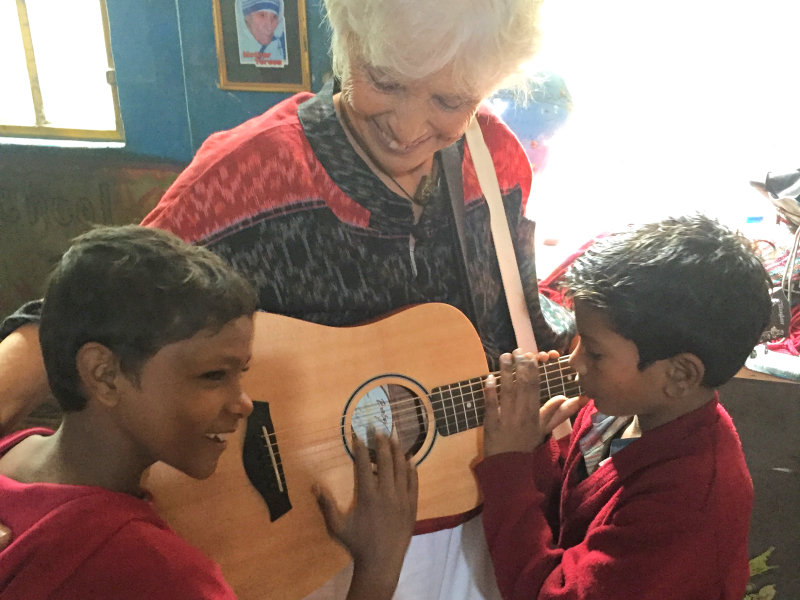

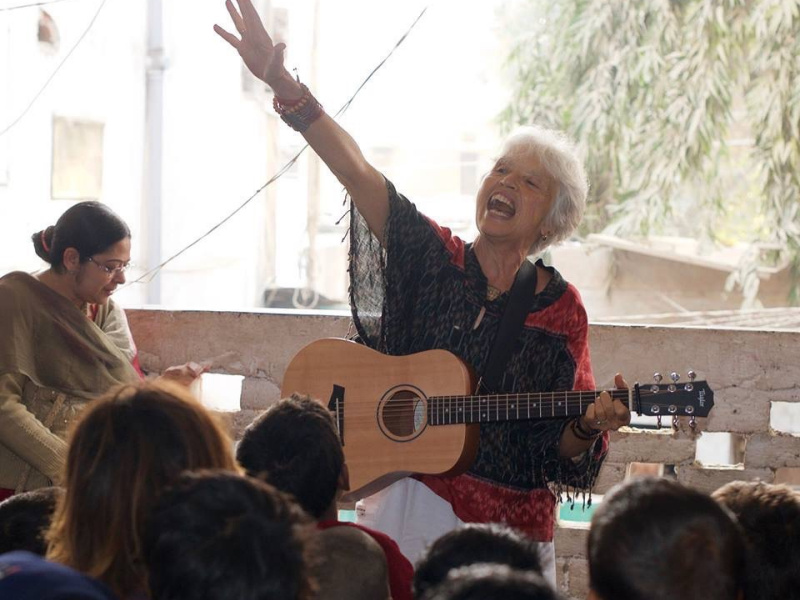

Singing with street children in Sarnath, India, at Buddha’s Smile School

Singing with street children in Sarnath, India, at Buddha’s Smile School

A Musical Pilgrimage

Six Countries, Eight Months, and a Song

by Betsy Rose

Introduction

In 2015–16, I went on a solo musical pilgrimage to six countries in Asia and Africa, singing with children, women, and human rights workers. It was part sabbatical, part midlife reboot, and part mission to learn how our special brand of children’s music and community singing can open doors and hearts in other countries, building bridges across all kinds of differences.

We all know that song is a natural connector, heart opener, and friend-maker. Could it transcend language and cultural differences? Could it be a vehicle for learning, discovery, and friendship? The answer is a resounding YES!

