In Part I of this article, Lisa examines the roots of racism in music education and how white educators can face up to their cultural biases. Part II invites readers to consider ways of working toward culturally responsive teaching. —Ed.

A Bridge Over Troubled Water

One thing I have learned in doing research on anti-racism is that educators (myself included) fall prey to many “multicultural” songs and stories that are attributed to a long-ago tribe or ancient storyteller. The intention is good—to incorporate the words and music of different cultures in the interest of creating diversity—but the impact may not be helpful. Misattributing a song, image, or quote can lead to further misunderstanding and even mistrust.

My recent lesson in this area is never take any quotes or proverbs at face value. Just as in the game of Telephone, the words, meaning, and often even the author get lost in the ether, resulting in misrepresentation of a person or culture. It is vital to do our best to validate sources and provide authentic information to students about a culture, religion, song, story, or leader.

One such example is this quote, which I had wanted to use here to amplify my message. I found it online attributed simply as a “Chinese proverb”:

If your vision is for a year, plant wheat.

If your vision is for ten years, plant trees.

If your vision is for a lifetime, plant people.

Upon further research, I discovered that other nuanced versions of this sentiment exist; the following is attributed to the ever-popular Confucius, who most people presume to be China’s most famous philosopher:

If your plan is for one year, plant rice.

If your plan is for ten years, plant trees.

If your plan is for one hundred years, educate children.

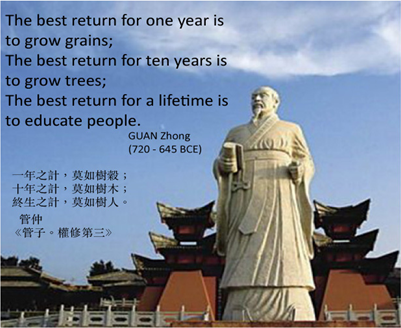

There is little difference between those quotes, but fortunately, I happened upon a blog post (Hung 2017) that provided the clarity I was seeking. The real author of the original quote, Chinese philosopher and politician Guan Zhong, predated Confucius by over 100 years. His statement was slightly different, as shown here, illustrated with a statue of the speaker:

Image used with permission from Billy Hung

Image used with permission from Billy HungAlthough the difference is nuanced, the meaning is less about the rate of growth than on the “return on investment.” This seems an even better metaphor for the work we do in anti-bias, culturally responsive teaching (CRT) through music. Had I used the first quote I found, I would have misrepresented and misattributed it. Where is the authenticity or cultural value in that? Again, it’s a matter of intent versus impact.

Peace Train

Many general education classroom and music teachers respond to the challenges of eliminating bias by simply focusing on general themes of kindness, the Golden Rule, friendship, getting along, fairness, and “multicultural” activities and music (making sure some songs are sung in languages other than English). Those themes are positive and socially appropriate for all ages. But in this period of easy access, swift change, cultural enlightenment, more diverse communities, heightened racial and historical awareness, and identity struggles, it is truly not enough.

Those who work with children have the unique opportunity—and, I suggest, the obligation—to take our students further in a direction that will serve them well for their lifetime. We need to transform our good intentions into actionable practice. Geneva Gay describes CRT as “using the cultural knowledge, frames of reference, and performance styles of ethnically diverse students to make learning encounters more relevant and effective for them. It teaches to and through the strengths of these students” (2010).

True music must repeat the thought and inspirations of the people and the time.

—George Gershwin

As educators, we are constantly planting seeds for a distant harvest, so we need to be vigilant that the seeds we sow are going help children become confident, resilient, critical thinkers who are connected to their identity and can handle all the social, emotional, political, economic, and educational challenges that lie ahead. We need to build on individual and cultural experiences to reflect the social context in which we are working. Culturally responsive teaching amounts to more than applying strategies; it is a mindset that positively impacts all students. “When done the right way,” says Cherese Childers-McKee from Northeastern University’s College of Professional Studies, “it can be transformative” for all students (Burnham, 2020).

A Change Is Gonna Come

How might a culturally responsive music class look, feel, and sound?

If you are already using multicultural music, teaching songs about social justice and anti-bias, and tuning in to what your students know and need, terrific! Perhaps you even have posters that illustrate people in non-Western countries playing traditional instruments. If so, you are already on the path to greater culturally responsive teaching!

