A Few of My Favorite Things

I remember the day my graduate school professor, a woman I considered a mentor, casually mentioned in class that “Five Little Monkeys” and “Miss Mary Mack” (both also available as song picture books) were among many children’s songs and rhymes with a racist background. At first, I thought I had misheard her. “The words to ‘Eeny, Meeny, Minie, Moe’ originally included the n-word,” she continued. (How could that be? I’d known that rhyme my whole life and it only referred to a tiger!). She concluded, rather abruptly, with, “So you really should be aware that some of the songs and rhymes you may be tempted to use in your classroom may not be appropriate.”

My professor had, in one brief comment, completely upended everything I thought I knew about songs, rhymes, and folk songs for children. It has taken me nearly twenty years to reckon with this notion. Over the years, I have continued to seek more information, discussed the topic of “racist music” with colleagues, friends, and mentors, and spent a great deal of time trying to understand my role in ending—or perpetuating—music with such a negative history.

To be clear, racism is not the only bugaboo related to songs we find in homes and classrooms across the nation. A growing list of other familiar songs and rhymes rooted in racism, slavery, minstrelsy and other forms of discrimination whose original lyrics (or the knowledge thereof) continue to promote stereotypes may be found here: Discriminatory Children’s Traditional/Folk Songs.

If I were a racist,

I’d teach reggae music and Bob Marley,

‘Stir It Up,’ but never ‘War.’

I might even mention marijuana . . .

. . . If I were a racist,

I’d know that,

Even though the notes may be black,

The spaces would remain white.

—from “If I Were a Racist” by Nate Holder

Across many conversations and emails with peers, mentors, and fellow parents, I have heard numerous responses to this uncomfortable issue (I’ll stick with racism as the example, though you could replace racism with other -isms, i.e., forms of oppression, discrimination, and disenfranchisement), among which include:

I changed the lyrics so it doesn’t sound racist anymore.

If no one knows the original meaning, how can it harm them?

It’s such a great song/rhyme! I use it all the time, and no one’s complained. The kids love it! Why should I give it up?

It’s an important historical lesson best taught through song.

I don’t believe in banning or censorship (more currently referred to as a “cancel culture,” whereby anything seen as racist must be banned, stricken, removed, or publicly denounced). If we ban songs like this, the next generation is destined to repeat our racist actions because they won’t have learned the important lessons from the past.

You’re overthinking this! Why does everything have to be about race?

All these responses reflect the thinking of many white people—even some people of color—in the United States who grew up with these songs and never realized (or took seriously) the songs’ racist origins. To suggest that a teacher, parent, or artist stop using these songs is often taken as an affront to their self-identity (I’m not racist, so it doesn’t apply to me) and sense of musical integrity (These songs represent our cultural heritage and belong in our national repertoire. Otherwise, it’s censorship).

People Get Ready . . .

For those of us who use music to teach children, it is impossible to consider the potentially racist impact of music without considering the impact of what’s going on in our country (and world) right now regarding racism and other forms of discrimination that are so prevalent. While the deaths of black people at the hands of white police officers has created an exponential sense of urgency in regards to understanding racism, implicit bias, and white fragility (the defensiveness of white people when confronted with the role of whites in racial injustice or inequality), we must also acknowledge that our country has had white supremacy and systemic racism in varying degrees since it began, beyond the Civil War, and racial tensions beyond the Civil Rights movement, including these examples:

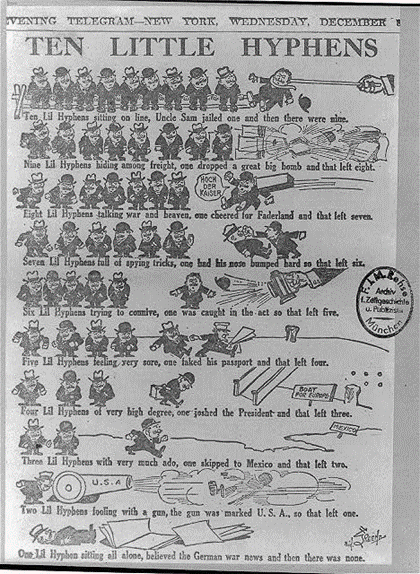

Sydney J. Greene, Dec. 1915. Retrieved from the Library of Congress

Sydney J. Greene, Dec. 1915. Retrieved from the Library of Congress

- indigenous people slaughtered for their land by whites/colonists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries;

