Over the years in CMN, there would be stretches of time when it seemed like we were having daily amusing conversations on the email list about kids appearing at our concerts or in our classrooms with unusual (read: challenging) behavior that often required us to figure out mid-song how to negotiate some kind of interruption. We would share these anecdotes with a smile and a laugh and a shake of our heads, always walking that tightrope of caring about the children and hoping that we had handled a situation in such a way that no one got their feelings hurt or had a bad experience, and lamenting why we had to be shepherding this kind of behavior and where were the parents/teachers/guardians.

As both a performer and a teacher, I always found myself in an interesting place, because I have a son with autism. I often experienced these interruptions with the knowledge that the child creating them was behaving much like my own son might. I’d challenge myself to handle the situation with the compassion and care I wanted people to offer my son. Because of my home experience, I also had some insight into what might be behind the behaviors.

My son was my first introduction to sensory processing disorder (SPD), as most people with autism also have SPD. Having taken a deep dive in educating myself about this phenomenon, I discovered not only how to help my son but also how to help many of my students who had unusual behavior, though they were not diagnosed with any kind of specific disability. All this led me to understand more about the invisible barriers to learning that so many of our students grapple with.

SPD has been talked about since the 1970s, when the name was coined by occupational therapist and psychologist Anna Jean Ayres. In 1998, Carol Stock Kranowitz, MA, expanded upon it in her book The Out-of-Sync Child. The condition is still largely unheard of among people working with young children, and even those who have heard of it don’t necessarily know how to identify it when they see it.

But SPD is not at all uncommon. The National Institutes of Health published a study in 2017 with the latest research, stating “Current estimates indicate that 5% to 16.5% of the general population have symptoms associated with sensory processing challenges” (Miller et al. 2017). And it explains a lot of the behavior that we see in our concerts and our classrooms.

Many children are born with SPD, but many more develop symptoms of SPD as a result of adverse childhood experiences (ACES), also known as trauma. Unfortunately, huge numbers of children in our world today struggle with the effects of trauma. According to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, “Among U.S. adults from all 50 states and the District of Columbia surveyed during 2011–2020, approximately 66% reported at least one ACE, while 16% reported four of more ACEs” (Swedo et al. 2023).

Many of the children who are struggling with the effects of trauma will show up in our spaces with behavior caused by sensory overload or shutdown. Generally, we do not notice the children who shut down because they likely sit quietly, not causing any kind of disruption. We notice the children with sensory overload, who make their presence known and demand we take care of whatever need they have at the moment.

More and more children in our world are dealing with a broad variety of neurological challenges and flat-out trauma that directly affect their ability to be comfortable in community spaces. The absolute best thing we can do when faced with sensory behavior is not be upset by it—even in cases where that requires sainthood—or shame the child (or their parent!) in any way. But there are more specific strategies that can help. Having a little bit of understanding of what might be causing the challenging behaviors allows us to respond in the moment with compassion and support.

Here are some general categories of SPD we might see for children with hypo-sensitivities and hyper-sensitivities, along with typical behaviors and supports. Sometimes supports for both behaviors overlap.

Auditory Sensitivity

Hypo-sensitive: This child will not cause any trouble, but they also will likely not be participating, because all the noise around them becomes incomprehensible soup. It’s too hard to follow what is going on, so they tend to just zone out. They may zone back in at random moments and want to participate but be out of sync with what the group is doing.

To help hypo-sensitive kids: In a classroom or concert setting, they almost need a translator to keep them grounded.

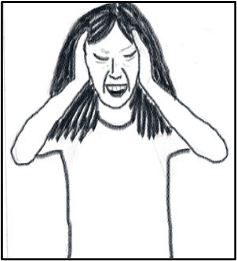

Hyper-sensitive: This child might come into our music space yelling, “It’s too loud!” They do not hear that they are being loud and are not aware that they might be bothering other people with their volume. They just know that they are bothered by loud noises. They may also be very afraid coming into a concert space because they instinctively know that loud concert spaces are hard for them.

To help hyper-sensitive kids: Invite them to be your sound engineer—ask them to tell you what volume feels okay. By doing this, you not only notice and acknowledge them, but you also help them learn to pay attention to their own needs and verbalize what is uncomfortable for them. This often helps to reduce their fear of loud spaces.

