Culture, Connection, & the Magic of Music

An Interview With José-Luis Orozco

by Bonnie Lockhart

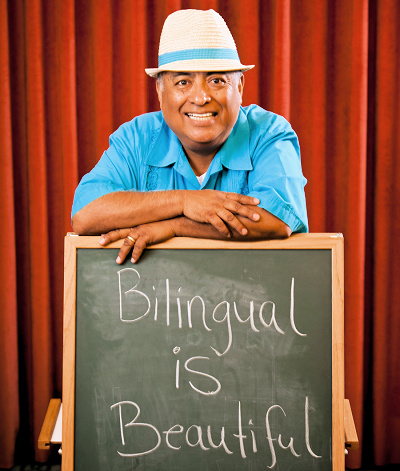

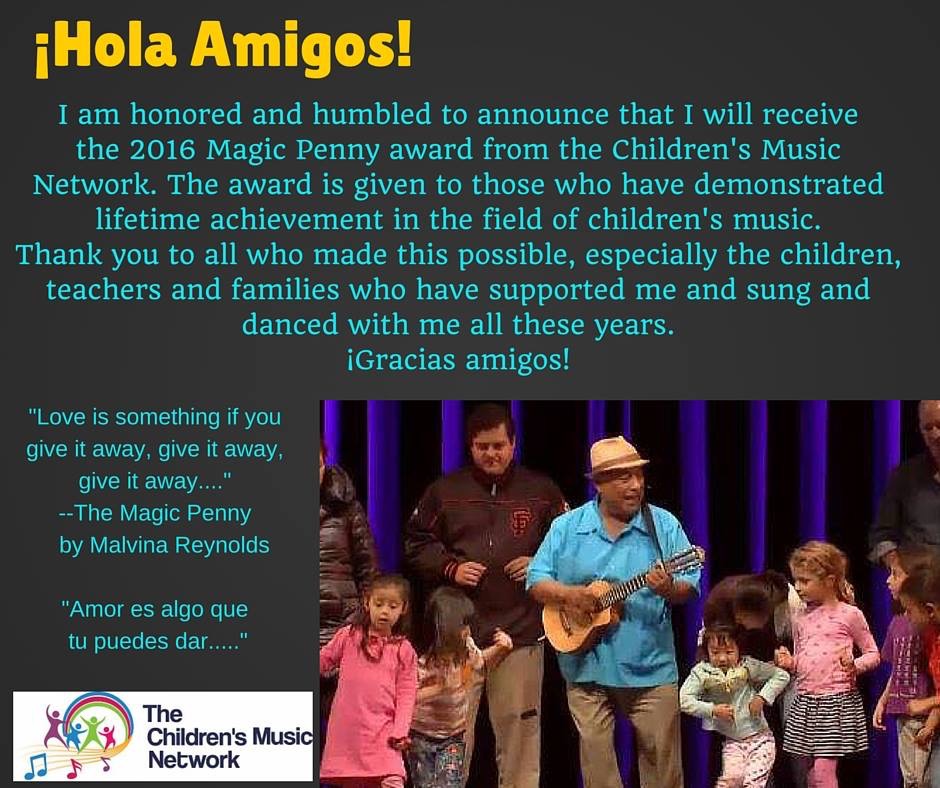

José-Luis Orozco is the 2016 recipient of CMN’s Magic Penny Award. He is a bilingual singer, songwriter, and educator, as well as a collector of Spanish language children’s music, recording artist, and creator of three songbooks for children. A longtime CMN member and past board member, José-Luis celebrated forty-six fruitful years of sharing bilingual children’s music in 2013. He’s been the recipient of dozens of prestigious awards and has been recognized by the Congressional Hispanic Caucus in Washington, DC, the California Latino Legislative Caucus, and most recently, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, who honored him with their Lifetime Achievement in the Arts Award. He has been invited three times to the White House, most recently on March 28, 2016 at the White House Easter Egg Roll. But he’s not resting on these impressive laurels. José-Luis continues to tour, bringing his lively, participatory concerts and workshops to over 100,000 teachers and