Buddha’s Smile School, Sarnath, India

Buddha’s Smile School, Sarnath, India

On a personal level, I hoped to examine some of my own Western perspectives and subconscious assumptions, shake myself up a bit in the service of returning with a wider and deeper understanding of my own and others’ humanity. In a shrinking planet where our very survival depends on knowing, understanding, and working together globally, a United States–centric worldview is ineffective, limited, and even destructive. I was hungry to pop that bubble and be changed.

Any of you could do what I did—and you would be welcomed with open arms in the communities I was blessed to visit. I hope this report will be helpful in your musical work, wherever you find yourself.

Why, How, and Where's the Money?

Why

In 2014, I was sixty-four years old, my parents were gone, my only son was off in college, and I had my partner’s support for whatever direction I chose to take. I was unencumbered and free to listen to a “still small voice” within, one that other responsibilities had drowned out for years. I’d been working with children and in social justice “artivism” for many decades, and while the work was worthy and wonderful, I personally felt hungry for a new “growing edge”— something fresh and new in my musical and public life.

How

It helps to have been singing and otherwise being a public presence for forty years! Being deeply involved in Buddhist practice and communities, my connections in Asia, especially Thailand, abounded. Friends and associates in the United States are people who tend to have travelled internationally—as volunteers, members of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), funders, spiritual pilgrims, or just adventurers—and they know people who are doing great work in developing countries.

Once I announced my plans and where I thought I’d be going, contacts flooded in.

“Oh, I know a great project for girls in Kathmandu.”

“My daughter volunteered at a school for street kids in Varanasi, India.”

“I’ll connect you to a Buddhist monk in Thailand who has helped start several schools for youth founded on Buddhist values.”

It was almost overwhelming! And one contact led to another.

Where’s the Money?

Personal funds for this venture were nonexistent. It did not fit my vision to pursue compensation by singing in private middle and upper class schools and settings. I went back to my inner voice, this time with a request: “Okay, Spirit, if I’m supposed to do this, you find me the money.”

I learned that my alma mater, Wellesley College, had an alumnae travel fellowship. Now, in my limited worldview, lefty/progressive feminist folk artists weren’t generally fellowship material (no published books, not Dean of Academic Department, not head of an NGO), but the whole venture was so touched by improbability and imagining the unimaginable that I went ahead. I wrote the proposal while caring for my dying mom, which practically tore my brain in two, alternating between heart-centered, emotional care for her body and spirit, and left brain detailing of itinerary, budget, mission, resume, and more. “This is a terrible application,” I thought over and over as I ran from computer to bedside and back. “It’s completely mediocre and I won’t get the Fellowship anyway. Give up. Focus on mom, and forget the Fellowship.”

But that dogged inner voice said, “No way! Go ahead and submit it. Let THEM decide whether or not you’re a viable candidate.”

I was the most surprised person in the world when I learned I was one of the three chosen grantees! I could write a whole other article about this experience, but here and now I want only to say that if you have a big dream to travel and sing in the outside world, don’t narrow your thinking about finances. There are so many ways to find funds through social networks, your professional fan base, family, small foundations, crowdsourcing, obscure fellowships, and more. My lesson was this: If there’s a deep inner call, and the Universe wants it, your dream will come together. Have faith, be bold, forge ahead, and see what opens up.

The Journey

My pilgrimage began in Thailand, where I spent a month singing in Buddhist-based private academic schools, retreating in a historic Thai Forest Tradition monastery and several other retreat centers. After a family visit in Australia and a short swing through Bali (singing at a midwifery center and a “green” school), I was on to India for a month. Main stops were Ranchi (in the new state of Jharkhand, a largely tribal area), Bodh Gaya (where the Buddha sat under the Bodhi tree and was enlightened), Sarnath (another historic Buddhist site), Delhi, and Dharamsala (home of the Dalai Lama and the exile Tibetan community). After that, I spent six weeks in Nepal, splitting my time between Kathmandu and Pokhara, the latter being a popular launch point for trekkers. In spite of a sprained ankle, I did “jeep trek” to the Mustang region, the Annapurna region, and very near Tibet.

