SaulPaul in concert

SaulPaul in concert

Make a Rainbow

Musicians of Color Reflect on the World of Children’s Music

by Liz Buchanan

The world of children’s music can seem like a very white place. Only a few people of color attended CMN’s 2018 international conference, even though the CMN Board held a retreat focused on diversity, and the keynote and Magic Penny Award both featured African Americans.

I thought back to 2012, when I interviewed the popular family musician, Dan Zanes, for the CMN Blog, exploring Zanes’s passion to bring more people of color into children’s music. Zanes, who’s white, said children of all colors should have a chance to see and hear musicians who look like themselves.

At the Kindiefest event that year in Brooklyn, Zanes challenged the mostly white crowd of family-oriented musicians to populate their bands with people of color and invite local musicians of different cultures to share the stage with them at family concerts. A couple bands led by people of color played at the event, but the performers were largely white.

Seven years later, it feels like not much has changed. I set out to revisit the topic of diversity in the world of music for

children and families by checking in with some of my favorite performers:

Devin Walker (the Uncle Devin Show),

Ashli Cristobal (Jazzy Ash), Andrés Salguero and his wife and performing partner,

Christina Sanabria (123 Andrés), and my newest favorite,

SaulPaul.

I caught up with Devin as he began a new chapter in his professional life, finally working full-time in the field of children’s music. At the end of the summer of 2018, Devin left his job with the DC Metro system after twenty years as an Equal Opportunity Employment officer. While handling discrimination complaints for the Metro, he was taking his “drumcussion” show on the road, offering a hundred performances a year for schools and family audiences.

Uncle Devin (Devin Walker)

Uncle Devin (Devin Walker)

Recently Devin branched out into the world of radio, hoping to bring more age-appropriate music into the lives of African American

children and families. He’s got a new program on Radio One (Washington’s WOL-1450AM), as well as an internet show

called “I am W.E.E. Nation.” W.E.E. stands for “Watoto

Entertainment and Education,” watoto being the word for “children” in Swahili.

For both shows, Devin’s focus is on steering family audiences and educators toward African American musical styles and performers of color who offer music for kids. His web page touts his Radio One talk show “for parents, teachers and other caregivers of children of African descent and beyond.”

Devin says too many African American children regularly listen to inappropriate music and are exposed to other entertainment for mature audiences. He’s passionate about eliminating what he calls music “adultification,” especially among children of color. He wants families and educators to know there’s better music out there for their children.

Who’s making that music? The first person Devin mentions is SaulPaul. Based in Austin, Texas, SaulPaul is on the rise as a singer and community leader. He was named 2017 Austinite of the Year by the Austin Under 40 Awards and honored in December 2018 as a Rising Leader by the Texas Civil Rights Project. He’s given two TED talks and has been featured in the Austin City Limits and South by Southwest festivals.

SaulPaul’s “Rise”

SaulPaul’s musical career is epitomized by his song and video “Rise,” which he calls “acoustic hip-hop.” His newest project is All Star Anthems, described on his web page as “an inspiring dance album for grade school audiences that promotes social and emotional learning.” The album includes a collaboration with 123 Andrés on the song “Home,” featured in a lively dance video starring both performers.

I checked in with SaulPaul in his hometown of Austin, and he echoes Devin’s concern about the content of music, other entertainment, and literature consumed by African American children. He points out that not only are these children often offered inappropriate content, even child-oriented content usually doesn’t reflect the world of children of color.

SaulPaul and 123 Andrés in “Home”

