautiful Western-style children’s singing voices on those textbook recordings.

You still often have that. But now they’re making more of an effort to record the culture bearers. I became an editor in 1995 for Macmillan’s total revamp, and I introduced them to the idea of including culture bearers in their recordings.

Share the Music?

Yes. But both Macmillan and Silver Burdett have licensed a lot of our songs for these revisions now, because they finally understood. This was partly the work of World Music Press proselytizing to the teachers. You know I have that checklist which is on the website [see below]. That checklist became how I evaluated everything. These were things that the big publishing companies began to embrace as World Music Press began having more of an impact on the teachers who were demanding it. So I thought, “Okay, I’m going to put all my skills together and create a publishing company that walks the line between ethnomusicology and music education.” And the culture bearers will always be the primary authors. But if they don’t function in the education arena, then we’ll pair them—if not with me, with someone who has studied their music and they know and they trust and that’ll be their translator into the education arena.

A Checklist for Evaluating Multicultural Materials

by Judith Cook Tucker

Publisher, World Music Press

Look for the following in any resource to be sure it is as authentic, accessible, and practical as possible, while at the same time it respects the integrity of the culture.

- Prepared with the involvement of a culture bearer (someone raised in the culture). In many cultures, music and other arts are an integral part of every aspect of the culture, and need to be placed in context by an insider who has the depth of knowledge necessary to increase your understanding. (Their presentation may be assisted by a student of the culture.)

- Biographical information about the contributor(s) including their personal comments about the selections.

- Each piece/work should be set in cultural context, including the source, when it is performed, by whom, circumstances etc.

- The work should include historical/geographical background, maps, specific locale (not identified only by continent or ethnic group).

- Original language with pronunciation, literal translation, interpretation of deeper meanings/layers of meaning. In this way, if a singable translation or version is included, you know how it deviates from the actual meaning.

- Photographs, illustrations (preferably by someone from the culture).

- Musical transcriptions if at all possible. (Sometimes a skeletal or simplified transcription is best, but you'd be amazed at how many songs are presented with lyrics only.)

- Companion audio recording of all material in the collection featuring native singers or their long-time students, and employing authentic instruments and arrangements. (There is no substitute for hearing the nuances and subtleties or styling and pronunciation. These cannot be written down and must be heard. In many cultures, learning music is primarily or entirely an oral/aural experience.)

- Games include directions.

- No sacred materials (ritual, holy: this does not refer to hymns or spirituals) in a collection intended for casual school/community use. It is inappropriate in many cultures to use these out of context unless the tradition is your own and you can make any necessary alterations: e.g., among the Navajo, the songs of the Blessingway, Beautyway, and Nightway chants ARE the ritual, and are not sung out of context without changes even by the Navajo. In many cultures, the singer of such songs would have spent a lifetime learning them, and would never use them casually. Use the guideline: If someone from the culture observed my group while I was teaching or performing this song, would they be offended?

Limited Copying Permission:

You may copy this checklist as a handout for workshops and music education courses.

© 1990 World Music Press/© 2009 Assigned to Plank Road Publishing, Inc. • www.musick8.com • 1-800-437-0832

Click for a printable version.

I was the first one with Let Your Voice Be Heard because I was bringing the music of Ghana and Zimbabwe into the classroom. Then I immediately tried to get the rights for Step it Down, but the University of Mississippi Press got it ahead of me. But I started to market that aggressively—the Bessie Jones work.

Then people in the ethnomusicology world started to bring me manuscripts, saying, “I’ve been publishing only scholarly work but I am Ugandan, and I have this collection of children’s songs that the Society for Ethnomusicology people aren’t interested in, but are you?” And I’d go, “Goldmine!” That was Songs and Stories from Uganda [by W. Moses Serwadda]. It was originally published by Crowell in a hardcover edition with the wonderful woodcuts by [Leo and Diane] Dillon. And we brought out the recording, which Crowell didn’t care about and hadn’t released.

…I offered my manuscript of what became Let Your Voice Be Heard to Alfred and Hal Leonard and they said, “We could publish it as a collection of songs, but we don’t really care about any of the rest of it.” I said, “But the rest of it is the most important part!”

That’s been one of the issues with printed materials: that you can sing those melodies from the page, but without the context they don’t have any life to them. They can’t be notated the way they should really be sung.

One of the reasons I even went into publishing was because I offered my manuscript of what became Let Your Voice Be Heard to Alfred and Hal Leonard and they said, “We could publish it as a collection of songs, but we don’t really care about any of the rest of it.” I said, “But the rest of it is the most important part!” They weren’t interested in the recordings of the songs at all. That was what pushed me into saying that I’d do it myself.