Schoolgirls in Pokhara, Nepal participate in Wall of Hope violence prevention campaign

Schoolgirls in Pokhara, Nepal participate in Wall of Hope violence prevention campaign

From Kathmandu I flew to Paris (whole other article there about culture shock), walked parts of El Camino de Santiago—an ancient Christian pilgrimage—in France and Spain, and enjoyed some family visits from my son in the Netherlands and my sister in Ireland. This was personal time, not covered by the Fellowship.

My final adventure took me to Kenya, where I spent wonderful and very heart-opening time working with an organization that supports women exiting prostitution and abuse. In Liberia, I spent precious days with village women who were part of the dramatic peace movement that stopped a bloody civil war in 2004, and are still actively working on nonviolence in their country. This is a little known and incredible story. I recommend viewing the riveting documentary Pray The Devil Back To Hell, which explores how a narcissistic, violent dictator was peacefully overthrown.

With the foundation of a few contacts in each country, it took very little time for the grapevine to kick in. Word of mouth and social connecting is a deep part of most of the cultures I visited. So I had no lack of opportunities to sing and share and learn and fall in love with the amazing people I met.

Crossing the language barrier, discovering or inventing ways to connect with children in challenging situations, and getting some perspective on what was actually useful and appropriate in these very new settings were vital tools I needed to fulfill my mission.

Language

Language is at the heart of a song, and a staple of my children’s music repertoire is “zipper songs” where children add their own words to a preexisting song form. How much English would these children know, or, if singing in their own language, how could I guide them to find syllables that fit the beat? Songwriting with young people is a challenge right here at home. What would work in Hindi, Nepalese, and Thai??

Before leaving, I worked with translators, selecting about eight songs for young people and for women from my “A list” of tried and true favorites. My criteria were that songs were short, simple, singable, and not too many words, e.g., “This Little Light of Mine,” “We Shall Overcome” and “May You Be Happy” from my CD, Calm Down Boogie.

A small group of wonderful Bay Area women translated these songs into Hindi, Nepalese, and Thai. They were not musicians, so the process was twofold. First, they made a literal translation, and second, I’d try singing their words and we would alter and modify them to fit the rhythm. The results turned out very well when field tested; the hardest part for me was wrapping my tongue around the unfamiliar languages while leading the group and playing guitar. But this turned into a wonderful chance for the children to teach ME, and for me to be the bumbling learner.

Leveling—Lifting Them, Lowering Me

As time went on I found more and more ways to be the learner, to “level” the ground between us a bit, to pop the bubble of prestige and privilege that surrounded me. Here’s a quick digest of leveling activities I discovered:

Silly Self–Deprecation With Both Adults and Children

I found ways to make fun of myself, nonverbally—to be clumsy, to use body language, to be playful, to make exaggerated gestures and facial expressions—so the children couldn’t help but laugh at me (not something you are supposed to do to an honored guest!). One example: In a tribal government school in Ranchi, India, a large group of shy, curious children sat on the courtyard ground as I was introduced with much pomp and solemnity (“This is an important person, children; you be good”). The front row of small girls would look at me, then hide their eyes and giggle, then look again, and repeat. Why are they giggling, I wondered? It occurred to me that perhaps I was the first white person to visit them for more than a governmental or NGO look-see. I was actually going to interact with them! Instinct kicked in, and I proceeded to do exactly what they were doing: look at them, then hide my face and giggle, then look again, and repeat. This broke the ice; I was no longer playing the role of distinguished guest!

Find a Way for Them to Teach Me

In Nepal, there is a universally known folk song, “Resham Firiri,” and after hearing it sung by street musicians, in cafés, by a traditional instrument band, and on the radio, I HAD to learn it. When I met a new group and wasn’t quite sure how to connect, I would start singing it. Faces lit up in smiles, hands clapped, voices carried the song along, and we were off and singing! The looks they exchanged with each other as I started to sing said to me, “She likes our music! She’s one of us!” The song has many lines that I never could wrap my tongue around, so I would ask them to coach me, break it down, and repeat with me. They instantly became the teachers, and this role reversal was key to the magic of whatever happened next.