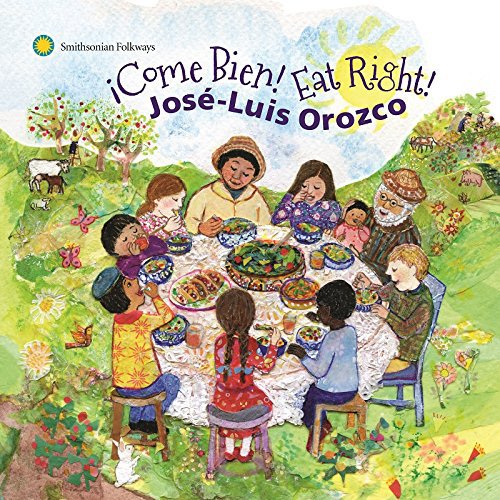

caregivers each year at conferences throughout the country. He has now shared his songs with two generations of teachers who, in turn, have shared them with countless delighted children. His most recent recording, ¡Come Bien! Eat Right! was nominated for a Grammy this year. Smithsonian Folkways, on whose label the CD is recorded, describes it as “an enlightening, engaging, and fun-filled approach to making music for the good of all.”

José-Luis was an early innovator in the field of bilingual (now becoming known as dual language) education. His childhood experience of touring the world with the Mexico City Boys Choir, his master’s degree in multicultural education and experience as vice chancellor of National Hispanic University, his warm and powerful voice, and his fun-loving nature gave him a unique set of skills to put music on the map of multicultural curriculum development from the very start.

José-Luis has lived in Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, and is currently living in Santa Cruz. He’s the father of four and grandfather of two. His oldest son, José-Luis, is his agent and manager.

When we spoke, José-Luis had just returned home from a road trip including performances in Flint, Michigan, and Lake Tahoe in California.

To find out more about José-Luis’s work, read Phil Hoose’s 1996 interview in the Fall 1996 issue of PIO! found in the members section of the CMN website.

Bonnie: Let’s start with a question about who sang to you when you were a kid.

José-Luis: It was mainly my mother and my grandmother in Mexico City where I was born. And then my father played the violin, so there was music around the house. I became a member of the Mexico City Boys Choir at age seven, and traveled the Mexican republic. By age ten I had gone to every single state of the republic. At age ten I was selected to be a member of the choir that traveled for three years, three full years without going back to Mexico City. We visited thirty-four countries, performing in major concert halls of Central and South America, the Caribbean, and Europe. So that was part of a strong foundation for the career that I have as an educator, a musician, a songwriter, and performer.

What was that like—being a really young person and being on the road so much?

Well, I’ve been on the road all my life!

Yes, you started young!

Yes. When I was seven I started studying music in Mexico City and then I came to the United States in 1970.

Español

Español

What brought you to the United States?

I came because I was a student in Mexico; I lived very close to where the student massacre of Tlatelolco happened. Actually, Tlatelolco was a place where I was baptized and it is a very important place in Mexican history. It was the big marketplace of the Aztecs where they traded all the goods with the people from the rest of the country. After the Spanish conquered the Aztecs, they built a church there: Santiago Tlatelolco, for Santiago, the patron saint of Spain. In English we call him Saint James. That’s where I was baptized. And then, that’s where the massacre of Tlatelolco happened in 1968.

The massacre—there were student uprisings all over the world—I’m sure that must have affected you quite personally.

It did. I lived very close to where it happened, about eight blocks. But the thing is, I worked in the evenings as a cashier and I went to school during the day. Actually, I was going to go to that [student] rally, but I saw the police, I saw the army, and I decided to go to work. That was the only rally I was going to participate in, because the rest of the marches happened by the University and other parts of the city. I didn’t have time; I had to work to help my mother because we were a family of ten. My older brother and I were the ones helping my mother to sustain our household.

English

English

And where are you in the lineup of those ten?

I was the second one. My older brother also became a member of the choir. He didn’t travel with me, though. He was older than me and his voice was changing, so that’s why he was not selected. And he became a doctor. Now he’s a retired doctor in Mexico. My brothers and sisters, many of them became teachers and architects. I’m the one who’s continued in the field of music all my life.

I decided to leave Mexico in 1970. After the massacre, one of my classmates came to California. He wrote to me; he told me how good things were here, for schools, for jobs. That was one of the reasons I came. I was looking for better opportunities, and I found the golden opportunity: I was able to go to the University of California at Berkeley. I graduated and then I got a master’s degree in multicultural education. I’ve been working in the field of education and music ever since.