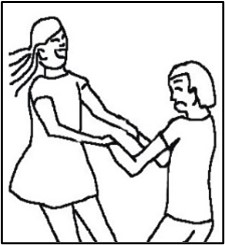

Tactile Sensitivity

Hypo-sensitive: This child wants to touch everything and everyone; that is how they feel grounded and safe. They may not be paying attention to what is happening around them as they are more focused on touching everything. Try to make sure they are not setting next to the child who is afraid to be touched!

To help hypo-sensitive kids: Fidgets are wonderful. Something that keeps their hands busy also helps them stay focused. But they have to hold on to them, not throw them across the room.

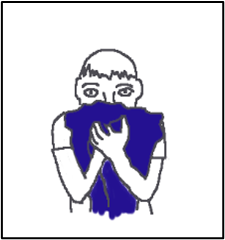

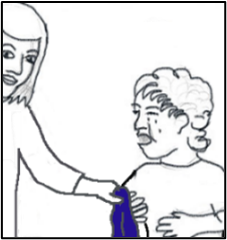

Hyper-sensitive: This child does not like to be touched. They may be afraid to be in a crowded space because of potentially being touched unexpectedly. They may not want to get up to dance or participate in any way because they don’t want to be touched.

To help hyper-sensitive kids: Give them a space off to the side, not in the middle of the crowd—somewhere with breathing space.

Olfactory Sensitivity

Hypo-sensitive: This child wants to smell everything, because that is how they feel more grounded and safe. They may be trying to smell other children’s hair, etc., and other children may not be happy about that.

To help hypo-sensitive kids: A sachet with the scent of their choosing is ideal.

Hyper-sensitive: This child might come into our music space complaining that things stink. They have an over-sensitive sense of smell, and not only can they smell everything, many things smell bad to them and make them nauseous.

To help hyper-sensitive kids: Same thing—a sachet with the scent of their choosing!

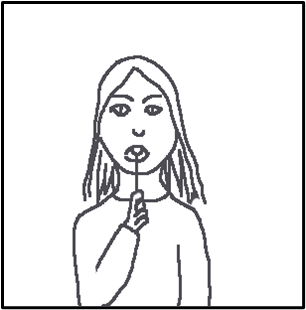

Oral Sensitivity

Hypo-sensitive: This is the kid who puts everything in their mouth. Like the one who wants to touch or smell everything, this child focuses best when their mouth is active, so they may be chewing on their fingers or their clothes, or a prop that we have handed them.

To help hypo-sensitive kids: Sucking on hard candy keeps their mouths busy. “Chewelry” is a newish item for these children. Chewing gum can work where it is appropriate.

Hyper-sensitive: This child is a very picky eater, but also may be averse to playing wind instruments. Because they may not have eaten enough at breakfast or lunch time, they may be hangry by the time they get to our classroom or performance.

To help hyper-sensitive kids: Same thing—hard candy! It is generally outside our scope of responsibility to get them fed, but if we have connections with the classroom teachers, we can discuss what strategies are being explored that might help their participation.

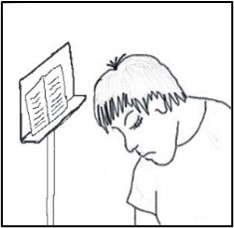

Visual Sensitivity

Hypo-sensitive: This child may hyper-focus visually on unusual things because that actually helps them listen better. But what they are hyper-focusing on is often not what we are trying to show them.

To help hypo-sensitive kids: Intentionally providing them with something in hand to focus on really helps them feel calmer and participate.

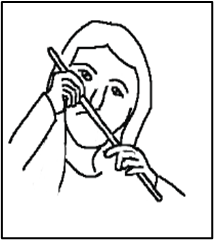

Hyper-sensitive: This child is over-sensitive to what they are seeing and will often look off into space in order to protect themself from the barrage of information that they are feeling. They may well still be listening, but just not looking.

To help hyper-sensitive kids: Supporting them by understanding that visual input may be overwhelming and giving them alternative visual options like lyric sheets and music pages.

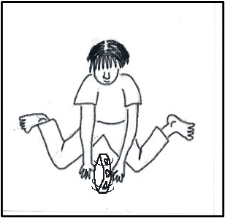

Proprioceptive Sensitivity

The proprioceptive system is located both in the cerebellum and in our joints and ligaments. It helps us understand how the parts of our body are working together, where our limbs are, where our body is relative to the space we are in, and where we are in relation to other people in that space.

