(photo by Irene Young)

(photo by Irene Young)

An Interview with Frankie and Doug Quimby

The Georgia Sea Island Singers

by Phil Hoose

James Brown, long billed as “The Hardest Working Man in Show Business,” has nothing on Frankie and Doug Quimby.

The Quimbys, who are better known as the Georgia Sea Island Singers, work more than 300 days a year, usually performing four to six shows a day, and have been doing so for twenty-five years. Through games, songs, and rhymes such as “Shoo, Turkey,” “Hambone,” and “Pay Me My Money Down”—all of which originated with slaves on the islands off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina over 200 years ago—they preserve a lively record of the deepest roots of African-American heritage.

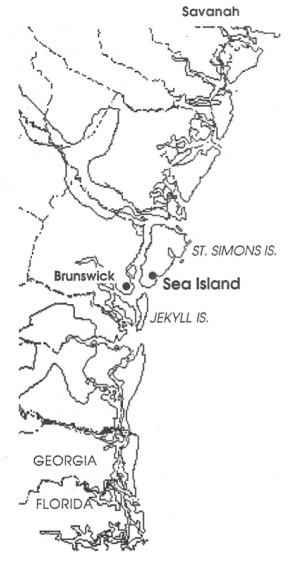

The Georgia Sea Island Singers first performed in the 1920s for tourists at local hotels on St. Simons Island, one of ten small islands off the Georgia coast. There have been more than a dozen singers in the group at some times, just two or three at others. They were recorded by folklorist Alan Lomax in 1953 and toured the nation for the next two decades under the charismatic leadership of Bessie Jones.

In those years they often performed in aprons and bandannas, which sometimes embarrassed the younger members of the group. Jones ignored the criticism. “I wear them because my grandma wore them and my great-grandma wore them,” she said. “I’m proud of them and proud of the way they wanted to be. And this is the way they dressed up when they wanted to go out, and I think they looked beautiful.”

End of discussion.

The Sands of Time

The ten sea islands of Georgia are among scores of barrier islands extending from Florida to New Jersey which were formed when currents carrying sand, usually from north to south along the Atlantic Coast, ran into bays turning inward or points of land jutting outward. The flow had to slow down to turn a corner, and the sand dropped to the ocean floor.

Over millennia, the sand deposits built into ever-shifting islands, constantly changing in shape, and separated from the mainland by varying distances. According to Doug Quimby, the water is still so clear around several of the Georgia islands that “You can see the crabs going right into your basket and you can watch the fish bite your hook.”

Because the Islands were not linked by bridge to the Georgia mainland during the period of slavery, songs and games that had originated in Africa—as well as the oral history of slavery as told by slaves themselves—were isolated and preserved on the Islands with relatively little contamination from mainland culture. So too was their African-based dialect called “Gullah,” still spoken there.

Quimby History

Frankie Quimby, 57, is the oldest of thirteen children. She grew up in a sea island family that traces its lineage back to the Foulahs—a tribe from what is now Nigeria—who were captured and enslaved on plantations along the Georgia coast. Exposed to slave lore from girlhood, she grew up respecting her forebears’ “mother wit” and capacity to endure hardship.

Frankie met Doug Quimby, 58, a sharecropper’s son from Bacontown, Georgia, while he was performing with a gospel quartet on St. Simons Island in 1968. They were married three years later.

They began performing with Bessie Jones in 1969 and took over as the Sea Island Singers when Jones could no longer perform. Their passion is to pass on the story of their slave heritage as a source of pride.

“Our ancestors survived by being strong, creative, and intelligent people,” Frankie says. “I think the children of this generation need to know that.”

The Quimbys Today

The Quimbys live in Brunswick, Georgia, near six of their ten children, most of their thirty-eight grandchildren, and an ever-growing number of great-grandchildren. Doug Quimby is a soft-spoken man who looks a little like Dr. J with salt-and-pepper hair, a long face, and a neat mustache.

Frankie Quimby, animated and intense in conversation, tends to lean forward to tell her story while Doug sits back. Her voice is often filled with passion and conviction. Laughter frequently bubbles to the surface.