Prop: Guitar as Sidekick!

How many of you use props like puppets and stuffed animals to widen the scope of personalities onstage? My prop was my guitar. I played many games involving the guitar, having the children guess what was in the case and suggesting silly options—an elephant? a snake?—before dramatically revealing the long-awaited guitar. She had a voice, and said “hello” to them through a quick, loud guitar riff or a silvery harmonic twang high on the neck, and I invited the children to greet her in THEIR language, which led to a simple improvised “hello” song in several languages.

Gifts, or Coals to Newcastle?

The countries I visited have highly developed musical cultures, with strong dance and song traditions that are an integral part of their family, community, and religious life. Wherever I visited, I was greeted ceremonially with song and dance. I wondered, what on earth was I doing bringing songs to Africa, the source and birthplace of the communal, collective, oral tradition music-making I have gratefully drawn on for much of my work? But I learned that there were more nuanced, unexpected ways that my music enriched their lives.

The Gift of Participation and Play

Public schools (called Government Schools) in India and Nepal are modeled after the traditional British educational style where teachers talk and children repeat or take notes—in other words, rote learning and repetition.

Government School, Ranchi, India

Government School, Ranchi, India

The teachers I observed were often unsmiling and severe. The atmosphere was serious and controlled. So when I arrived on the scene, using exaggerated body language, hand clapping, and call and response games, and then launching into a song in their language, the children were at first bemused, then delighted, then raucous and fully involved. This was not their usual school day activity!

With the very young there was no real shared language, which allowed me to become more extroverted, funny, silly, and bold than I have ever been in the United States. It is a wonderful gift to have to constantly improvise. And yet the core musical skills remain and DO translate completely. How many of us have found that clapping rhythm patterns and asking the audience to echo them is a foolproof starter to an assembly or concert? How many of us have learned how to “change it up” suddenly? To go from loud and funny to quiet and whisperingly confidential, intuitively feeling what will keep the youth on their toes, not knowing what to expect next? These were invaluable skills that came with me in my tool bag.

Creative participation is not—in the government schools I visited—a value. Education was serious work, and fun was not part of preparing to function in a world economy. This made zipper songs challenging, and I learned that soliciting new words and ideas from the students (upper elementary through high school, who had a working knowledge of English) took some time and coaching. It made me realize how most young people in the United States are raised in a culture of participation, where the individual’s ideas and input are valued, and creativity and innovation are encouraged. I’ve found children in the United States, unless traumatized or otherwise shut down, assume their voices, their ideas, and even their feelings are of value and interest to the group.

Government School, Ranchi, India

Government School, Ranchi, India

The Indian and Nepalese public educational systems focus on absorbing and storing knowledge. Students are taught to listen to and respect authority, learn one’s place in the system, and be a cohesive part of a group without disrupting or standing out. But there is a hidden gift within these communal cultures where the group has a higher value than individual identity and agency. I experienced a genuine sense of caring for and being responsible to each other, of putting the group before the individual. This experience was precious beyond words and forever changed how I see our culture; it revealed the isolation and insulation, competitiveness, and self-centeredness that are often the by-products of individualism and capitalist democracy. Every culture is “a package deal,” and as the deficits of our own became more tangible to me, the gifts of our global south neighbors came beautifully into focus.

The Gift of Focusing on Girls’ Education and Empowerment

The “Girls Be Strong” song-video project was key to my connection with girls. Before leaving the United States, I wrote an exuberant a cappella song (published in this issue) about girls’ capacities and dreams, and secured a small grant to support the filming and editing of a music video. In the communities, schools, and projects I visited, we would sing and learn the song in English, and I engaged them in a songwriting process to add a verse from their cultural perspective. What are girls’ dreams in a village in India? In a slum in Nepal?

Why are girls’ educational opportunities still so limited in parts of Asia and Africa? Economics, combined with traditional and long-held cultural beliefs and practices, are at the heart of it. Even government education costs money. Uniforms are universally required and worn in all but the poorest schools, and books and materials must be paid for, often along with a small tuition fee. This puts tremendous pressure on poor families and has a number of oppressive results for women and girls.