I started getting manuscripts from people from different cultures saying, “I have game songs; do you want them?” These were all scholars and ethnomusicologists. So first, Patricia Shehan Campbell and Phong Nguyen partnered to do From Rice Paddies and Temple Yards, which was an overview of Vietnamese music for use in elementary classrooms written by somebody from the culture. It was the first collection of its type. We did this for a whole series of cultures. Luckily Pat Shehan Campbell immediately jumped on board with all of this and saw what I was trying to do because she had studied music, particularly of Asia. So we did the same thing with the music of Cambodia, China, and Thailand. Those three came directly from her.

Andrea Schafer, who’s Polish, came up to me, again at an Orff conference, and said, “I have a whole collection of Polish songs and games and dances, are you interested?” And I said, “I’m interested if we do all the cultural context.” So she had to get in touch with all her relatives and her husband’s relatives and we did a wonderful recording with a traditional Polish band in Chicago that she knew.

Brian Burton did Moving Within the Circle. This book was the first time that Native American people were involved in a collection of Native American music that was meant for communicating that music and those traditions to children in the mass American culture.

…the hallmark of World Music Press Publications became this cultural integrity: that it’s authentic but it’s accessible. …I was trying to help keep this music alive for the next generation of people both from and not from the culture.

The Apache group signed on with great excitement, and their voices in many cases are on the recording. Over a period of twenty years, Brian, who is part Native American himself, had won their trust and respect, so they were willing to work with him.

Really the hallmark of World Music Press Publications became this cultural integrity: that it’s authentic but it’s accessible. So it’s not ethnomusicology in the sense of that dry academic stuff where often it’s on the page but you never hear it. I was trying to help keep this music alive for the next generation of people both from and not from the culture. Many times families were buying these resources as a way of retaining their culture for their next generation of young people. That began to happen a lot. Families who had adopted children from some of these cultures were buying the book sets. Teachers who want to tie into the social studies curriculum now have something authentic to use.

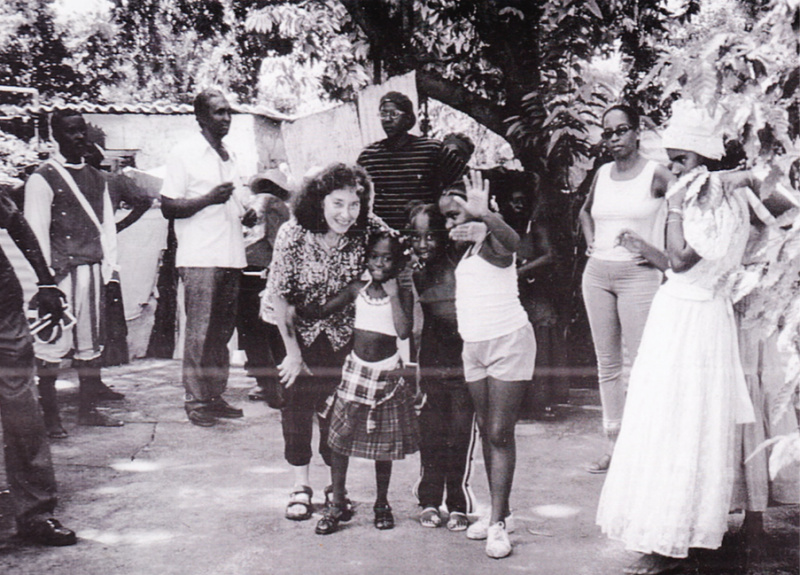

Judith visiting a traditional dance group in the city of Matanzas in Cuba while studying the vestiges of West African music in Cuban communities in 2002.

(screenshot of cover photo, issue #55/56)

Judith visiting a traditional dance group in the city of Matanzas in Cuba while studying the vestiges of West African music in Cuban communities in 2002.

(screenshot of cover photo, issue #55/56)

What seems to have happened over the years is that a lot of culturally based community centers which offered after-school programs for kids were using our publications as the foundation for their classes. So it became a way that the culture here was able to communicate their own traditions effectively.

So World Music Press started in 1985, and it’s still going in 2006, but my involvement now is very minimal. I found that it was really draining on me to do what I had to do to make the publishing company successful. My focus was being forced to change from helping to keep the repertoire alive to helping to keep the company going—meeting the bills, being able to pay for the new print run, being able to pay for storage in a warehouse, being able to pay for fulfillment of the orders where somebody calls in and there were people who were packing up the orders. That all cost me something and it meant that I had to become more of the business person than the editor-in-chief working with somebody from the culture on developing manuscripts.