This interview took place in the Quimbys’ room in the Tewksbury, Massachusetts Holiday Inn, an hour after the last of their four school performances for the day. Frankie’s stomach growled throughout, but she refused to quit talking about children and history for something as trivial as dinner. (“My stomach’s just noisy anyway… I could be just through eatin’ and it’d be noisy.”)

This was a wonderfully musical conversation, during which Frankie and Doug taught several songs, and Doug sang seven different versions of “Amazing Grace.” In some ways, it was their fifth set of the day.

Our Talk with Doug and Frankie

Where all have you been this week?

DQ: Well, let’s see. We were up here in New Hampshire Thursday and did three concerts. Then we went home. We drove all night and got home Saturday about 7:00 am. We did a concert on Keawah Island South Carolina Saturday night, and started back up here Sunday morning about 5:00 am. We drove straight through to Boston and got there about 10:00 pm Sunday night.

We had four shows Monday—two elementary schools in Londonderry, New Hampshire, then a K-8 in Manchester.

Amazing… How many shows do you figure you do in a year?

FQ: Oh, I don’t know. Sometimes we do six in a day, like two in the morning, two in the evening, a Boy Scout or Girl Scout at five, and a PTA at seven. You count in festivals, family gatherings, teacher workshops, churches, then schools when in sessions...it must be over a thousand shows a year.

Are you wearing down at all?

FQ: The older you get, the more you know the miles are ticking by. The legs get tired now, the back. We used to be able to just shoot from here to there.

DQ: There’s wear and tear everywhere. Like today, after our first concert in Londonderry, I was really tired. But when I got to Manchester and looked into their faces, I was full of energy. I was ready to do some more. They start waving at you, and you wave back, and they’re smiling and you’re just ready to go. You have to love children to travel this much.

Remembering Bessie Jones

Can you still remember your first show?

FQ: Oh yes. We started out with Bessie Jones in 1969. My first husband was her son. After we were divorced, and me and Doug got together, she knew that Doug could sing. She’d heard him sing in quartets in church. We would fill in for her, because she was always double-booking.

If you called Bessie up and asked her to sing, she’d say, “Yes, send me a ticket.” Then if someone else would call for the same day, she say, “Yes, send me a ticket.” First ticket to get there, that’s who she’d sing for.

Finally I started booking for her. And this double booking was happening all the time. So one day she said, “How ’bout you and Doug and the children going to one and I’ll go to the other?”

First time, we caught a bus to Towson, Maryland to sing with Mike Seeger and Bukka White and Hazel Dickens, and Bessie caught another bus to Tennessee to sing with Guy Carawan. That’s how we started (laughs).

I’ve heard so much about Bessie Jones. What was she like?

FQ: She loved people, and especially children. Anybody’s children. Before Alan Lomax got her on the road, she would take people’s children and raise them. She would take your babies and just keep them if you needed her to. I had never met anybody like her. And that woman could sing! Powerful! She could sing for four hours straight in the sun and it wouldn’t bother her.

Just before she stopped traveling, though, her singing voice got really weak. You could hardly understand her. We had to explain the games because the children couldn’t understand her. God, she couldn’t deal with it. It just frustrated her so. Her mind was still able but her body was decaying. Singing had been her life. She still needed to do it but it was going away. She couldn’t deal with it. She felt useless. She would say “I got to do this! I got to share this! I got to keep goin’!” And her body would say, “Nope.”

The Beginnings

How did the Georgia Sea Island Singers get started?

FQ: About a hundred years ago this group started out with just the people on the Island singing for tourists. There was a white woman, Miss Lydia Parrish, who wrote Songs of the Sea Islands. She would let the black people come to her house and sing for tourists. Finally she bought an old slave cabin, and tourists could come down and hear slave songs sung where they had been sung. Then after a while the hotels caught on and saw it was good business.

How did Bessie Jones get involved?

FQ: Bessie wasn’t from the Island, but she started going there in 1919. Finally the people who lived there asked her to sing with them because they’d heard her singing in church. It was quite an honor, since islanders do not ask outsiders to sing with them. She must have been singing up a storm!

Then Alan Lomax went to St. Simons in 1953 to interview people and record singers and he singled out Bessie. One reason was that she would talk to him and tell him about the songs and games and history, which she had learned from her grandfather and the island people. The others wouldn’t talk. They still clam up.