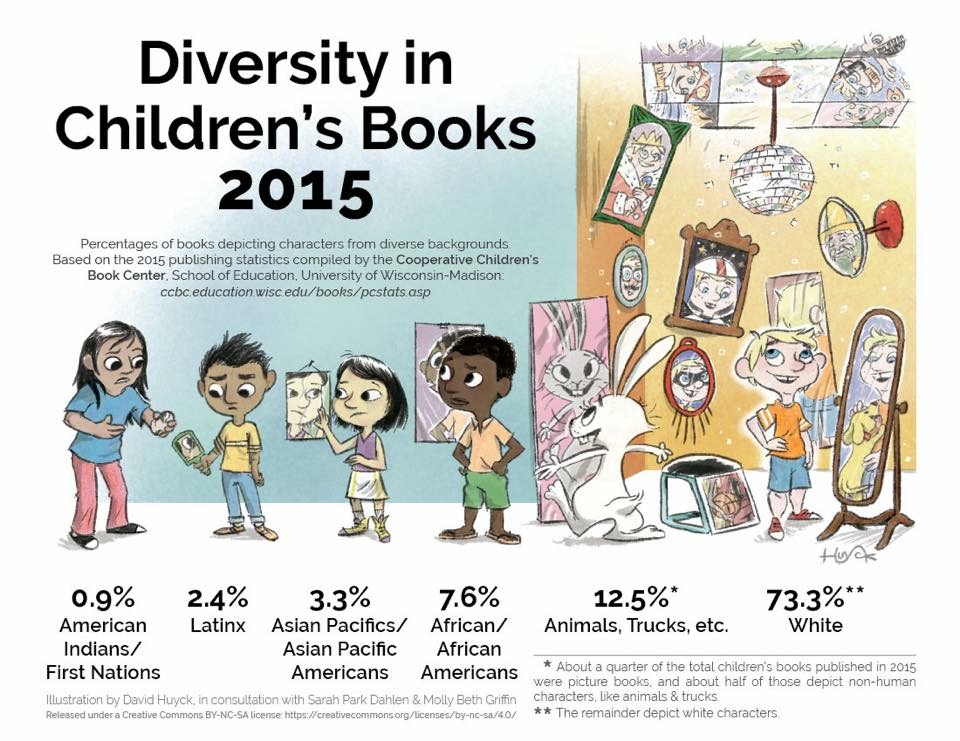

He sent me a telling graphic about children’s literature, compiled by the Children’s Book Center at University of Wisconsin-Madison,

based on publishing statistics in 2015. White characters are featured in 73.3% of books, followed at 12.5% by nonhuman characters such as

animals or trucks. Humans of all other ethnicities make up the remainder, with 7.6% African Americans, 3.3% Asian Pacifics/Asian Pacific

Americans, 2.4% Latinx, and 0.9% American Indians/First Nations.

Speaking about his music, SaulPaul says, “My goal is to make it appropriate for children, to be family-friendly, entertaining,

inspiring, and empowering.” He’s a role model for kids but also serves as an example for other musicians of color who might

follow the same path. “I did it, you can too; and here’s how you do it,” he says. There are lots of options, SaulPaul says,

for musicians who want to get into children’s music, such as playing at festivals, libraries, family shows, and schools.

Other performers of color on Uncle Devin’s playlist are New York’s Father Goose,

who released a new CD, King of the Dance Party, in 2018, and Jazzy Ash, based in Los Angeles. Her fourth album, Swing Set,

came out in July 2017, filled with classic children’s songs set to the sounds of New Orleans jazz and swing. Another DC-based black artist,

Jessica “Culture Queen” Hebron, is better known to CMN members, as she delivered the keynote at the 2014 conference and edited the CMN blog.

I asked Devin how to get more people of color interested in offering music for children.

“It’s hard,” he says. “The key is letting people know you can diversify.”

This could mean continuing to play for adults at night while developing shows for schools and family audiences. He points out that groups such as Wolf Trap and Young Audiences are always seeking new people of color to add to their rosters of performers and teaching artists.

“It’s important for children be able to see people [in entertainment, media] who look like them,” Devin says, echoing SaulPaul and many others.

I brought up this topic with Jazzy Ash, known in her nonperformance life as Ashli Cristobal. I first met Ashli (and Devin) at Kindiefest. She brings a bouncy New Orleans flourish to her performances; she also works in schools as a teaching artist and leads workshops on jazz and the classic children’s songs of black America.

Jazzy Ash (Ashli Cristobal)

Jazzy Ash (Ashli Cristobal)

Ashli says that, when she started touring, “I realized how few children of color see people who look like me.” She says families of color started travelling to see her just to expose their children to a performer who reflected their culture.

