As educators and performers working with very young children, we know that music is a special activity that uniquely connects language, movement, physical senses, emotions, and memory. Each of these functions is centered in different areas of the brain. When we activate all these functions through music, we activate a network of connections that involves many different parts of the brain and many different structures. Through our work, we help to create and establish these networks of brain cells, or neural networks.

These neural networks develop at a rapid pace as babies learn and grow. Music is a rich activity that stimulates brain cells (neurons) to send electrical impulses that travel from cell to cell, and stimulates chemicals called neurotransmitters that help to carry these signals. We experience these complicated patterns of connections as thoughts, feelings, and memories.

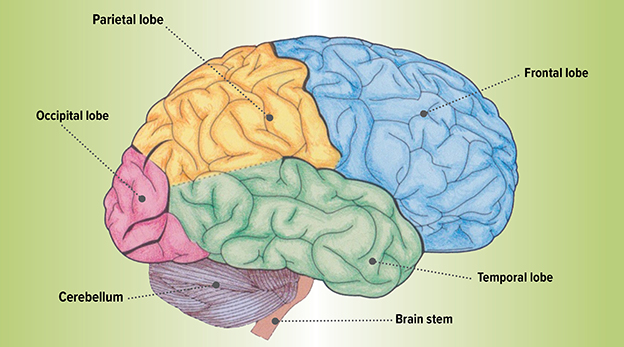

When people first started studying the human brain, they were eager to create maps that showed which parts of the brain controlled which function. They studied the many folds (gyri) and valleys (sulci) of the outer layer of the cerebral cortex, our grey cells. From that work, we learned certain critical information, such as the location of the sensorimotor strip that goes all the way across the mid portion of the brain along the border of the frontal and parietal lobes.

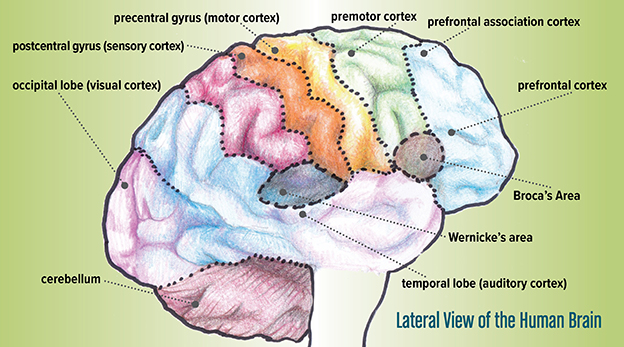

Groups of cells along the strip of motor cortex (the pre-central gyrus) control movements of each body part, while the cells on the side of the sensory cortex (the post-central gyrus) receive sensations. We learned that the amount of cortical surface area is proportional to the sensitivity of that area; for example, a larger amount of brain real estate is connected to the face and hands.

While there was great value in creating those maps and understanding how location and function are tied together, it didn’t accurately capture much of the complexity that exists in the brain. It also gave rise to misleading conclusions, such as the idea that we only use 20 percent of our brains, which is completely false. The reality is that we are still figuring out much of the puzzle that is the human brain.

Given that, it’s natural to wonder if there may be some hidden center that is the key to music processing. However, while it is fascinating to think that there might be a music center that we can point to, focus on, and easily identify, it’s a somewhat outdated way of thinking about the brain and doesn’t accurately encompass the beautiful and magical complexity of its relationship to music.

At an immediate level, our auditory receptors pick up the sound waves and translate that information into pitches and percussive elements. This first level of processing takes place in the auditory cortex in the temporal lobe. If lyrics are attached to that sound, we involve the language processing areas of the brain.

We’ve identified language areas from those original brain maps as well as from studying patients, such as stroke patients, who had very specific damage to certain areas of the brain. We can see the areas dedicated to language are concentrated at the borders of the parietal and temporal lobes. We know our brains process the words to songs in Wernicke’s area, responsible for language comprehension and speech cognition, which just happens to be adjacent to the primary auditory cortex. When we sing along, we’re involving Broca’s area, which is responsible for language production and speech formation. The fact that these areas are near one another isn’t a coincidence or happy accident; it’s a reflection of the growth that comes with learning.

