The Gift of Your Honest Self

An Interview with Fred Rogers

by Phil Hoose

During the minute or so that I am on hold, waiting for Fred Rogers to pick up the phone, I grow increasingly tense. The next voice I hear will belong to a man whose sweater is in the Smithsonian, along with the Spirit of St. Louis and pterodactyl skeletons and Archie Bunker’s chair. He is one of the most identifiable figures in American life. When he finally does answer, how many other callers will be on hold as I scramble for whatever I can get of his time?

And then the voice arrives and instantly everything is all right. It is a slow voice, offered with modulation and care. There are spaces between words and bigger spaces between sentences. The words themselves are simple. Time slows by the syllable. Fred Rogers speaks to me as he has spoken to my daughters and as he speaks to millions of children in homes and day care centers each morning, and with the same effect. I am certain that there is no one on earth with whom he would rather be talking. I am special. I am good. I am a Neighbor.

The interview becomes a conversation. I ask him a question and sometimes there is no answer at all for a while.

After it comes, often he wants to know what I think. “Is that the way it is for you?” he asks. “Do you agree?” he wonders. Assistants may be slipping him notes from all directions, but I sense that he really wants to know. If I offer a thought or an insight, he takes time to consider what I’ve said and finds ways to affirm something about it. The same care and humanity, the same basic regard for a person’s worth, comes through the phone as comes through the screen. He is what he is. When one is with Fred Rogers in any medium, the message is clear: Together, as safely and calmly as possible, we’re all in the Neighborhood.

Fred McFeely Rogers was born in 1928 in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. His family was involved in banking and manufacturing. He has one adopted sister, eleven years younger than he. Fred went to high school in Latrobe, then majored in music composition at Rollins College in Florida. After graduation in 1951, he was hired by NBC in New York and became a part of some of the most important and exciting programs in the early history of television, including The Voice of Firestone, The Lucky Strike Hit Parade, The Kate Smith Hour, and The NBC Opera Theatre.

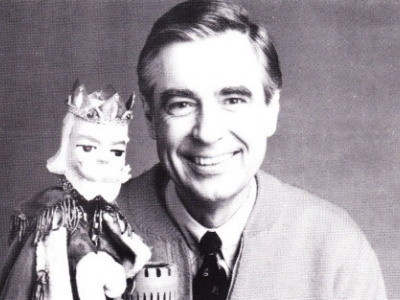

In November of 1953 Fred moved to Pittsburgh to develop program schedules for WQED, the nation’s first community-supported public television station. One of the programs he developed and produced was called The Children’s Corner. It was a live, hour-long visit with Fred’s puppets and host Josie Carey. Several later-to-be Neighborhood regulars were born on that show, including puppets Daniel Striped Tiger and King Friday XIII. During the seven years of The Children’s Corner Fred began to study childhood development and also to attend the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. He was ordained as a Presbyterian minister in 1962.

In 1963, Fred created a series called Mister Rogers for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. For the first time, he appeared on camera as the series host, and it was the precursor to the format he developed for Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, first distributed through PBS in 1968. Today, the program reaches more than seven million families each week and there are more than 600 episodes in the series. Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood is the longest-running children’s program on public television. Fred Rogers has won nearly every children’s television programming award available, including Emmys as a performer and as a writer.

According to Neighborhood’s press kit, the most important goal of the series is to “Encourage children to feel good about themselves.” Often, he tells his young viewers that “You are the only person like you in the whole world,” and “people can like you just because you’re you.” During an episode viewers visit both the “television house,” in which Mr. Rogers talks with young viewers, shows them things of interest, and escorts them to places where everyday things are made or done; and the “Neighborhood of Make Believe,” a mostly puppet kingdom in which Mr. Rogers never appears. It is a deliberate separation, intended to help children realize the difference between reality and fantasy.

It has always been a musical neighborhood. Fred Rogers has written over 200 songs for children as well as thirteen musical stories. Often, segments are accompanied by the elegant piano of Johnny Costa, a nationally known jazz pianist.

This interview took place by phone from Fred Rogers’ office in Pittsburgh. Fred discusses the challenge of maintaining an island of calm in a rapidly accelerating and often violent television environment. He talks about the role of music in his work and about his early life with music.

Fred lives with his wife in the Pittsburgh area. They are the parents of two married sons and are the grandparents of boys who were born in 1988 and 1993.

Phil Hoose: What are your early memories of music?