But I am pressing myself to dig deeper, think harder, and be more thoughtful and proactive in my work in anti-bias, culturally responsive curriculum. While there is nothing wrong with what I am already doing, I know the more I read, collaborate, and communicate (particularly with people from different races and cultures and marginalized groups), the more I realize that I can—and should—be doing so much more. I challenge other white educators to adopt an even broader frame of reference for developing this kind of responsive learning environment.

Here are some of the features of creating an anti-bias, culturally responsive framework for teaching:

- You actively set your intentions to include music that reflects your teaching population and the students within. This will likely mean that you will need to ask a lot of questions of people who can assist you and compensate them in some way for their time and expertise, read widely on topics, and expand your professional development to include anti-bias; CRT; and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

- You continually reflect on teaching approaches you use, decisions you make, your expectations, and your engagements with diverse families. Consider how your teaching may be aligned with dominant cultural practices. Try to uncover any hidden biases or values you may hold that prevent you from fully engaging with all people or creating culturally responsive opportunities for learning.

- Relationship building is at the core of all you do! Developing respect and trust, maintaining honesty, and finding each child’s unique contribution go a long way toward building a positive class community in which all may thrive.

- You begin your work with students by gathering as much personal information beyond the school record as possible. Much of this comes from interacting with the students and parents/guardians, but you may also glean some of this information by sending home a questionnaire (in their native language) to foster the home-school connection. The answers to these types of questions should inform planning, curriculum development, and experiences. Here are two template forms: one a music class cultural questionnaire, the other a general education classes cultural questionnaire. (For translation, Google Translate and DeepL both work fairly well.)

- You take every opportunity to explore and engage in different cultural experiences yourself. Read books; attend fairs, events, or concerts; etc.

- You display through words, actions, and environment that your classroom is student centered. Students are involved in developing curriculum, activities, and assessment processes, and the room reflects their presence and their work.

- Your teaching is student strength- or asset-based. You identify and appreciate the unique identities, talents, experiences, skills, and knowledge of each student, staff member, parent, or other outside collaborator.

- You recognize that every person belongs to one or more cultures or groups (e.g., religious, family, ethnicity, race, community). Culturally responsive teaching is for all students. Even if you teach in an all-white environment, the lessons students learn through your responsive climate help them be better allies to folks outside of their classroom and school.

- You engage the students in curriculum development, having them design materials and activities to best reflect their culture and to strengthen their individual sense of cultural and racial identity.

- You actively promote equity and inclusion of all students by listening to, considering, and incorporating their perspectives in your work. This includes students of every socio-economic level, ethnicity, religion, immigration status, ability level, national origin, language, gender, sexual identity, and culture.

- Critical thinking is supported and expected of your students and yourself. Modeling is key!

- Students’ prior knowledge, and all their diverse experiences, are used as the foundation on which new learning is anchored.

- You provide context for all learning, clearly connecting students’ learning to social communities and to their life experiences. You find ways to help students create parallels and see the relevance of the material you are presenting. For example:

- If you are presenting a motivational or inspirational song, you choose one from your regular repertoire and one from a less familiar genre (e.g., folk and hip-hop), encouraging students to compare and contrast the styles, lyrics, and meanings of each song.

- You create interdisciplinary activities, like a lesson on figure of speech paired with a popular song that uses that feature.

- You bank on students’ “social capital,” cultural or otherwise. You find ways to give those students who typically have no voice (i.e., students who are still learning English, immigrants, children with special needs) a chance to be the experts by building on the strengths, experiences, and skills they do have (always checking with the student prior to doing so, however, so they do not feel singled out, tokenized, or uncomfortable).

- You provide an environment that reflects the children and community of your class/school through music, books, posters, and materials available or on display. You consider your LGBTQIA+, migrant, homeless, urban, and suburban students as well as those with differing abilities, recognizing that when multiple identities converge, they create unique experiences of oppression (e.g., a black woman; a lesbian who is Catholic).

- You invite student collaboration by arranging furniture to encourage discussion and participation, and by making relevant materials, books, and resources available.

- You communicate clear, high expectations for all students, regardless of race, language, or ability.

- You permit and respect all native languages and literacies.

- Translations and resources are available for students needing language support.

- You can speak a few basic words in each native language.

- You pronounce each child’s name accurately.

- You treat families as assets. Make frequent, positive family connections. Involve them in your planning as often as possible, making sure to provide communication in their native language.