If money is scarce, tuition money will go toward the boys in the family. Their education comes first, and an educated male has much more access to a better-paying job than an educated female. The family will rely on the earnings of their grown child(ren), so educating the boy is a practical family investment. It is assumed, at least in rural or tribal areas, that a girl will marry young—child brides are still not uncommon—and bear many children. She will go live with her husband’s family. Why invest in education for a young mother who is leaving home anyway?

Another tragic consequence of school costs is that some impoverished mothers turn to prostitution to supplement the family income in order to educate their children. And when poverty is grinding and inescapable in a family, a girl child may be sold into sexual slavery so that other children can be fed. I saw firsthand how poverty is a women’s issue, how violence against women and trafficking are direct products of poverty, and that just as girls and women are the primary victims of male warfare, the same is true of economic oppression. The passion for girls’ education that I saw in my travels reflected a growing understanding that the country as a whole could not progress while women remained impoverished and uneducated. Listen to Nunu from Liberia, and the YUWA schoolgirls in India, as they speak their passion and determination to break out of traditional limitations in the “Girls Be Strong” video.

Other Gifts

Presence

A Westerner interested enough to visit, especially in poor or tribal communities, means a lot. The key is to be present and respectful, and engage in fun and interaction. By reaching out to those you meet with warmth, humor, and humility, you implicitly honor them in their world.

Girls who sang in the "Girls Be Strong" video, posed in front of a mural created for the Wall of Hope violence prevention campaign, Fairyland School, Kathmandu, Nepal

Girls who sang in the "Girls Be Strong" video, posed in front of a mural created for the Wall of Hope violence prevention campaign, Fairyland School, Kathmandu, Nepal

Musical messages of empowerment

Several of the songs I brought expressed messages of empowerment, dignity, hope, and future possibilities for girls, children, and women. “We Shall Overcome” is widely known, especially in India and Nepal where the tradition of Gandhi looms large, and is core to India’s own story of liberation from British colonial oppression. And when I launched into it in their language, barriers between us fell in an instant. Faces lit up and voices soared as this white-skinned, elder stranger started in with “Ham Hunge Kamiyab” (“We Shall Overcome” in Hindi, India’s official language).

“We Shall Overcome” became one of my go-to, never-fail songs, and unexpectedly became a vehicle for the ongoing work of “leveling.” Creative group songwriting, where we added new verses to a familiar tune, was new to them, and I could feel the lifting of spirit and brightening of heart as they made and sang new verses: “Girls will not give up…” “Boys support the girls…” “Women’s power is rising…” “We can change the world….” The message of overcoming, in the context of poverty, low sense of possibilities, idealization of the West, earthquake impact, war, disease, and oppression of girls and women conveyed a core message that “people like you HAVE changed history. You are a future world changer.” Street kids, village girls and women, former prostitutes, developing women leaders, all loved singing and making new verses.

In India and Nepal the song allowed me to share with young people (and sometimes adults) the story of Gandhi’s profound impact on Martin Luther King, Jr., and to thank them for helping us in our struggle for equality. And in Africa, more poignantly and painfully, I found myself telling Kenyan and Liberian youth a much-abridged story of how slavery brought African people to our country, and how our current wealth and advanced economy and society is due to centuries of unpaid slave labor that built our economy. I shared that the songs created by African slaves became the music that fueled our own songs of freedom. I found myself expressing deep sorrow and regret, on behalf of my country, for this shameful history. While many students learn the history of the worldwide slave trade, I’m not sure they had ever heard someone link current American privilege and success to it. Their faces were solemn, eyes wide, listening deeply. I’ll never know what impact this all had, but it felt real and right to me in the moment.

Teaching English through song

I stumbled on an additional gift that singing offered: assisting English learners in developing language skills. Singing slows everything down and extends words and syllables, so the tongue and mouth feel the shape of syllables and the subtleties of pronunciation. For example, there is no “sh” sound in Nepalese, so “We shall overcome” came out as “We sall overcome.” I quickly improvised ways to practice the “sh” sound, and of course, the repetition of the verses and choruses gave singers many opportunities to practice without it feeling like a drill.