And they would still try to run away. And the slave owners couldn’t understand it. ‘Why?’ they would say. ‘We’re being so good to them.’

Bessie finally got the others to travel with her. Up to then they had been called “The Coastal Singers.” There were about fifty of them, from all the surrounding islands. From Camden County and Mackintosh and Liberty Counties. And Miss Bessie could not master the Island culture, so finally she sent for them.

And when they came, it became “Bessie Jones and the Georgia Sea Island Singers.”

Then in later years they stopped going and Miss Bessie asked me and Doug to go. That’s how she got us going, in 1969.

Roots

Are you able to trace your own ancestry back to Africa?

FQ: I can. My people were from the town of Kianah in the District of Temourah in the Kingdom of Massina, which was on the Niger River. When we needed some biography on me, we went to the Hopeton-Altama Plantation, where my people were slaves. They brought them from Africa to the Islands and unloaded them.

Some were taken to Brunswick, to the plantation, eight miles across the bridge to the mainland. Some were taken south to Camden County and some were taken north to Mackintosh County. They brought some to Brunswick, to Hopeton-Altama Plantation. They were slaves there. We went to those records and found a list of slaves. We found one of my ancestors; her name was Frankey. They wouldn’t let her use her African name, so they spelled her name F-R-A-N-K-E-Y. By the time it got to me in the 1930s, it was FRANKIE. We’ve got a relative that’s a hundred years old today whose name is Frankey. It was my great-great-great grandfather that was brought to Hopeton-Altama.

These are rice plantations, not cotton, right?

FQ: Yes, and that was very important. You see, cotton was king on those plantations at first. But they found that the slaves that were taken from the coast of Sierra Leone knew how to grow rice. So they converted the plantations to rice to make more money.

But you grow rice in water and muck. That breeds mosquitoes, and mosquitoes caused malaria.

Most slaves were immune to malaria because of the sickle cell, but the white plantation owners were not. The slaves were giving malaria to the owners, so the owners would leave the plantations along the sea islands to black overseers for nine months of the year, during the growing season. After the Civil War ended they gave the land to the blacks, because whites couldn’t live there. It wasn’t like the mainland, where sharecropping set in.

So if a cure for malaria had not been found, the Georgia Sea Islands would still be inhabited mostly by blacks even today?

FQ: Probably.

Was slavery less harsh there than in the uplands because the whites were gone?

FQ: Yes. The history and culture of slavery survive better there than anywhere else because the owners were usually gone and those people could keep up their African ways. They could eat good and practice their native language. Who was gonna tell when the owner came back? They could grow food, and even when the slave owners were there they could catch things out of the water at night.

DQ: And it is known that Glenn County was the only place in all the South where a slave was not allowed to be whipped. They could be punished severely, but not whipped.

FQ: The older people told us that. And they said there was a preacher who would go around from plantation to plantation and ask the slaves, “Are you being treated all right?” And some slaves were allowed to visit their friends and relatives on other plantations.

But they still weren’t free...

FQ: That’s right. And they would still try to run away. And the slave owners couldn’t understand it. “Why?” they would say. “We’re being so good to them.” But nobody wants to be owned by anyone. Nobody wanted to be a slave.

Doug, can you also trace your heritage back to Africa?

DQ: No, I wasn’t born on the coast like Frankie; I grew up upland around Albany, Georgia. When I was coming up a lot of the old people didn’t say much. They didn’t know it was valuable. I didn’t understand until after my granddaddy died that he was from South Carolina and that he spoke Gullah. We all just said, “Pa talk funny.” We didn’t ask why.

We didn’t ask why. He’d say, “The sun is shayning,” and “Geed up bo” for “Get up boy.” Now I know he was speaking Gullah. Then later when I came to the coast and I heard a lot of it, everyone talked that way. Granddaddy died before I could ask him about it. But he was a Geechee (laughs).

Starting Young

Did you sing professionally before you joined the Sea Island Singers?