- You reconsider and challenge your Western European–based curriculum and the “tourist” approach to multicultural music and education. The tourist approach relegates diverse cultures to singular holidays and sets them apart as “other”—marginalized from the norm. This approach (also called tokenism) offers only a brief glimpse into a holiday or traditions of a culture for a limited period of time (e.g., discussing diversity during the week of Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday, or honoring Hispanic heritage only during one month). This includes presenting music that does not reflect the diversity of your own classroom. To avoid the Tourist Curriculum:

- Begin by honoring the holidays and traditions of the cultures in your classroom before introducing other holidays or traditions.

- Reinforce acceptance and respect for the cultures in your classroom multiple times throughout the year through music, food, stories, dances, crafts, activities, visiting speakers, etc. Keep in mind that foods can represent a culture, but avoid stereotyping or associating only specific foods with a culture (e.g., tacos and Mexico).

- Invite members of a relevant culture/religion to share a holiday or custom with your class. This could include students’ parents, relatives, or friends; neighborhood business or restaurant owners; staff members; or members of local religious or cultural groups. Work to maintain these collaborations. Invite them to share what is relevant to them; don’t limit their contributions to a specific agenda or topic.

- Compare and contrast various customs and holidays. Be open to the students’ questions. Don’t worry about knowing all the answers yourself; but be sure to assist them in finding answers through authentic sources.

- Pair appropriate books, videos, instruments with songs from a particular culture. To avoid tokenism, provide multiple books and resources on a topic or culture.

- You appreciate that there are many different views on child development, learning, and behavior that are valued by people of different cultures. While you do not have to forfeit your own values, you can work to understand parents’ perspectives while positively educating them about the informed decisions you make for your students.

- You acknowledge that discussions about race and cultural diversity can be uncomfortable, but they are not inherently negative. It is vital to the future of music education and our students’ well-being to challenge the status quo if we want them to be meaningful participants in a global community. Invite constructive conversation and feedback from students, families, colleagues.

- You understand that your positive attitude toward diversity—your flexibility, support, empathy, humility, and appreciation for differences—matters more than whether you are an expert in multiple cultural practices and beliefs. Commitment to CRT and social justice, combined with a genuine interest, sensitivity, and curiosity to learn about your students’ cultures and lifestyles, are enough to provide the needed conversations and discoveries. That said, it is not enough to simply have a positive attitude without action.

- You challenge yourself not to simply include one song from an artist or composer of color, but to increase the number of music selections in your repertoire from such artists or composers by a minimum of one song per unit, theme, or semester.

- You explicitly challenge incidences of racism, stereotyping, or devaluing in class. Engage students in equitable discussion and problem solving.

I Can See Clearly Now

You may still be saying to yourself, “How is that different from what I already do?” I hope that everyone is able to teach in such a culturally responsive way! But in my experience, most educators are so driven by the existing curriculum, traditional teaching methods, habits, and—particularly for white educators—a level of discomfort discussing race and culture in such direct ways that this is not the standard in most schools—yet! While it is not always possible to abandon required curriculum, it is always possible to shift what you do, or how you do it, to be more culturally relevant to the students in front of you.

Photo credit: FFCU Sonamabcd

Photo credit: FFCU SonamabcdYou probably have many more questions, and that is a good thing! Some additional frequently asked questions about responsive teaching in the classroom are addressed here as well. And if your current curriculum does not reflect the practices of CRT, create your own or push for one that does. Our students depend on us to use best practices, even if it means that we do the pushing from our side rather than waiting for those at the top to deliver. Whatever you choose to do, be knowledgeable and prepared to explain your decisions. Listen to those who inquire, acknowledge the experts, and adjust accordingly when new information emerges.

In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.

—Martin Luther King Jr.

When we take the extra time to know the cultural and social capital of our students, we are better able to meet their needs, foster their sense of identity within and outside the classroom, and empower them to become critical citizens and learners. In these ways we can begin to make friends, not only with the children in our charge, but with that awkward, ginormous elephant in the classroom who has been preventing us from asking ourselves hard questions and having more challenging discussions about race and anti-bias work. Word has it that the elephant in our classroom is a lot more like us than we realize . . . and they are ready to make a new friend!

References

Alexander, Kevin. “All the Nursery Rhymes You Sang as a Child Are Creepy as Hell.” Thrillist.com. 12/28/2016.

Armstrong, Jocelyn. Personal correspondence. 11/3/2020.

Asante, Molefi Kete. “An African Origin of Philosophy: Myth or Reality?” 7/1/2004.

Attalla, Sue. “The War on the Hyphen: A Story Behind a WWI Song.” Blog. The Life and Times of Christopher O’Hare. 6/29/2017.