And Now—the Big Lesson(s)

Entering into so many unfamiliar communities and unexpected situations kept me off balance in an uncomfortable and delightful way. Asia does not run on the same clock and calendar paradigm that Westerners rely on. I found that plans changed in a wink and start times were vague suggestions, often easily delayed. Flexibility and faith became my guiding practices. I had to trust my heart and my intuition, because they were all I really had. Whatever plan I thought I had was often unrelated to what actually unfolded in real time.

My favorite example of this occurred at a middle-class K-12 private school in Delhi, one of the very few I encountered. After a day of working and singing with the students, I was invited back for a teacher training the next day.

I asked, “Will these be teachers who saw my program today?”

The administrator answered, “Oh yes.”

“Mostly primary school teachers?”

“Yes.”

“So they want to learn more about how I bring music and song and mindfulness to children?”

“Yes.”

As we drove to the campus the next morning, I asked again,

“Who are the teachers I’ll be working with, and how many?”

The administrator answered, “Well, these will be college professors, probably about a hundred.”

Gulp. Shift gears. Don’t panic!

“And what is it you would like me to teach them?”

“Well, they struggle a lot with stress. Could you teach something about mindfulness and stress?”

This was five minutes out from the start of the program.

I have experience teaching mindfulness and have worked with adults, but this was so unexpected that I felt the ground drop out from under me. But as a good guest and presenter, I smiled and said, “Of course, I’d be happy to.”

But it didn’t end there.

The program began with a formal welcome and introduction of me (the honored guest thing, again), and as the gentleman at the podium, whom I had never met, began listing my accomplishments and history—mindfulness, education, children—my thoughts drifted away but were jerked back by these words: ”Her life as a former model in Italy, and her connections with the Italian mafia….” My host and I exchanged horrified glances, and together we shouted “No! No! No!” Much laughter, much embarrassment, and the speaker quitted the stage in disarray. And then, there I was in front of the mostly male, mostly engineering faculty, with nothing but my breath and a prayer to guide me. And I had a blast! And so did they! Intuition and faith carried me far beyond where planning and preparation could have gone and created a more lively, authentic program.

Buddha’s Smile schoolchildren, Sarnath, India

Buddha’s Smile schoolchildren, Sarnath, India

My Main Mistake

It took me a while to grasp the reality of how language and cultural differences required a change of approach in teaching songs or hand and body motions. My two main course corrections were to simplify and “dial back.” Many children I sang with were street or beggar kids who had little or no structure to their “home” life. Traumatized and unregulated in various ways, they couldn’t concentrate easily on anything complex. Those of you who work with children in similar conditions (homelessness, foster care, abuse, etc.) have undoubtedly found this to be true as well. When I felt children stumbling, or noticed they were lost or not fully engaged, I would dial back and break the song or activity into much smaller units of learning. I’d go through a phrase or motion several times. If I started a program with song, and it wasn’t connecting, I’d shift to hand clapping patterns the group echoed with lots of motion and some silliness to get everyone on board. Then on to more complex activities.

What Now?

I hope my experience whets your appetite for musical adventure outside of your familiar world. We children’s artists are uniquely suited for cross-cultural friendship! Working with children, anywhere in the world, inspires playfulness, flexibility, openness, invention, curiosity, and letting go of agendas and plans. It involves tuning in and sensing what is needed in the moment. These are the necessary skills for crossing any borders, including in our own country.

I'm happy to share my resources with you, be it international contacts, translation resources, funding ideas, or anything else. CMN member Stuart Stotts is also versed in this transnational music making, and between us and others, perhaps a CMN international brigade of Global Troubadours can be prepared and launched into a world that is more welcoming, more friendly, and has more to give back than I ever could have imagined.

We are needed, we are gifted in special ways, and there is much to do!

You can find more videos from my travels on my YouTube channel.