Fred Rogers: One of the first is of my grandfather McFeely. We named Mr. McFeely, the speedy delivery person, after him. He loved to play the fiddle. I’ll never forget the time I was able to accompany him on piano. His favorite song was “Play, Gypsy, Dance Gypsy, Play While You May” (sings it). I played the piano at his house and he played the fiddle. And to think that I am a grandfather now, and I have two grandchildren, six years old and two years old. The other night the two-year-old patted the piano bench, which meant that he wanted me to sit there and play. And when I play, I wish you could see him dance! He takes one foot and puts it down and sways and puts the other one down and sways back and forth. He’s very musical, I think.

Did your parents sing to you when you were little?

I have a feeling that they did. They always told me stories about my listening to the radio and then I would either hum what I heard, or, after my grandmother McFeely bought me a piano, I would go to the piano and pick out the tunes that I had heard. So radio and books meant a lot to me too. There wasn’t such a thing as television then. They remember taking me to movies when I was five or six. Then I would come home and play the songs from the movie. I always played by ear. I wanted to learn to play the organ, so my grandmother got me a Hammond organ. Evidently, when I was about ten, they put the speaker out on the porch on Christmas Eve, and I would play Christmas carols, and people would drive up and down the street and listen to the music.

By then you could harmonize your notes into chords?

Oh, sure. It took me a long time before I really learned to read notes well because it came so easily by ear. Do you play by ear?

Yes, I haven’t learned to read [notes] yet. It seems hard. I’ve taken some swings at it but I haven’t really learned. What gave you the sensitivity, the empathy that you have with children? What gave you the desire to help them feel strong and powerful?

Maybe being an only child for eleven years. Your antennae go out pretty far in trying to sense how other people are feeling. My sister didn’t come along until I was eleven. I don’t know; I’m sure some of it is biological. My parents were very much concerned about others. They were very active in their church. Both Mother and Dad were elders in the first Presbyterian Church of Latrobe for many years. I remember during the Second World War, my mother was in charge of the whole area’s volunteer surgical dressing department. I understand that in World War I she helped make sweaters for soldiers. She was a great sweater maker. She made all my sweaters.

Every year we would open these boxes and here would be this wonderful sweater, and mother would say, ‘Now what kind does everybody want next year?’ … She’d say, ‘I know what kind you want, Freddy. You want the one with the zipper up the front.’ And that’s what she made.

Including the famous one?

Yeah. Every month she would make a sweater. So at Christmas time, twelve of us in our extended family got a sweater each year that was made by Nancy Rogers. Every year we would open these boxes and here would be this wonderful sweater, and Mother would say, “Now what kind does everybody want next year?” She had all these patterns, you know. She’d say, “I know what kind you want, Freddy. You want the one with the zipper up the front.” And that’s what she made. The one that’s in the Smithsonian is one that she had made.

How did you land in the fast lane in New York in the early days of television?

Well, I had just gotten a music degree from Rollins College. I was a composition major. When I decided I wanted to do television and got a job at NBC in New York, they noticed I had a degree in music so they assigned me to various music programs. What a wonderful experience that was! The Hit Parade, The Kate Smith Hour, The Voice of Firestone, The NBC Opera Theater...those were all programs that I was intimately associated with.

What did you do on a show like The Lucky Strike Hit Parade?

I was a floor manager. Now, that was a huge program. We had five floor managers. I had earphones on, and I was connected to the television director who was in a booth. And the director was telling me what is coming up next and to get it ready. Then you ask the stagehands to move things and get them prepared for the next scene. And you also ask the talent to get into place and you tell them how long they have until the next scene is about to start. I remember Snooky Lanson, one of the stars, so well. Do you know who I mean?

No.

He was one of the stars. There was Dorothy Collins, and June Valley, and Russell Arms, and Snooky Lanson. They were the stars during my two years. Anyway, Mr. Lanson loved to play craps backstage with the stagehands. I’d go back there and say (whispers) “Mr. Lanson, you’re ON in two minutes.” He’d say, “Be right there, Freddy.” And so he’d come out and get in place and it was as if he’d been right there all evening. It was just amazing what could be done in the days of live television. We started rehearsing early in the morning and by nine o’clock at night it was ready to go on the air. The NBC Opera Theater was what I really loved. We did the first Amahl and the Night Visitors. It was commissioned for that program. I remember Toscanini coming to the dress rehearsal, and after he just hugged Gian Carlo Menotti [the composer] and said in Italian, “It’s the best you’ve ever done!” Here I was. How did I know I was right in the middle of history being made?