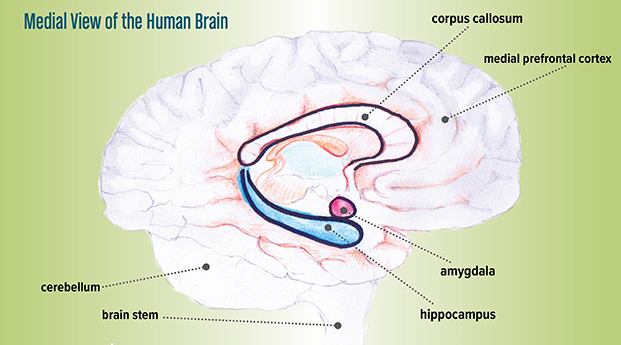

Meanwhile, directly under these areas are the deeper structures of the brain that process memories and emotion. The amygdala processes emotional memories, while the hippocampus is critical for long-term memories and processing experiences and context. The close proximity of these areas to both language and auditory areas may partially explain why musical memories are both emotional and powerful long-term memories for most people.

Going back to our example of the brain picking up a sound that activates a neural network, let’s imagine the sound comes from a hand clap: we see the action, hear the sound, and make the connection between the two. Now we’re activating the visual cortex in the occipital lobe, which is not far from the auditory cortex in the temporal lobe, just on the other side of the language areas we mentioned earlier. Between the primary auditory and visual cortex are areas responsible for processing all this information.

Adding another layer is our sense of proprioception or kinesthetic awareness (controlled by the cerebellum), which is the perception or awareness of the position and movement of the body. As we move, dance, tap our foot or lap to the beat, clap our hands, or sing along to these sounds, we now have a physical connection between the movement we’re producing and the auditory information. Our awareness of how far to move our limb while shaking a shaker, hitting a drum, or clapping our hands; how we balance our bodies as we dance; and the way we plan, control, and coordinate that movement are all part of this network. We’re quickly involving larger swaths of the brain in our music perception and music-making activities.

Counting and number sense also enter the picture as we count along to the beat. Recently, scientists have been able to measure and quantify the link between beat making and neural encoding of speech, connecting that, in our brains, rhythms of speech are tied to how we keep a beat when making music.

Other research has shown the connection between bigger movements that incorporate larger portions of that sensorimotor strip and a burst of language development in young children. The physical closeness of these brain regions (areas involved in movement production being adjacent to Broca’s area, controlling speech production) have a functional connection. All of this shows how complex and interconnected all these regions are, and how they all relate to music.

In addition, these areas border on other areas with functions that are necessary for music making and dancing. For example, the pre-motor cortex is involved in the planning of movement and trajectories. That area is right in front of the motor cortex, and it only makes sense that these two areas would interact: the part of the brain dealing with direction and distance of movement must be connected to the neurons that move that part of the body. Meanwhile, in front of that, the prefrontal association cortex is involved in planning, decision making, and personality traits. It’s also logical that the area that plans and decides to make a movement is connected to the area that chooses direction and distance, and that that is connected to the area that moves that body part. All these areas work seamlessly together while we move along to the music or complete a sequence of dance moves while we’re listening to or singing a song.

Further forward and central in the frontal lobe, but adjacent to these pre-frontal association areas, is the medial prefrontal cortex. This area seems to link music, memories, and emotion, and has been found to be one of the last areas to deteriorate in Alzheimer’s disease. Because these are deep connections storing our unique memories for music, and because these pathways connect to other areas of the brain that process music, they can sometimes provide a path to communication even when the typical language production and processing areas are damaged.

Whether we’re honing our gross or fine motor skills as we sing, laying down memories and feeling emotions, or listening to the lyrics and singing along, we’re strengthening our vast neural pathways and integrating language areas and sensory processing

areas.

Whether we’re honing our gross or fine motor skills as we sing, laying down memories and feeling emotions, or listening to the lyrics and singing along, we’re strengthening our vast neural pathways and integrating language areas and sensory processing areas. Plus, whenever we do bilateral movements—on both the right and left side of the body—we’re sending signals across the large bundle of neurons that connects the two hemispheres of the brain, the corpus callosum. Communication between the left and right hemispheres takes place via the signals that travel across this huge bundle of nerves, with each hemisphere controlling the opposite side of the body. We can think of the body as having a vertical line from the ceiling to the floor called the midline. When our movements cross the midline, the signals we send across the corpus callosum facilitate coordination between the hemispheres.

Through our music work, we establish patterns and set up those neural networks and pathways that tie together many different parts of the brain. Music nurtures critical development of gross and fine motor skills, as well social and emotional development, and integrates sensory-motor experiences. This happens seamlessly and simultaneously, whether you’re aware of the process or not.

All of this is to say that music is everywhere in the brain. Reception of sensations, movement, proprioception, language, memory, and emotion are all part of this network. The effects of music are real and measurable. They are reflected in the structure of our brains, and they reiterate the common knowledge we instinctively and intuitively know as educators and performers. Music is a powerful learning tool and is critically important to human development.