You have a formidable background as an educator, as a founder of the National Hispanic University, centrally involved in the early 1970s development of bilingual and multicultural education. How did that evolve?

It started really early. As soon as I got off the bus—I didn’t come by plane, I came by bus. And two days after I arrived in San Jose—I lived in San Jose for a year—I was invited by several friends to visit some of the high schools and their Spanish classes in Los Altos, San Jose, Oakland, and Berkeley. They told me, “We need somebody like you to teach and to talk about the culture and the history and whatever else you learned as a child with your travels throughout the different cultures and countries.” They said, “There is a great opportunity for you here with the skills that you already have.” I was hired by the Berkeley Unified School District. Berkeley was part of a consortium of five California school districts: Berkeley, Richmond, Oakland, Daly City, and Union City. The consortium gave me two jobs: one, to be a community liaison to the bilingual program, and the other, to teach music to the children, to the teachers, and to the parents. This was at the end of 1970.

That relationship with the consortium evolved out of singing in classrooms?

Yes. The head of the bilingual consortium was in Berkeley, but I was working in the five school districts, so it all started there. There was a need to create materials to promote the traditions, so I started recording and giving workshops. Many, many school districts used to come to Berkeley. We had a media center; it was like a laboratory. People would visit the bilingual classes we had at Thousand Oaks, at Columbus, now Rosa Parks [Berkeley public elementary schools], and Franklin Parent Nursery. The consortium was at the very beginning of the bilingual programs. And through that, we got the connection with the network of bilingual programs in the state of California, with the different school districts, and then with the rest of the country—the public schools, universities, and later on the public libraries. That has been my network. It started with that bilingual program in Berkeley. And the need that still exists today, to promote diversity. You and I and the Children’s Music

Network are always promoting diversity and using music as a tool to teach anything that we can teach.

You really got in on the ground floor. And now, here we are. There’s been good news and bad news in the world of bilingual education. I’d be interested to hear about what you, and the whole movement, are really proud of having achieved and what obstacles have been thrown at you.

We go through a roller coaster—could be politics, could be economics, could be education. I am very proud to say that I have gone through all of that, and music has been very strong in sustaining me in many ways: first through the recordings, then with the publications of my books with major publishers like Scholastic and Dutton and licensing with other publishers. Bilingual education is very political. Now with the changing demographic, it looks very promising everywhere. It’s now called dual language. I visit many, many states, and there is now great acceptance of the dual language programs, and it’s a movement that is growing. It’s all political. Some people, once they realized that it really works, wanted to do it. But for many, it was unaccepted because they wouldn’t understand exactly what the process was for being bilingual. Sometimes the ones who were in power went against bilingual education, but they would send their own kids to foreign countries to learn the language and

live the culture. But they didn’t want it at home. And now they realize that it is cheaper also for them. They want their kids in dual language programs and don’t need to spend that money in sending them abroad [chuckles]! I don’t want to get too much into politics, but music has kept me alive and happy for all these years.

That certainly shows! Let’s talk about your books, De Colores, and the fifteen others that came after that. They’re so wonderful! How did the collaboration with the illustrator come about, and what motivated you to put out that first book? Did you know it was the first of many, or was it just that one thing led to another?

The first ones were homemade songbooks, and actually, I used some of the material from my work as handouts. Then, through some friends and connections, and through people at the many conferences, publishers saw how successful my work was. That’s how De Colores was created. I didn’t even know the illustrator, Elisa Kleven, who lived in Albany [a town next to Berkeley], but we met in New York. So the publishers said, “We like your work, and we found this great illustrator. She lives close to where you are and we just published a book by her. The title is Abuela, and we’re going to send you some of the illustrations and if you like her….” It was just great! So we met, and she has illustrated three of my books.

Thanks for making them! They’re such valuable resources for those of us who are singing these songs with kids. What about recording? I know you said it started out of wanting to have recordings to give to teachers and educators who were developing bilingual education as they went along. How did you start your own recording company? Was that, in fact, the first way you started recording?