Did you have any sense of that?

No. In fact, I would go home and tell JoAnne—we were married when I was in New York, in the second of those two years—I didn’t know anything about famous people, except Menotti. I remember one day saying, “Oh, Sarah”—I usually call her Sarah—“there was this WONDERFUL singer. She really is going to go far. Her name is Peggy Lee.” Sarah said, “Fred, she already has gone far.” But these were people I was floor managing. I was hearing wonderful music.

Did you, as a musician yourself, want to write pop songs in those days?

Oh, yes. In fact, I’d think, “Here you are, right in Tin Pan Alley, and you’re managing other people’s music.” Once when I was in college some people I knew got me introduced to Jack Lawrence. He was one of the biggest songwriters in New York. He wrote If I Didn’t Care and a lot of other songs. He was like Irving Berlin, that big. I went to visit him when I was a freshman. And I had five songs. I went to his brownstone. He was very welcoming. He asked me to play my songs, and I did. He listened, and he said, “Those songs have a lot of promise, Fred. How many more do you have?” I said, “A few.” He said, “Well, to me a few means three, so that makes eight. I’d like you to come back when you have a barrel full.” I was crestfallen. I was sure my five songs would end up on Broadway. But that was some of the best advice I ever got.

Don’t ever think of any one composition as so precious that it has to define you.

It seems contrary to what you hear now. Everyone says, “Only bring a publisher or an agent your best song” or “only bring a few.”

I can understand that if you have already written your barrel full. He was telling me to write, write, write. It was excellent advice. The more I wrote the more I saw the possibility of writing. I don’t know that I would ever have written these little operas for the Neighborhood if I hadn’t gotten that advice then. In other words, “Don’t ever think of any one composition as so precious that it has to define you.”

So did you ever go back with your barrel full?

I did, when I was already doing my Neighborhood programs. He had heard them on television.

I think one of the greatest gifts you can give anybody is the gift of your honest self.

Have you ever formally studied the role of music in child development, or what characteristics of songs seem to appeal to children?

I used to take my puppets to the center where I did my practicum work in child development. I would show the children the puppets and talk for them and play music for them to dance or move to, or to make up words to. I rarely played ordinary nursery rhyme songs. I loved in front of them what I loved to do; that is, to make the puppets talk and play the piano. I think one of the greatest gifts you can give anybody is the gift of your honest self. The woman who was the director of that nursery school told me that she had never seen the children use puppets, and there were puppets all around. She said they used them imaginatively when I would come with my puppets. She made an analogy to a father of one of the children several years before. He was a sculptor. He would come to the school once a week just to fashion clay in the midst of the children, not to teach sculpting, but to show how you enjoy it in front of the children. He would come and love that clay in front of the children one day a week. She said that never before or since had the children used clay so imaginatively as when that man used to come and love it in front of them. Nothing didactic about it.

Just loving what you love in front of them...

Yes. They will catch your enthusiasm. Attitudes are caught, they’re not taught.

As you say that, I think about what I love to do, and whether that’s my experience. It’s almost Zen-like. With music, if I’m singing a song or making one up with children, if I become too conscious of the process or the time, it’s distracting and we lose each other. I think tension is caught as well. But I think when I’m having fun, they’re having fun. We’re all having fun.

So you caught my notion...

Doing puppets or playing the piano or making up songs isn’t for everybody, but it’s like drinking water or breathing fresh air for me.

Why is music so important to your neighborhood?

Because it’s essential to me. Doing puppets or playing the piano or making up songs isn’t for everybody, but it’s like drinking water or breathing fresh air for me. And Neighborhood would certainly be different if I weren’t in it. And it would be fake if it didn’t have a large musical component.

One of the things I love about your music is the jazz piano. Is it improvised?

I write the songs, and then Johnny Costa, a magnificent jazz pianist, improvises much of the music around them.

You use opera in your neighborhood. I’ve never heard that in children’s entertainment except maybe with Mighty Mouse.

I’ve written about thirteen operas of about twenty minutes each. The Grandparent’s Opera was one of them.

Do you keep up with children’s music? Are you aware of the artists that are out there now?

I do not. I just give to children what I find within me. I don’t watch much television at all, either. I’m a reader. We haven’t used television well at all in this world. It’s a perfectly wonderful medium. There have been times when it’s been used beautifully. But it’s been so misused that it bothers me.