Hypo-sensitive: Children with hypo-sensitive proprioceptive systems are generally sensory-seeking: they need hard input to help them know where their bodies are in space. These are the kids who are likely to be tossing their dance partners on the floor because they don’t know how to move gently. They love high-impact activities and really struggle to sit “still.”

To help hypo-sensitive kids: Providing them with excuses to move and carry heavy items really helps them stay calm.

Hyper-sensitive: Children with hyper-sensitive proprioceptive systems are generally sensory-avoiding: they are uncomfortable with playgrounds and crowded spaces, they don’t like movement games or sports, and they are often afraid of the chaos of a classroom. This can affect their mood and their demeanor.

To help hyper-sensitive kids: Support them by understanding their need for more controlled spaces and giving them the possibility of participating from a space away from the crowd.

Vestibular Sensitivity

The vestibular system is located in the inner ear and helps control one’s sense of balance, as well as our orientation in space. This system helps with eye-hand and eye-head coordination and, therefore, is very important for academic success. It also significantly impacts emotional regulation.

Hypo-sensitive: Like children with hyper-active proprioceptive systems, children with hypo-sensitive vestibular systems need to move a lot. They also will likely struggle to sit “still” and can focus and learn better if they are allowed to move around and fidget. They like to rock, squirm, jiggle their bodies, shake their legs, tap their foot.

To help hypo-sensitive kids: Provide movement breaks, movement space, jumping time, high-impact time.

Hyper-sensitive: Similar to children with hyper-sensitive proprioceptive systems, these children also often avoid movement and crowded spaces. They do not like spinning or swinging or dancing: they are extremely uncomfortable having their feet off the ground. They are often prone to carsickness, so may arrive at school feeling queasy.

To help hyper-sensitive kids: The opposite: provide rest breaks, rest space, no-movement time.

Interoceptive Sensitivity

The interoceptive system provides us information from our internal organs, such as body temperature, hunger, pain, fatigue, heart rate, breathing, feeling sick, and the need to go to the bathroom.

Hypo-sensitive: These children truly may not be getting information from their internal organs, which means that they may not know that they are hungry, tired, angry, loud, etc.

To help hypo-sensitive kids: Helping them identify internal feelings and sensations is very important. They rarely can do it on their own.

Hyper-sensitive: These children may be so affected by internal sensations that they have trouble focusing on anything else. They are often highly anxious.

To help hyper-sensitive kids: Supporting them by understanding their anxiety and not belittling them helps them calm down.

As musicians working with children in a variety of settings, we always want to know how we can use our music to help. For those of us who write, we are eager to write the songs that will reach children and help children heal and have the freedom to be a kid having fun.

To that end, in addition to making sure that the content, intent, and lyrics of the material we share with our students is musical, educational, and inclusive of all, we also need to make sure that our programs are sensory friendly. People often ask me for songs for a sensory-friendly program, and the truth is that there is no way to construct a prescribed list because every single situation is different. But in a performance space, our interactions with the kids who are out of sync with the rest of the crowd will go a long way to shape their experience and provide a message of inclusion.

If we do not expect everyone to conform to our instructions and give space for different ways of interacting with the music, we are giving the message that difference is beautiful! To address all the myriad sensory needs that are present at any moment in any space full of humans, we can intentionally vary the tempo and volume of our musical selections. We can play that loud, fast piece knowing it will help kids with hypo-sensitive systems, but make sure to follow it up with a slower, gentler piece to reach the children with hyper-sensitive systems. Many of us do this intuitively anyway, but I hope this article provides more guidance for putting together that set list.

Please reach out to me if you have questions or thoughts: joaniecalem@gmail.com.

Works Cited

Miller, L. J., S. A. Schoen, S. Mulligan, and J. Sullivan. 2017. “Identification of sensory processing and integration symptom clusters: A preliminary study.” Occupational Therapy International, 2017, 2876080. doi.org/10.1155/2017/2876080

Swedo, E. A., M. V. Aslam, L. L. Dahlberg, P. H. Niolon, A. S. Guinn, T. R. Simon, and J. A. Mercy. 2023. “Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences among U.S. adults — behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2011–2020.” MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72(26), 707–715. doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7226a2