- the Chinese Massacre following the Gold Rush of 1871, in which a mob of 500 whites and Mexicans robbed and killed residents of LA’s Chinatown;

- anti-immigrant laws and riots between various immigrant groups (e.g., Italians, Irish, Puerto Ricans, through much of the twentieth century);

- anti-German propaganda during World Wars I and II, such that there became a “war on hyphens”—the hyphen (e.g., German-American) indicating a sense of duplicity, or worse, a lack of loyalty to, or betrayal of, the United States;

- Japanese-American and German-American Internment camps during WWII;

- most recently, the nationwide protests by the Black Lives Matter supporters of all races that inspired similar protests worldwide.

To suggest the recent social upheavals are somehow new, prompted by a particularly contentious time in politics, a psychological response to long-term quarantine, or that something has “changed” to suddenly make people of color so upset, belies the awful truth: We’ve been in this spot for a long time, and we are all in this together, for as long as it takes—and that does not refer to the virus that has accosted our world.

While the complexities of systemic racism are difficult to address fully in one article, what we can do is focus on ways to move toward a goal to help build up one another as professionals while building up our students through the work we do with children and music based on a few vital assumptions:

1) Racism exists in our everyday lives.

Regardless of whether you view the cause as systemic, classist, power centrist, media influenced, social, economic, or simply how people were raised, racist acts occur every day, and are perpetuated by many people of all races (though primarily by whites, as the largest group of oppressors) both knowingly and unknowingly. Here are just a few examples:

- In switching to online teaching during the COVID-19 outbreak, we immediately realized that our educational system does not accommodate students without access to digital devices and consistent Wi-Fi as learning tools. At the very root of that disparity is racism, which is now impacting yet another generation of children’s education in a powerfully negative way. The potential is great for perpetuating this educational divide into future generations as the educational system is reevaluated.

- You may have heard, overheard, laughed at, or even participated in the telling of jokes that put a particular ethnic group, religion, race, or culture as the brunt of the joke. Perhaps you felt the brunt of the joke, or perhaps the joke referenced someone else’s culture or community. The playground is where many of us learned racial and ethnic slurs and stereotypes. As children, we absorbed all that damaging (and inaccurate) information. It is only through broader life experience and a willingness to challenge our own expectations that we learn to recognize those seemingly harmless jokes as cruel aspersions. But simply not repeating racist jokes is not enough; we must shift our intent (to do no harm) into impact by speaking out against perpetuating such slurs. The ghosts of the playground become the specters of complicit adults when not called out for what they are.

- Where I live, a new kind of aspersion is cast on what locals refer to as Apartment Kids—children residing in controlled rent (aka Section 8) housing in our upper middle-class school district. Despite the fact that the majority of parents there are working, participate eagerly in school functions, and are as supportive of their school-age children as parents in the surrounding neighborhoods, many white people deride these families for “bringing down property values,” “leaving their kids to run wild,” and “not caring.” It’s inaccurate, racist, classist; and children are watching and listening to the adults who purport all that, just as we had when we were kids.

- “I don’t see color” and “We are all part of the human race.” These are, at their root, statements that ignore one’s implicit bias by suggesting that the color of someone’s skin makes no difference at all. It actually goes further, by implying that one’s race or ethnic experience is not valuable, not worthy of being celebrated or respected as unique. But even those with less pigment want to acknowledge—and be acknowledged for—the special qualities that help make them who they are. We all know that race is not invisible, so it is only logical to acknowledge all our unique stories.

2) We all have biases.

This is true for black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) as well as non-BIPOC. Implicit, explicit, ingrained, situational, or lifelong, we all have them, despite our best intentions or wishes. Pretending otherwise slows down the process of getting to our better selves.

3) No single group/organization of people is monolithic.

As a parent of a child on the autism spectrum, there is a common saying used to describe the similar and yet very unique characteristics of such children: “If you’ve met one child with autism, you’ve met one child with autism.” And so it is with groups of people, whether associated by race, ethnicity, religion, sexual identity, class, etc.—no group speaks for or represents all people within that same group. Hence the challenge of understanding the dos and don’ts of these conversations! It is these discomforting sticking points that keep that elephant in our classrooms.