We’re still one of the islands that encourage quiet and some space to think.

Life and TV are noisier and more action oriented now than when you started working. Has this affected your show?

We’re still one of the islands that encourage quiet and some space to think. We hear every day from people saying how grateful they are for some time of calm. Now, I think people should have complete silence every day.

I just get so annoyed when I’m out somewhere and I can’t close my ears the way I can close my eyes. We’re bombarded from every direction. Who says that people want to hear what’s broadcast in public?

I know what you mean. Our children do watch TV. We regulate how much and what they can see, but we let them watch. Our younger daughter, who is almost five, feels a lot of pressure at school to react to the Power Rangers and other faster, noisier shows.

I agree. My grandson has been sucked into that too. He watches the Power Rangers. But he still watches the Neighborhood. I just lament the fact that children watch so much. Too much. They need time to play.

Has all of this affected either how many children watch the Neighborhood or the age at which they leave you?

We used to think that the target age was five or six, and that we might have some four-year-olds and seven-year-olds. Now we’re hearing that the children are starting to watch at eighteen months. The high point is about three. It’s ridiculous. What’s that doing to their psyche? I’m not concerned about what they might see on the Neighborhood, but I am concerned about what they might see all around it. Some children watch unmonitored and see shows meant for adults.

All I can do is be myself…. So I just pass on what’s been given to me.

What is it like to be the remaining island of calm in a rising sea? Do you ever stand up there in front of the camera and feel like you’ve got to be a lot for a lot of people?

All I can do is be myself. I’ve had the grace to be able to do that. I walk into the studio and I think, “Let some word that is heard be Thine.” Whatever doesn’t come from the eternal is just dross anyway. So I just pass on what’s been given to me.

Do you ever have visions as you look at the camera of the horrible situations some children are in as they look back at you?

Oh yes. Not that I have any exact view of it, but I think about the children and some of the ones I’ve known in desperate straits. I’ve been to a lot of places, some of them very poor. I know I can’t do everything, but I know I can give the kind of nourishment that comes from an understanding of the development of the human personality.

Do you have a sense of the importance of being one of the only widely visible males that works with and cares about young children? Do you see yourself as a role model for maleness?

I remember one time after the Neighborhood had been on quite a while, the people in New York asked me to come talk about doing some commercial television. One of the first questions they asked me was “What costume will you wear?” They said, “You’ve got to jazz up what you do.” I said, “Well, it looks to me as if this meeting is over,” because for all the time I’ve been on television all I’ve ever wanted to do was to give one more honest adult to the children who are watching. Covering me up with all kinds of jazzy stuff is not my idea of the expression of honesty. Does that answer your question?

Part of it. I still want to ask about maleness. One reason many people appreciate you is that you give a child a chance to see a man on television who is not loud, or fast in his movements, or always in an action mode. To what extent is that just you, and to what extent do you see yourself as a role model?

I think that if I were very aggressive in my movements and my speech that it would be a sham for me to try to act like Mr. Rogers. We got a letter yesterday in which someone said how grateful they were that a certain person was on television who was close to being “Mr. Rogers-esque.” It seems to have become part of the culture: that a gentle, calm, quiet male can be considered “Mr. Rogers-esque.” I just don’t think you can fake that. I wouldn’t want to advise someone who is just the opposite of me to do it just like me. It wouldn’t be real. I think children and adults long to be in touch with what’s real. Don’t you?

I do, and I think people “catch” realness just as they catch the love one has for the things one does.

That’s a beautiful analogy, picking up on what we talked about before.

Has your being a minister affected the Neighborhood, or your work with children?

It has helped me become who I am, and it’s all a part of me. My relationship with my Creator is just part of who I am. I don’t think you have to use labels to allow people to see what is your inspiration.

You’ve been working with children for four decades now. Would you have any advice for those of us who are just now choosing to spend a good bit of our time and our creative energy working with children?

(Long silence) First of all, I would think that it would be important to understand the roots of your desire to do that. As you come to understand that, then you can understand what might be in the children with whom you’re communicating. With parents, for example, as a child goes through certain stages of development, that re-evokes those feelings in their parents that stem from those same stages that they went through. I think that way you get to be more gentle with yourself, and as you’re able to do that, then the children that you’re with sense that you’re accepting of them, as you become more accepting of who you have been as a child, that child that you continue to carry along with you in life.

Originally published in Issue #19/20, Summer 1995.