Boston Children’s Chorus (BCC). “Isn’t That Just Good Teaching? An Introduction to Culturally Relevant Chorus.” 4/2/2018. Checklist for thoughtful selection

Bradley, Deborah. “The Sounds of Silence: Talking Race in Music Education.” 2007. http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Bradley6_4.pdf

Burnham, Kristin. “Five Culturally Responsive Teaching Strategies.” Northeastern University Graduate Program. 5/31/2020.

Burton, J. et al. “A Brief History of Japanese-American Relocation During World War II.” NationalParkService.gov

Caldwell, Elizabeth. “Organized Chaos.” Blog. 6/2020. Anti-racism in Music Education

Derman-Sparks, Louise. “Selecting Antibias Books.” Teaching for Change. Updated 2013.

Derman-Sparks, Louise, and Merrie Najimy. “Children, Arab Heritage, and Anti-bias Education.” Social Justice Books.

Gay, Geneva. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. Teacher’s College Press, 2010. p. 31.

Gebreyes, Rahel. “Study Shows Most White Americans Don't Have Close Black Friends.” Huffington Post. 9/24/2014.

Gonzalez, Valentina. Culturally Responsive Teaching in Today’s Classrooms. National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE). 1/8/2018.

Hargraves, Vicki. “Principles for Culturally Responsive Teaching in Early Childhood.”

Holder, Nate. “Why Do You Sing Kye Kye Kule?”

Holder, Nate. “If I Were a Racist.” (lyrics) Blog. Used with permission from the author. 7/8/2020. Accessed 10/15/2020. NateHolderMusic.com

Hodson, Gordon. “Being Anti-Racist, Not Non-Racist.” Psychology Today. 1/20/2016.

Hung, Billy. “False Confucius quotes” from the blog While On Board, 4/3/2017.

Johnson, Theodore R. III. “Talking About Race and Ice Cream Leaves a Sour Taste for Some.” Code Switch. NPR. 5/21/2014.

Kanter, Jonathan and Daniel Rosen. “What Well-Intentioned White People Can Do About Racism.” Psychology Today. 8/10/2016.

Kelly-McHale, Jacqueline. “Why Music Education Needs to Incorporate More Diversity.” National Association for Music Educators (NAfME). 4/25/2016.

Kendi, Ibram X. How to Be an Antiracist. One World, 2019.

Kuehne, Jane M. “The Elephant in the Room: Race Conversations in Our Classrooms.” National Association for Music Education (NAfME). 6/30/2017.

McEvoy, Mike. “Reasons Google Search Results Vary Dramatically (Updated and Expanded).” 6/29/2020. WebPresenceSolutions.net

McWhorter, John. “Racist Is a Tough Little Word.” The Atlantic. 7/24/2019.

Merit School of Music. “Building an Anti-Racist Music School.”

Oare, Steve. “Embracing Unfamiliar Cultures in the Music Classroom.” Kansas Music Review. 10/10/2016.

Richardson, Ian. “ ‘Pick a Bale of Cotton’ dropped from Iowa school concert after criticism.” Des Moines Register. 4/16/2019.

Sarrazin, Natalie. “Chapter 13: Musical Multiculturalism and Diversity.” Music and the Child (free e-book).

Urbach, Martin. “You Might Be Left With Silence When You’re Done: The White Fear of Taking Racist Songs Out of Music Education.” National Association for Music Education (NAfME). 9/12/2019.

Utt, Jamie. “Intent vs Impact: Why Your Intentions Really Don’t Matter.” 7/30/2013. EverydayFeminism.com

Vozick-Levinson, Simon. “Can ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’ be redeemed?” Rolling Stone. 8/6/2020.

Waller-Pace, Brandi. “Ep. 8. Decolonizing the Music Room.” Podcast. MusicPeaceBuilding.com

Wyatt-Ross, Janice. “A Classroom Where Everyone Feels Welcome.” Edutopia. 6/28/2018.

Wood, Jennifer. “The Dark Origins of 11 Classic Nursery Rhymes.” Mental Floss. 10/28/2015.

For additional resources, music sources, blogs, articles, etc., click here.

I would like to acknowledge the insight and expertise shared with me by the people who took considerable time to review this article for content as well as form: Jocelyn Armstrong, Dorothy Cresswell, Ginger Lazarus, Lynne Lyon, Kaitlyn McGaw, Sarah Narayana, Susan Salidor, Devin Walker, Lolita Walker, Ashley Wise, Ceylon Wise.