DQ: (Laughs.) My first paying job came when I was four. I grew up on a plantation out in the country. The overseer’s mother, a white lady, heard me singing and fell in love with the sound of my voice. Every Saturday we would drive into town in the overseer’s truck to shop. The glass between the cabin and the truck bed was broken out, so you could hear through. She wanted me to stand in the back of the truck and sing to her though the broken glass all the way into town. I sang a song about “My Mother’s Dead and Gone,” and she would cry all the way into town.

When we got to town she’d wipe my eyes and give me a quarter. That quarter was big money. I could go into the store and get a drink and some crackers for a dime. There was still money left over, and during the week I’d spend the rest when the rolling store came—that was a truck with a little house built over the back. It would carry meat and rice and perishable goods and also candy. I would come by on the plantation and I’d spend the rest.

How’d it make you feel to be able to make this woman cry?

DQ: I didn’t know for sure why she was crying. Then later I realized maybe her mother really was dead and gone. She loved her mother; I guess the song really brought it out. We’d come back to the country in the evening when it cooled down and she’d have me sing it all the way back. And she would cry all the way back, too. And during the week when she wanted a good cry she’d send her grandson to our house to come get me and I’d sing it to her then. After a while she’d rise up from her chair and say, “That’s enough,” and she’d give me wheat bread and syrup. That’s the truth. That was my first paying singing job (laughter).

The Singing Style

Doug’s voice is just amazing to me. So rich and powerful. Most people’s voices would have given out long before the fourth show.

FQ: I know what you’re saying. I always think, I know Doug’s people came over on that boat because Doug can sing so far. Like when they took the drums away they would sing on one plantation and you could hear it on another. And Doug could stand here and open his mouth and sing and you could hear him a long ways away. He overpowers microphones sometimes. He has to move it out of the way in small rooms because he would blow ’em out of there if he used it (laughter).

DQ: Well, years ago when I started singing with gospel quartets we didn’t have microphones. You had to really put out. Then, following a mule out in a field, singing out in the open all the time, I developed my lungs. I very seldom get hoarse. Once every three or four years.

Did you want a career in gospel music?

DQ: When I was real young I used to imagine myself singing in a little quartet like the Soul Stirrers or the Blind Boys of Mississippi. And I used to have a vision a long time ago. I would be back in the field where I worked, near the woods, almost to a fishing hole where we’d fish if it rained. I would be plowing, and I could imagine myself singing to thousands and thousands of people in an open clearing.

And you know, it actually happened. Frankie and I went to Eureka Springs, Arkansas for a festival. And we were on a big huge stage right like at the bottom of a mountain. And I could see people just as far up that mountain as my eye could see and as far to either side. And all behind me. The vision had happened.

Delivering Important Messages

You have preached a positive message for so long now, telling young African-Americans especially to be proud of their heritage and of the resilience of their ancestors during slavery. But I wonder if the horror of slavery ever sweeps over you personally?

FQ: With me it doesn’t that much, because I’ve never had to endure hardship. But Doug has. Doug grew up sharecropping in Southwestern Georgia. Eight people grew up together and made $9.25 for a whole year. Doug knew about getting up early in the morning to plow. He knew what it was like to be treated bad before Dr. King came and after Dr. King came. But I was born and raised on the Georgia Sea Islands. I had it better. The ocean gave us food and the old ways had survived. That helped. I don’t know what it is to be hungry, or to work and not get paid.

DQ: Sometimes I think about it but I don’t let it get me down. Once a guy took all the money I had made in a whole year. I got to thinking about how hard I had worked for that money. I had worked in the fields all day long in that hot sun. Then at night the dew would start falling and I’d have to hook the plow up to the duster and dust the cotton fields with poison to kill the boll weevils, especially on nights when the moon was shining. I’d work till eleven or twelve at night. Then I’d go get some sleep till four or five and dust some more till the sun came up and made the leaves too dry for the poison to stick to them. I would let it get me down until Christ came into my life.

Do it right. Don’t change it. If you change it, it takes away from why the ancestors made up the games and songs.

Another thing that helped me through was that I saw that whites were treated bad too. Poor whites that were sharecropping. I’m not talking about what I heard someone else say. This is experience that I seen for myself. They worked hard like we did. I used to play with white children and work with them and sing with them and my mother and the mother of one boy I worked with cooked together and we would eat together. At twelve o’clock we’d leave the fields and everybody went home and ate. It was like a big family.