One possible barrier to more people of color getting into children’s music, Ashli points out, is that some cultural communities don’t recognize family and children’s music as a genre. “I don’t know if people realize this is a thing,” she says. “The idea of children’s content might not be a universal truth.”

Like Uncle Devin and SaulPaul, Jazzy Ash seems determined to change that reality. The album Swing Set offers fresh, jazzy

renditions of children’s songs with origins in the black community,

including “Hambone” and “She’ll Be Comin’ ’Round the Mountain.”

The video of “Hambone,” shot in the recording studio and featuring Uncle Devin, is not to be missed.

Jazzy Ash and Uncle Devin record “Hambone”

Ashli points out that too often, the black origins and original spirit of these songs—and those of many Negro spirituals—have

been lost as they have become assimilated into mainstream white culture. She supports efforts by groups like the

Carolina Chocolate Drops to showcase music “the way people did it originally.” Her workshops on children’s music have a similar goal, along with exposing children to jazz.

For another perspective on this topic, Ashli pointed me to a mutual friend and amazing musician from the Latinx community, Andrés

Salguero of 123 Andrés. Normally, Andrés lives in Virginia, but I caught up with him on Skype, along with his wife and

co-performer Christina Sanabria, between shows in Bogotá in his native Colombia.

123 Andrés has recorded three albums, the latest a collection of Spanish lullabies called Luna. The band’s 2016 release, Arriba Abajo, won the children’s music Latin Grammy as well as a Parents’ Choice Gold. Andrés says he and Christina are happy to add variety to the children’s music scene by offering Spanish/English children’s music with authentic sounds of South America and the U.S. Latinx community. Some of their biggest fans are Latinx families, but he says they also attract progressive families who are concerned about the current administration’s hostility toward people of Hispanic heritage. These families want to expose their children to a more positive image.

“We know the social and political context,” Andrés says. “We’re happy to do what we do.” He added that he’s very happy Christina has become his co-performer. “Girls need to see that!”

123 Andrés (Christina Sanabria and Andrés Salguero)

123 Andrés (Christina Sanabria and Andrés Salguero)

Andrés expresses concern about “whitewashing” in the entertainment industry. The mainstream culture often practices cultural appropriation, picking up on a theme in Black or Latinx culture and repackaging it for white audiences. An example would be an Asian or Latinx character played by a white actor, or a white singer imitating rap or hip-hop in a way that’s not authentic.

He adds that in children’s music, as in other genres, it’s easy for white musicians to get complacent, giving lip-service to diversity and progressive values, but not actively working to disrupt the cycle of discrimination.

For recording artists, he makes this suggestion: “If you do a song that’s not in your native language, find someone who speaks that language to sing it for you.” He notes that he’s worked to find new voices and musicians from all over Latin America to be part of his band’s performances and recordings. “If we all did some of that, it would help break that homogeneity,” he says.

Christina mentions that “often the gatekeepers are white,” including festival booking agents and radio hosts. These people are looking through the filter of their own taste and sometimes aren’t reliable judges of quality.

“We have to work twice as hard to prove ourselves,” she says.

I asked all these musicians how a mostly white organization such as CMN could become more diverse and better serve communities of color.

Devin, Andrés, and Christina have participated in CMN events, especially in the greater Washington metropolitan area, and are friends with many CMN members. They say time is a factor limiting their participation. Christina describes their schedule as “maxed out.”

Devin suggests that CMN might focus more on helping performers with the business side. All these performers seem to agree that making a living as a musician for children can present a major challenge for someone starting a career, especially for those who don’t come from affluent backgrounds. Devin points out that the folk-oriented style of many CMN members—as well as the generational divide—might also limit CMN’s appeal to a younger, more diverse population of potential children’s performers.

Meanwhile, he’s working on growing the field of African American musicians who sing for children. Especially with his new radio shows, he also wants to win over parents, creating a listening audience for this new subgenre of children’s music.

He points out that black musicians have had such a huge role in shaping American musical history, but right now they’ve got an undersized role in providing quality music for children.

“I’m trying to elevate this in the black community,” Devin says. “We need to win over the minds of people who have the vision to see what we can do.”

Thoughts? Ideas? Responses? Email Liz at antelopeliz@gmail.com to keep the conversation going.