4) If you are reading this and you are white, you are probably

non-racist . . .

. . . even if your family once owned slaves, or you have cousins who still say “colored people.” Some scholars believe that the “opposite of ‘racist’ isn’t ‘not racist.’ It is ‘anti-racist.’” (Kendi 2019). Non-racist refers to the passive rejection of racist ideology (Hodson 2016). Furthermore, no one is saying “all whites are bad.” White people tend to feel defensive when the barrage of talk is about all the negative impact whites have had on people of color in our country, but that is just part of learning to “lean in” to the conversation and hear marginalized people. It is necessary to first put down defenses before one can really listen.

This is not about placing blame on whites or pushing whites’ guilt into action. The point is to acknowledge the myriad ways racism seeps into everyday life without white people recognizing it or calling it what it is, and the many ways they inadvertently perpetuate racism.

Although it is an incredibly bitter pill to swallow, after much soul-searching and learning, I can acknowledge that I am not racist, but I have benefitted from racism. While racism is an institution, not a person, that is not to say that no person is or can be racist (we know they can be, and are). It is the actions of racist individuals and groups—as well as the passive “non-racists”—who perpetuate the institution of racism, while preserving the benefits of racism for whites. This is not something I say, or feel, lightly. To be called racist is immediately horrifying to those of us with a conscience (I know this is you) and makes us feel defensive. The term racist bears vast semantic complexities, and, to make discussions more challenging, its social definition has morphed over the past years from being an overt action to being so ubiquitous as to not be recognizable (McWhorter 2019).

While the semantics may vary from person to person, group to group, I accept the notion that I am part of a racist infrastructure and society. For me, that means even though I grew up fairly poor in a single-parent family when divorce was taboo, I have experienced privileges, transgression oversight, friendlier public interactions, the benefit of the doubt, and the freedom to shop without being followed—actions usually not afforded people of color in the same situations. For example:

- I’ve been able to learn about the positive contributions of my race in school—specifically, in textbooks—while avoiding most mentions of any nefarious activities of my people. And there is no special month designated for this—it’s always White Month!

- The children’s books I grew up with always reflected kids who looked, thought, lived, and acted much like me.

- The media I follow positively reflects people of my race while frequently highlighting the travesties occurring in neighborhoods that are predominantly minority, or maligning people of color, before an investigation of a crime has even begun.

- If I search “beauty” in Google Images I’ll find the majority of images are of white women (no men), though in the last couple of years more women of color have been added to the results. That said, we now realize that Google and other online platforms tailor results to best fit the person using it. Perhaps what you see will be different? Try it and find out!

- Even the subtleties of language are used to disparage or defend, depending on bias (see image below). These are but a few of the “privileges” of being white in the United States and around the globe.

Used by permission from Mark Weinecke, Des Moines, IA via Twitter

Used by permission from Mark Weinecke, Des Moines, IA via Twitter

Because I am just beginning this journey to comprehend what racism means to me, to my community, and for our future, I also recognize that my ideas or actions may sometimes still reflect my experience within that racist system. I am trying to move from my passive non-racist thoughts and actions to those that will uplift and support people of color as well as other disenfranchised groups who've had little in the way of equity.

The term racist means one who is actively engaged in prejudice or antagonism—whether intentionally or passively—against people based on their race, color, or ethnicity. As you read and communicate more with other people, you may choose a different term, but based on my experience thus far (subject to further enlightenment), this is the term I have chosen to use and how I think it pertains to me and all who embark on this path.

I am not actively or knowingly engaged in prejudiced behaviors. At the most basic level—the very beginning of this journey toward reckoning—I am non-racist. I do not intentionally or actively believe in the inferiority of other people due to race (or anything else, for that matter). That said, it is important to note that even people who do not intentionally (explicit bias) behave in racist ways can still be racist without realizing or acknowledging it (implicit bias). Of course, I believe that being a non-racist is better than being an active racist—but it is still too passive a position to make any real difference; even tacit complicity perpetuates racist systems. I must accept the challenge to do more than be non-racist. Although there is a learning curve and I know I will continue to get some things wrong, in fact, I’m working very hard to identify, acknowledge, and eliminate those unconscious biases in my personal and professional life. My ultimate goal: Moving beyond non-racist toward anti-racist.