It came at the time when there were attacks on bilingual education and funds were being cut. We had started the National Hispanic University, first in Berkeley then in Oakland. It’s now in San Jose. And then it was a rough road. It was nice, a good experience. But that’s when I decided that probably I was going to be happier just doing my music. Because even when I was the vice chancellor of the University, a teacher trainer, I still was receiving a lot of calls. There was a high demand for my work, not only in the schools but also in the public libraries, the universities, and giving concerts here and there. So that’s how I started my own label—Arco Iris Records, which means Rainbow Records. It’s been in existence since 1984, a long time.

That’s a long survival for this kind of project. Was your distribution for that mainly through bilingual education networks?

It was education networks in general. A lot of outlets were calling and wanted me to send out my recordings. From a little cassette, we moved on to LPs. I produced, I think, four LP records. And then again came the cassettes, and then the CDs. I have about ten different recordings. The last one, ¡Come Bien! Eat Right! was a collaboration with Smithsonian Folkways Records. And that’s the one that was nominated for the 2015 Grammy Award this February.

How did that relationship with Smithsonian Folkways form?

I’ve collaborated with the Smithsonian on different events that they’ve had in Washington. We came up, together, with this idea of a recording on nutrition, because there is a big epidemic all over the world about obesity, diabetes, heart diseases, and the problem that we have now with food. The food we eat now is not the same food we used to eat thirty years ago, or fifty years ago. So that’s how it came about.

With music, we can teach anything. We can teach the basic skills—colors, numbers, letters, body parts, nature, and then, save the earth, everything! And this topic was important to me because of the Latino communities. You know, it’s sad to say, my country, Mexico, is number one in obesity and diabetes. I visited many communities in the country and I saw how the diet is not working for everybody. It’s important to give them little messages, games to solve, tongue twisters, dances, and that’s what I created. I created probably ninety-five percent of the material. The work was done also in collaboration with the band Quetzal. Quetzal [Flores] is the director; the name of his band is Quetzal. They won a Grammy three years ago. They’ve been in the field of music—folk music and political music—for the past twenty or twenty-five years. Quetzal is also the national bird of Guatemala, but [Quetzal Flores] was born and raised in California. We’ve been performing everywhere and promoting the

recording and giving the message to the communities.

Have there ever been any conflicts between the two interests and commitments of yours? Being a professional musician and touring artist, and being an educator and advocate for bilingual education?

No, and I would emphasize here it’s not only bilingual education—it’s multicultural. I have not really encountered conflicts because music is a friendly tool; it’s a very friendly tool. People want to hear rhythms from other countries, you know, even in Spanish, if they have Spanish-speaking kids. And now, every single state in the country has Spanish-speaking people. I have even been to Alaska, where they also have dual language programs. And there are private schools that have French/English, German/English. But I would emphasize the multiculturalism part, the diversity that you and I and many others promote all the time because we want children to grow up in peaceful communities. If they learn from each other at an early age about other languages and other cultures and how to respect each other, obviously when they grow up, they don’t have any big problems of discrimination.

That’s central to what you do, and it comes out so well in the work that you do and the songs that you’ve written. You started writing your own material early in your career. How did that feel when you were first adding in your original songs to the traditional materials?

As a child I was singing and I was singing all over the world. We were performing songs that we already knew in English, in French, in Latin, in German, in Spanish. And then, we lived with families most of the time. We had stories to tell; they wanted to hear about our trips, about Mexico, and we wanted to hear about their families. We had stories and songs and jokes, so as we traveled we tried to make our own songs. And then when I started working here in the United States, there was a great need for more music for the Spanish-speaking kids. I already had the songs and games that I learned as a child in my barrio, and then the ones that I learned with the children’s choir. There was a need and people asked, “Where can we get this information?” And can you write something about body parts, something for greetings? Can you write something about—?” you know, different things that they wanted. That’s how I started recording part of the traditions and started making my own songs. And some

of them were adaptations, too. Others were translations of well-known songs, like “Eensy Weensy Spider” and “This Land is Your Land” and “Old MacDonald,” songs like that. And I was starting to translate some of the songs from Spanish to English, like “Los Pollitos.” It evolves; there’s a demand, and it’s a motivator. And even today there is always something you want to teach.

When did you become aware of other people that were doing the same kind of education, community building, and validation of cultures through music with young children? Did they come into your view fairly early in your work?