And you were both of those things.

I was, and I was also the chief marketing person. I would do workshops all over the country and in Canada. By the time I got home I would take to my bed and stay in pajamas for a day. I also had health, personal, and family issues at times. With the set-up and take-down time at conferences and the whole business side of it, even though I was good at it, it became all-consuming and draining. After a while I said, “What am I doing here?”

Did you have employees?

I had a couple of part-time employees in a bookkeeping capacity and packing orders in my old house, but really it was me. Gradually I realized that my work had become the business. But what I loved was working with the material. Then I started to find even that was too draining. I’m fifty-nine and I just had that feeling that what I wanted to be doing is interacting with the people from these cultures and helping the new generation value what these immigrants, who came in their diaspora, had brought with them, whether it was Vietnamese or Cambodian immigrants who had survived Pol Pot, or the Lebanese, or now we have this vibrant Brazilian community here in Danbury. Every wave of immigration includes people who came here having been master musicians, carvers, dancers, storytellers, costume makers, chefs, puppeteers. They are all here.

Why wouldn’t they keep their traditions here? Well, because they couldn’t make a living doing it, unlike in their own traditional culture where often they were supported for being the master artists they were and had apprentices. When they came here, they really had to figure out how to make a living in the American milieu. For them, often it was working as a chef, going back to school, depending on what country they were from. Often Indian musicians could maintain a part-time profession as a teacher, like Jayanti Seshan, who’s the director of the Apsaras Dance Company. But she’s a math teacher at a middle school here.

Everybody had to do something to support their families. Gradually the kids would say. “I want to be American.” What I found here was that the children of the first and second generation of any culture didn’t really have the connection to their cultural heritage unless they went to a cultural school. But not every culture in every community created these cultural schools for them. So I began to worry on their behalf that stuff was going to die out, because I was seeing it in my own family. I don’t speak Yiddish. I’m sorry I didn’t learn it and that whole repertoire of Yiddish songs. I don’t know my own culture, and my mother’s dead now so I can’t learn it directly from her. So, in 2004, I decided that rather than spend all my energy on World Music Press, I was inspired to work more with the culture bearers in the community of the greater Danbury area where I live. I wanted to let them know that they were valued for what they had brought here to this country. I felt compelled to document what they had to offer, to preserve it and present it.

So I created the Connecticut Folklife Project with a couple of my friends who understood what I was trying to do, including Rick Asselta, who has worked closely with Jane Goodall for many years, and with the alternate high school where there are a lot of immigrant kids, and Dennis Waring, who’s an ethnomusicologist I knew from graduate school and who’s also a member of Sirius Coyote. Through the National Folk Alliance Project of Music and Dance we got the 501(c)(3) nonprofit tax-exempt status and started to get grants. What I saw were two initiatives: one was finding who these people are who live in our community, and the other was preserving those traditions. Lynn Williamson at the Institute for Community Research in Hartford had already begun doing this kind of research in her work.

I never even heard of that Institute for Community Research.

I also wanted to bring the awareness that there’s no immigrant “problem” here. There’s an immigrant treasure trove that we have in our community. Let’s find out what their traditions are, let’s appreciate them, let’s witness them, let’s acknowledge them, let’s respect and celebrate them.

ICR. Lynn’s a wonderful folklorist, a wonderful resource, and has discovered many, many people in their pocket communities retaining their traditions. She has created a program so that they will be apprenticed with somebody either from their culture or not, but who values what they have to bring. She gets grant money for that and she helps present showcases so that community organizations will find out about them.

My focus, as a musician rather than as a folklorist, was more on helping to breathe life into the artistic expressions of these people and presenting those to the community at large as a way of valuing the ethnicity of the people who are immigrants here. I also wanted to bring the awareness that there’s no immigrant “problem” here. There’s an immigrant treasure trove that we have in our community. Let’s find out what their traditions are, let’s appreciate them, let’s witness them, let’s acknowledge them, let’s respect and celebrate them.

So there are two main initiatives Connecticut Folklife has: the first is to locate, document, and preserve master artists from all different traditions. The second is to present them. So far we have hosted a series of events where we have master artists from the presented culture. We had a wonderful tabla player who performed with one of his teenaged students. The Indian community decorated the concert hall with their artwork and brought in statues, and we had donations of food for a traditional food buffet of snacks and sweets. The audience was able to witness dance and music with the Indian community. It was a wonderful celebration of Indian culture. The Indian community does this a lot for themselves, and the public is welcome. But the majority of people who come to these things for any of the ethnic celebrations tend to be the people from the culture. My goal was to have that be one third of the audience and two thirds be the rest of the community of all the other cultures, not just those who stereotypically might have an interest in other cultures. Lynn Williamson told me they’d tried that kind of thing, and what they found was that the people from the culture support us, but the other people are few and far between. I told her I didn’t think it would be true in Danbury. I think Danbury is going to be a place where they’re going to turn out in force.