Respecting Tradition

How important is it to you that the games and songs that developed during slavery be performed faithfully, with historical accuracy?

FQ: I want performers and music teachers to do it right. Don’t change it. If you change it, it takes away from why the ancestors made up the games and songs. Try to find out why, and the real way to do it. Don’t add something on because you can’t do it like that. If you’re going to teach it or record it or put it in a book, try to find out the real way that they did it. I’ve heard people say, “Oh well, in folk music it don’t matter if you change it....” That’s not true! It does matter.

DQ: That’s right. When we do things we do it exactly the way we were taught that slaves did it. Once we were out in California and we saw a teacher having the children doing “Draw Me a Bucket of Water” sitting down. How you gonna jump around in a ring sayin’ “Frog in the bucket and you can’t get him out” when you’re sitting down?

FQ: They did that song when they were entertaining slave owners on a Sunday evening. They had to put a lot of action and a lot of rhythm into it. Sometimes we’ll go in behind someone else who has taught them differently, and the kids’ll say, “Well, I thought there was something wrong...it didn’t make sense that way.”

The “Comfortable” Dance

I understand you know how the Charleston got started.

DQ: The Charleston was originated from a slave dance called “Jump for Joy.” You see, the slaves were not allowed to cross their legs unless they were performing a game or dance for the overseers. Because crossing your legs meant you were comfortable. Slaves were supposed to be submissive at all times. So they invented a dance that gave them a chance to cross their legs in front of the master and the overseer.

It was beautiful, so they called it “Jump for Joy.” Years later, as things began to change, someone saw the same dance down in Charleston, South Carolina. Little finger pop, little body twist, and they renamed it “The Charleston.”

When did you first hear that story?

FQ: That was an old story. It was said before it was published. Same with the song “All of God’s Children Got Shoes.” They were saying, “I got shoes, You got shoes, all of God’s children got shoes. When I get to heaven, gonna put on my shoes and gonna walk all over God’s heaven.”

They didn’t have shoes. But they were saying, when I get to heaven I’m gonna have a pair of shoes. They’d be entertaining the slave owners on Sunday, dancing as they were singing. And they’d get in front of the owners and sing, “Everybody talkin’ ’bout heaven ain’t goin’ there,” and they would kind of point over their shoulders at the owners. The owners didn’t know they were talking about them.

Singing for the World

Have you ever had a chance to sing in Africa, for African children?

FQ: We did a concert at Freetown University in Sierra Leone. The children were receptive, but I had thought they would know the songs and games that our ancestors did when they got to America. It turned out those songs and games were made up after our people got to America, to express how they felt and to talk to slaveowners through songs and games.

The children didn’t know our songs and games, but they did recognize some rhythms we were doing. For example, there was something in a lot of songs and games that we learned to call “Shout.” But when we performed it in Africa, they said, “Oh, you do Gumby.” That’s what they called it.

And another thing was the slaves on the Georgia Sea Islands processed rice by hand. They didn’t have machinery. And we still do it for tourists, pound the rice by hand. We demonstrated that in Sierra Leone in ’89 for the United Nations. And they said, “How do these Americans know how to beat rice?” They still do it by hand there. They were shocked. In America, the slaves just left it on record for us as “The Rice Dance.” And when we got to Sierra Leone, they told us the name of it.

History Can Build Pride

As you present slave material to children in the United States, do you find that some African-American children are embarrassed to be reminded of their heritage as slaves?

FQ: It’s getting better. There are still places where there’s embarrassment. But because of performers going in, because of PTAs and PTOs trying to make them aware of all the different cultures, now they seem to be more aware. There are still some children that will hold their heads down until they get into the program and they see that their peers are enjoying it. Then they get to enjoy it. A lot of it is because of the effort that performers and sponsors make.

Have children changed much in twenty-five years?

DQ: Some children, especially in the city schools, can get a little rough now. They can be noisy, and play while you’re performing. You gotta constantly tell them, “Boys and girls, be quiet.” This doesn’t happen outside the cities.