I think so. Our great teachers—like Malvina Reynolds, Ella Jenkins, Pete Seeger, and many others—for me, those are my role models. It was at La Peña [Cultural Center] that I met Malvina. And then with Ella Jenkins; she spent some time in the Bay Area. She was at San Francisco State; that’s how I met her. With Pete Seeger, the same thing, through La Peña. And in the late eighties, I was invited to be a board member of Sing Out! Magazine, so I saw him more. And even before that [I knew about him] through his recordings I saw in second hand stores on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley. Pete Seeger was very well known and people told me, “This is a good guy, you should learn some of his songs.” And then came Woody Guthrie as part of that. And I was always doing research. I was very lucky to meet the three of them: Malvina Reynolds in Berkeley, Ella Jenkins in San Francisco, and then Pete Seeger in different places. He invited me to go to the Hudson River, the Clearwater Festival, two summers in the eighties.

All fellow Magic Penny awardees—good company! It can be a kind of lonely, difficult career, being a solo artist. What sustained you in your early days, and what continues to sustain you at this point?

In terms of work, of income, it was mainly working in the schools, the universities, doing the teacher trainings and giving the talks about Latin American music, the traditions, promoting literacy and all the skills that I got with my master’s in multicultural education, and mainly using music as a tool.

But being a solo artist, it is not hard actually. When I travel, sometimes people travel with me. In terms of performing, I have performed with the Plum City Players [the song and story trio of CMN members Annie Hershey, Bonnie Lockhart, and Nancy Schimmel, who performed around the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1980s and 1990s]. I don’t know if you remember the incident—La Peña had given me a date [to perform]. I had been active with La Peña from the day they opened—I was a member of the cultural committee. So when I was doing the children’s concerts, they gave me a Saturday. And then Annie calls me from the Plum City Players and she says, “We want to talk to you because La Peña gave you a date, and they also gave us the same date! I wonder if you want to share the morning with us.” I said, “Of course!” [laughs], and that was the beginning of doing some things with all of you. And I was a member of the Freedom Song Network for a while; it was fun, too.

You’re a wonderful singer, songwriter, and educator, but to me, one of your great gifts is as a song leader. You have a very beautiful voice, but it never makes people feel like, “Oh, he’s a real singer and I shouldn’t sing along.” I think that can happen to people. You just absolutely get everybody feeling like, “Hey! We’re going to just sing it out!” I wonder if that’s just something that came naturally, or if that’s a value that you experienced in other people’s presentations? It’s something very dear to the hearts of lots of people in CMN, that ability to get people singing. I wonder how you came to that.

I think it came from the time I was a child, singing with the choir and then singing for other people. And then here, I remember going to Faith Petric’s place in San Francisco [gatherings of the San Francisco Folk Music Club and of the Freedom Song Network], a great place to share music. Music is a friendly tool, and the person sharing a song should be friendly, too [chuckles]. That’s one of the ways, you know? I remember Jon Fromer, how friendly he was, inviting everybody to join and sing, and Faith Petric the same thing, and many, many people. That’s the way to motivate people and get them involved and to open up more, and then later on they also become singers and some become writers. I think that’s what it’s all about.

I wonder about the experience you had as a child. Do you have any vivid memories of the adult leaders—choir teachers and directors? What was that relationship with those people who brought you into the world of music?

The first ones were my grandmother, my mother, and my father, and then, the director of the choir. He actually didn’t have too much experience in music. But he was surrounded by people who were good musicians, people who had studied music, choral music. Actually the director of the first part of the tour was only twenty-one years old. He had been a member of the children’s choir. He had traveled the world, too. It was a great experience. Obviously we identified with him, and he identified with us because he had been part of the choir as a child. And we met people from other choirs—in Argentina, in Paris. We exchanged ideas. The music was always great; we all got along okay, there was no problem. Living with families was also very good. Most of the time they belonged to some kind of association, some kind of club like the Rotary Club, or Lions Club. Some of them were from Catholic organizations. You know Mexico is—or was—a Catholic country. Still is, I think. We all were Catholics, and

they always welcomed us. Living with adults and their kids, it was always fun.

Have you been able to keep in touch with any of those kids from the choir?