Have you been right?

I’ve been right! Our last concert was the Russian folkloric youth dancers [Rossijanochka Folkloric Youth Dancers] from St. Petersburg, Russia, and probably one-third of the audience was either Russian expats or families who had adopted Russian children and wanted them to know something of their roots and wanted them to speak Russian with the dancers. The rest of the audience was the Indian community, the African-American community, the Filipino, Jewish...

Oh really? Now, is that because they’re part of your organization, because they know you? Is it through their connection with you?

It’s not so much that they’re part of the organization. It’s the intensity of my outreach to those communities. I vowed with the very first concert that we did a couple of years ago that I was going to go into the communities and pull people out and say, “You’ve got to come to this. You’re going to love it and it’s going to be interesting and exciting. Please come and network in your community and bring some people.”

Even though it’s not from their community. So you’d go into the Indian community, and tell them to go to the African concert....

Right. And it worked. The newspaper covered it. And I would be quoted saying, “This is a celebration of our diverse community.” In the greater Danbury community, fifty-five languages are spoken in our schools. It just seemed like having a series like this that celebrated each of the cultures was an important way to acknowledge them to each other and to the community as a whole.

And about how big is an audience for these concerts?

650.

Wow!

And very diverse. And very diverse age-wise, which is also a goal of mine. We had so many children at this last concert. During the intermission, flocks of children went up on the stage and pretended they were the Russian youth dancers, who were children themselves.

And did they come because of outreach to schools?

I saturated the schools with fliers. I talked to the music teachers and the superintendent of music and art, who’s very supportive here. But I also found pockets, like the families who have adopted Russian children, and they spread the word. I went to the Russian Orthodox, the Greek Orthodox, and the Ukrainian churches and they spread the word. Fourteen families from Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Church came. I invited a business that does all European arts and crafts, and she created a wonderful display. They thronged to her booth. That was typical.

This is one of the issues that comes up with most white activist types of organizations and in CMN: how do we get people to come to us? And I have said for years, “You can’t ask people to come to you, you have to go to them,” and this is exactly what you’ve been doing.

Yes. But let me tell you something. There’s an important book you ought to read. Donna Walker-Kuhne is my guru in community outreach through the arts. She wrote a book called Invitation to the Party, which I have read a million times. It teaches how to issue that “invitation” without being the white or the black person who says, “I want to help you do something here.” The issue is not what you’re bringing to them: it’s what they are going to bring to you. But the invitation to the party has to be issued in a way that they genuinely feel that you want them to give you what they have to offer. In all of our PR, we issue an invitation to our party with the message that we want them there for what they have to offer.

Walker-Kuhne began her outreach to the Native American center across the street from the Public Theater [in New York City], where she worked. She went across the street to introduce herself when she was brought onboard to do audience development. (That’s officially what it’s called, but it’s really building community.) She asked the people at the American Indian Community House if they had ever been to programs at the Public Theater. And they said, “No.” She asked, “Why not?” They said, “No one ever asked us. You’re the first person who’s come across the street. And so we thought it wasn’t anything that we were welcomed to.” And she said, “What else?” They said, “We wouldn’t have known what to wear. We wouldn’t have known how to behave. We wouldn’t have known what’s appropriate, so we didn’t come.” And she said, “We want you! Wear what you want to wear; it’s informal. We welcome you; our door is open. Please, we need what you have to offer.” And she did this with many, many communities, where she would say, “How can we serve you better?” It was a heartfelt statement of wanting to share each other’s gifts.

We have applied this thinking to our programs. It means that when the Russian dancers did a dance workshop for dancers in our community, the Indian dance teacher and some of her students came. She vowed that she would be there for me to be part of this Russian thing, specifically so that the Russian students would get something from the Indian dance students of their age and her Indian dance students would learn something from the Russians. She came to the concert bringing a lot of people with her from the Indian community. They came over to me saying, “You are doing something so wonderful!” This was at the Russian concert: this wasn’t at the Indian concert. They were there, too, but of course there they were feeling very wonderful that we were celebrating them. They suggested the idea of an Asian Day festival with all the different Indian dancers and taiko drumming [traditional Japanese drumming] and a Chinese dancer. They knew some of these people and promised to convince them to take part. You begin to have this revitalization of that sense that we are all here building the community together and we value each other and we’re going to work together and we’re going to become tight as a community and we will make an effort to go, even though it’s not our culture, and celebrate what’s on the stage as an expression of the cultures of our area.