I am an individual woman; I am not all women.

I am responsible for my actions; not for those of previous or other racists.

I am an individual white, but I do not represent all whites.

I have been indoctrinated into a racist system of education, employment, economy, housing, representation, and social networks that most benefit whites; but I am not all racists.

I cannot make up for all the injustices of the past; I can act to prevent them from continuing.

5) Music has the capacity to touch, move, and impact people at their most emotional and vulnerable levels.

That’s why we’re all here.

Breaking Up Is Hard to Do

“First do no harm” is an ethical mandate usually attributed to the Hippocratic oath taken by doctors, and often cited as a directive for people in all types of helping professions, including education. The intent of an action (teaching a song, reading a book, sharing an artifact, etc.) must be to honor and respect the culture and people, though we know intent is not sufficient to pardon us from potential harm. Therefore, we must be confident that the possibility for good substantially outweighs the potential for causing damage. This is, I believe, a good way to consider our decisions about what songs to include or exclude in our repertoire, and how we will approach teaching about cultures outside our own.

While white people may be tempted to keep a song in their collection because it suits them for various reasons, white people must acknowledge that they are not at the center of the potential damage. Consider who actually hears the songs we teach to children: Classmates, parents, grandparents, other relatives, neighbors, teachers, students, concert-goers of all ages and backgrounds, administrators, friends . . . anyone with whom the children come into contact may well hear the songs we teach being sung either casually or formally.

While students may not actually know the sordid history of a song, it is likely that the adults around them do. Is the potential benefit of teaching kids to sing “Pick a Bale o’ Cotton” greater than the possible damage if children learn the racist origins from the other adults in their lives? If you’ve changed the lyrics of “Five Little Monkeys” to “Five Little Robots” but the tune or chant is the same, are you confident that no one outside of the classroom will recognize the tune and be hurt?

So much folk music relies not on the written score and lyrics, but on oral tradition. I think it is safe to assume that parents, grandparents, and older relatives (at least) will likely recognize the rhyme or tune even without monkeys in the lyric. In just one such instance from an Iowa school in 2019, a black parent’s complaint (based on her daughter’s concern) required a last-minute removal of “Pick a Bale o’ Cotton” from a spring choral concert that was “highlighting periods of American history” (Richardson 2019).

The diversity in the human family should be the cause of love and harmony as it is in Music where many different notes blend together in making the perfect chord.

—‘Abdu’l-Bahá

If we are not only to “do no harm” but also weigh the potential harm versus good, it seems easier to comprehend the depth of pain that the melody of a song can bring to someone who has experienced that song through a very different lens. Just as some songs provide joyous memories and feelings, particularly for those of us working with music and humans, songs with negative associations evoke pain that is impossible to ignore.

This is where understanding “intent” and “impact” is critical. Intent is self-centered (I) and explains what you planned to have happen that may (or may not) have worked out as expected. Impact has a broader view (we) and is the resulting change created by your intentions (Armstrong 2020). You may have intended to be ready to leave for work on time, but you are running late. The impact is that you’re late, your first session of the day had to be cancelled or postponed, you’ve inconvenienced the other people involved, and you’ve set a negative tone for the day not only for yourself, but for the others who were inconvenienced by your lateness.

There are so many possibilities and variables involved in determining what songs to include in your repertoire for work with children. Unfortunately, I don’t have the answers, either! But I can share Thinking Points (or Talking Points, if you can find someone to share them with) that may help you consider your choices, perhaps through a new and different lens. This is intended for anyone who works with children and music; I used “Music Educator” as the broadest role that might encompass us all. Click the title to view the checklist. And join me next time for Part II of this article, focusing on working toward culturally responsive teaching.

A Thinking Music Educator’s Checklist for Multicultural Unbiased Music

I would like to acknowledge the insight and expertise shared with me by the people who took considerable time to review this article for content as well as form: Jocelyn Armstrong, Dorothy Cresswell, Ginger Lazarus, Lynne Lyon, Kaitlin McGaw, Sarah Narayana, Susan Salidor, Devin Walker, Lolita Walker, Ashley Wise, Ceylon Wise.

References

Alexander, Kevin. “All the Nursery Rhymes You Sang as a Child Are Creepy as Hell.” Thrillist.com. 12/28/2016.