Yes, and they continue to sing the songs they knew as children. When I visit, I join them. Some of them are dying, which is sad, but the ones that are left are still singing—fifteen or sixteen of them. And it is nice to see that. I always call them when I go to Mexico.

You’ve had a long, and continually growing, career. Do you have any advice for people who are just starting out?

My advice is to just keep on doing what they like to do. There is an open field with music, because music is everything. We have music from the time we are born to the time we die. We have the lullabies when we are born. They sing the nice songs for us to be happy. And when we leave this world, there are so many songs that people sing when people depart. In Spanish there’s “De Colores” and “Las Mañanitas.” It’s important to continue to give children music. In many places, the budgets for the arts have been cut, and it is important to keep the music going. And that’s what I have been doing. I still have been able to survive and go to schools and libraries. Also, when I go to universities, I talk to student teachers, to the ones that have been doing music. Keep doing what you like. In my case, it’s promoting diversity and trying to find new projects. You can do anything with music—music about the environment, music about friendship, music for peace, music for respecting each other,

music to teach history, to teach culture, to keep up the good work! If you are already doing that, keep on doing it and share it with the rest of the world.

Many times, there’s a magic that happens when everything connects. Do you have any thoughts on what the difference is between a good and a magical performance?

I always try to give what I have with love. My presentations are interactive. It’s not only that we want the children to listen, but also to do something: hand motions, body motions, and sing-along songs are really important. In some places, you do get a great, magic response. Other times…I don’t know. Many of the times, most of the kids respond. Since you and I have been doing this for so many years, we know what works and what doesn’t work [laughs]. We have to give them what works, and what makes them happy, and what makes them learn something. That’s the important part as a communicator with music and education.

Magic moments…. This one is not related to children only. I was with Dolores Huerta—this is very magic—at the monument of Mother Jones at Mount Olive. Dolores was invited to speak by the University of Illinois in Springfield. I was also invited to sing some songs, including “The Ballad of Dolores Huerta.” So we had a dinner at the University. She gave a speech, and I sang the songs that I had to sing. And then the next day, we go to Mount Olive, about an hour and a half south of Springfield. There is this huge, beautiful monument of Mother Jones. It’s overcast. It’s sprinkling a little bit, and Dolores Huerta is giving her speech and the clouds are there, and the water is just coming down. She finishes, and she says, “Oh, look, the guitar is getting wet.” I said, “Yeah, don’t worry, we’re going to sing something good to get everybody happy here.” So I asked everybody, “You know, the clouds are here, it’s raining a little bit, but let’s sing ‘This Little Light of Mine.’ Let’s put our

voices together and see what happens. You know, maybe the rain goes away.” And we are singing “This Little Light of Mine,” and the clouds move away, and the sun starts shinning on all of us. That’s magic! And Dolores Huerta, any time we are together, in any place, she always tells this story. But the other important thing, this lady from the audience comes—she was probably the oldest in the group of 200 to 250 people—and then she comes and talks to us, and she says, “I really want to thank you. My son was a union activist. He also supported the UFW [United Farm Workers] from here and he died in the mine in an accident, and I was waiting for a message from him. I was waiting for a message from him, and I think this is the message. It’s the message of the light coming to all of us.” So she came to thank us for that. More than magic, it’s just incredible! I don’t know if it was the song or the voices, but it happened. And we were singing “This Little Light of Mine.” We all were singing,

actually, and clapping.

The other magic of the music is when parents come and talk to me, and say, “You know, my little daughter or my little son doesn’t speak Spanish even though we speak Spanish all the time and the grandparents speak Spanish. But with your music, they learn Spanish.” Or even in the classroom, some kids that don’t talk at all, and don’t sing at all, and don’t get involved at all, the teachers tell me, “When we play your music, the kids are singing, they start singing.” And those are great rewards. If there is that impact of our work out there, that means that it’s very rewarding. It’s a nice feeling. It’s motivating to keep on doing it.

Is there anything else you’d like to tell us?

Obviously, I’m much honored to receive the Magic Penny Award, named after a song by Malvina Reynolds, somebody that I respect very much. And from the Children’s Music Network: a great organization of people that are out there, doing their best with music, doing outreach everywhere in the country and also abroad. Thanks to you and everybody. We will be celebrating in October all together!