And then you have ownership of the bigger American community as opposed to “my Indian community.”

That’s right. Our American community embodies all this. Why aren’t we saying we need to be there at the Lebanese festival as Indians in our community, not because we’re Indian but because we’re part of the Danbury community, and so are they, and we want to show them we care. It’s not only the Lebanese community that values the Lebanese dancing, food, and storytelling. We care, too.

So how do you bring this into a school setting and really empower the children from a bunch of different cultures, as well as the children from outside the culture, to feel comfortable with it?

“Is it appropriate for me to do something from Ghana?” Well, a Ghanaian is going to say, “If you do this with a good heart and you have tried to master it by listening to a culture bearer, you are doing good work!”

I think the clue to everything is context and familiarity. If you’re having a multicultural festival, as we do here in almost every school, then you have that sense of having something that is valued by the school system as a whole. If you have a school system where it’s mostly one culture (not necessarily all white), how do you introduce the idea of valuing other cultures? I think it’s just picking and choosing repertoire that is exciting for anybody to do and introducing it in a cultural context. The teacher is the most important part of the whole thing. Their whole attitude toward the material, their enthusiasm and passion for it, and the amount of knowledge that they bring to the study is key. They must be able to speak in children’s terms about cultural context and make it come alive for all the kids. The teacher needs to know how to connect the “new” culture to the familiar one through a game song from the tradition that’s the majority population, for example. If you have an African-American classroom, do one of the game songs they already know. Then you show them a map and say, “Kids in another part of the world do games songs, too. Here’s one of theirs.” If they want to laugh at the way the language sounds at first, that’s because it tickles their ears. You can giggle because it’s new and different, but what you really are going to do is be excited by it. And that laughter is maybe a beginning entrée of excitement.

If you have made that effort to be a serious student of that tradition in some small way, then if somebody from that culture walked in from their culture, they would be delighted.

I always go back to context, which empowers the teacher to feel that they have the tools to personalize it, to make it come alive for the classroom and then to communicate it to the children. The teacher begins to be the conduit for the life force of that offering to flow to the children. So if you have a teacher who says they’re not comfortable with this, and wonders, “Is it appropriate—I’m Jewish, I grew up in the Bronx—is it appropriate for me to do something from Ghana?” Well, a Ghanaian is going to say, “If you do this with a good heart and you have tried to master it by listening to a culture bearer, you are doing good work!” which is why World Music Press has culture bearers pronouncing everything. If you have made that effort to be a serious student of that tradition in some small way, then if somebody from that culture walked in from their culture, they would be delighted. The way they’re going to be delighted depends on your attitude, your heart, your trying to be authentic, your acknowledgement that this is something important that you want to share and that you are a student of the culture.

So it might not be perfect, but you don’t want students to miss out by not having it at all. Choose your repertoire carefully and limit it to things that won’t be harmed. For example you don’t want to do something sacred, like a Navajo Blessingway song. The Navajo shaman took his entire life to do it accurately; that’s who should be doing it. But a Navajo children’s game or a corn grinding song or a social dance song, everybody welcomes you doing that if you do it with the acknowledgment of the respect for the culture and the right mindset. Present the music in context, with passion, accuracy, and authenticity as much as you can, learned from a culture bearer if you can, or from a resource that involves the culture bearers, if you can. Then, if a student in that classroom from that culture perks up and you see that they would like to volunteer, you could say, “I think maybe my pronunciation isn’t perfect, could you help me?” And if they want to they will, and if they don’t, they won’t, and let it drop. Or you say, “Can I meet with your parents or your grandparents? I’d love to learn how to sing this better so I can share it better with your friends.” You could ask yourself, “If somebody from that culture came into my classroom and witnessed this, would they cry tears of delight?” You want to be able to say, “Yes!” And most often they will.

When I went to Ghana, it was the same thing. They didn’t care if we were white or black, old or young. But they loved the fact that we were there valuing what they could teach us. That was a valuable lesson for us to come home with. To teach this material, we just had to have a big heart and love what they were teaching us. This holds true even in a classroom where you’re trying to bring this material to the students. Having the students feel like this is an open invitation to something exciting, new, and wonderful. This whole world of cultural richness is about to be given to them with the knowledge of the world beyond their own doorstep. That’s what’s exciting to me.

World Music Press is now part of Music K-8.

Originally published in Issue #55/56, Winter/Spring 2007.