Armstrong, Jocelyn. Personal correspondence. 11/3/2020.

Asante, Molefi Kete. “An African Origin of Philosophy: Myth or Reality?” 7/1/2004.

Attalla, Sue. “The War on the Hyphen: A Story Behind a WWI Song.” Blog. The Life and Times of Christopher O’Hare. 6/29/2017.

Boston Children’s Chorus (BCC). “Isn’t That Just Good Teaching? An Introduction to Culturally Relevant Chorus.” 4/2/2018. Checklist for thoughtful selection.

Bradley, Deborah. “The Sounds of Silence: Talking Race in Music Education.” 2007. http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Bradley6_4.pdf

Burnham, Kristin. “Five Culturally Responsive Teaching Strategies.” Northeastern University Graduate Program. 5/31/2020.

Burton, J. et al. “A Brief History of Japanese-American Relocation During World War II.” NationalParkService.gov

Caldwell, Elizabeth. “Organized Chaos.” Blog. 6/2020. Anti-racism in Music Education.

Derman-Sparks, Louise. “Selecting Antibias Books.” Teaching for Change. Updated 2013.

Derman-Sparks, Louise, and Merrie Najimy. “Children, Arab Heritage, and Anti-bias Education.” Social Justice Books.

Gay, Geneva. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. Teacher’s College Press, 2010. p. 31.

Gonzalez, Valentina. Culturally Responsive Teaching in Today’s Classrooms. National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE). 1/8/2018.

Hargraves, Vicki. “Principles for Culturally Responsive Teaching in Early Childhood.”

Holder, Nate. “Why Do You Sing Kye Kye Kule?”

Holder, Nate. “If I Were a Racist.” (lyrics) Blog. Used with permission from the author. 7/8/2020. Accessed 10/15/2020. NateHolderMusic.com

Hodson, Gordon. “Being Anti-Racist, Not Non-Racist.” Psychology Today. 1/20/2016.

Johnson, Theodore R. III. “Talking About Race and Ice Cream Leaves a Sour Taste for Some.” Code Switch. NPR. 5/21/2014.

Kanter, Jonathan and Daniel Rosen. “What Well-Intentioned White People Can Do About Racism.” Psychology Today. 8/10/2016.

Kelly-McHale, Jacqueline. “Why Music Education Needs to Incorporate More Diversity.” National Association for Music Educators (NAfME). 4/25/2016.

Kendi, Ibram X. How to Be an Antiracist. One World, 2019.

Kuehne, Jane M. “The Elephant in the Room: Race Conversations in Our Classrooms.” National Association for Music Education (NAfME). 6/30/2017.

McEvoy, Mike. “Reasons Google Search Results Vary Dramatically (Updated and Expanded).” 6/29/2020. WebPresenceSolutions.net

McWhorter, John. “Racist Is a Tough Little Word.” The Atlantic. 7/24/2019.

Merit School of Music. “Building an Anti-Racist Music School.”

Oare, Steve. “Embracing Unfamiliar Cultures in the Music Classroom.” Kansas Music Review. 10/10/2016.

Richardson, Ian. “ ‘ Pick a Bale of Cotton’ dropped from Iowa school concert after criticism.” Des Moines Register. 4/16/2019.

Sarrazin, Natalie. “Chapter 13: Musical Multiculturalism and Diversity.” Music and the Child (free e-book).

Urbach, Martin. “You Might Be Left With Silence When You’re Done: The White Fear of Taking Racist Songs Out of Music Education.” National Association for Music Education (NAfME). 9/12/2019.

Utt, Jamie. “Intent vs Impact: Why Your Intentions Really Don’t Matter.” 7/30/2013. EverydayFeminism.com

Vozick-Levinson, Simon. “Can ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’ be redeemed?” Rolling Stone. 8/6/2020.

Waller-Pace, Brandi. “Ep. 8. Decolonizing the Music Room.” Podcast. MusicPeaceBuilding.com

Wyatt-Ross, Janice. “A Classroom Where Everyone Feels Welcome.” Edutopia. 6/28/2018.

Wood, Jennifer. “The Dark Origins of 11 Classic Nursery Rhymes.” Mental Floss. 10/28/2015.

Keep going for additional resources, music sources, blogs, articles, etc.