FQ: Children are children no matter where you go, but you have to use different techniques now. Now, you have to say, “We’ve represented the United States in Lillehammer, and in Africa… We were on Nickelodeon Television. You have to impress them before you start, so they don’t think you’re so dumb. You have to do this to get their attention sometimes. Years ago you didn’t have to do this.

The Next Generation

Are you going to try to keep the Georgia Sea Island Singers going when you’re done?

FQ: Yes, we are training the children and grandchildren now. Our children are all grown now. They had traveled with Bessie Jones when they were young. For years we had been beggin’ them, “Start back.” Finally we said, “Look, we’re getting older. We can’t do this forever. You need to come back and learn over again, and take up where you left off.”

Finally, two years ago, a light went off in two of them’s heads. One day they said, “When you all gonna train us? You said you were.” I said to Doug, “Doug, are these the same ones we been beggin’ for years?” Now they’re ready to go.

They went to Wolf Trap with us last month and to Chattanooga at the National Storytelling Festival. They go. Now they can’t go enough. Something happened in their minds, they saw that it was all gonna be lost if they didn’t go.

Do the grandchildren go too?

FQ: They go from the time they’re two years old to the time they’re thirteen. Then they start liking boys. Or they get in middle school and they get shy; they don’t want their peers to see them doing something. They find excuses. Then after they’re fifteen they’re ready to go back again. We use them to demonstrate games like “Shoo Turkey.”

Did you ever try to train children as apprentices that were outside of your family?

FQ: Oh yes, we try to train all children. In middle schools, at the end of a concert, when there is question and answer, I ask them to tell me, would you like to do this for a living?

Most of the time they say yes. They want to know how much money they could make.

Did any child ever keep at it, and pester you to let them go along with you?

FQ: They have asked us to go with us, but we’re on the road so much that you can’t carry them. But I’ll tell you, it’s beginning to bother me again, and I wonder, “What child out of all our children, and what child in the next generation, is going to do what we did?” It takes dedication.

DQ: It takes love.

A Loving Motivation

Why is the love in you?

FQ: (leaning forward) God, we just love it! This is where we come from. We are the generation that had to make it survive and we don’t want to see it die. If it dies we’re in trouble. I’m a firm believer that you don’t know where you’re going until you realize where you’ve come from. Then you can appreciate your education and where you’re trying to go in life. This is us.

Even when we’re with children, it makes them proud when we say, “MC Hammer didn’t create rap. Our ancestors were rapping on those plantations about what was happening in their generation. It’s just that today’s rapping has taken up and blown it out of proportion, saying wrong words and stuff.” It seems to make our children proud when you say the slaves were rapping. They’re not ashamed.

When we do hambone, and we say that the slaves created hambone because their drums were taken away and they used their bodies to make music…the kids just listen. It sends a bell. It makes them proud. It gives them a sense of who they are and where they come from. It’s important for us to keep going.

What do you want white children to learn from your concerts?

FQ: I feel like we should be aware of each other’s culture and heritage. White people should be aware of our heritage and culture. Then they could understand us better. Same with us and you.

We’re thrilled that you’re going to be with us at our CMN gathering. I know you’ll talk much more then, but I wonder, for now do you have any advice for those of us who are just beginning to use music to work with children?

FQ: Over the years we’ve learned some tricks. Take hambone. At first they were shy and we’d keep tellin’ them to do it. Now we tell the kids not to do it. To put their hands on their laps and keep ’em there because that way they’ll be sure not to do it. To lock them together and keep them locked and put them on their lap ’cause that way they’ll be double sure.

Just watch and listen. Their little hands’ll be clutched together and they’ll still be tryin’ to do it. They can’t stand it. And after the concert we’ll see ’em in the hall, poppin’ their mouths and tryin’ it.

DQ: I think it’s most important to really like children. I just like working with children. Even when I was coming up as a teenager I had a cousin that had a baby and I would walk two or three miles over to her house just to hold that baby.

It just gives me such a thrill to look into their smiling faces. Children generate energy in me.

FQ: Bessie used to say this same thing years ago when we started. We were in our twenties, and we didn’t know what she was talking about. But now we do.

Children are so important. They can wear you out, but they give you back more.

Children can wake up something in you that’s been dead a long time.

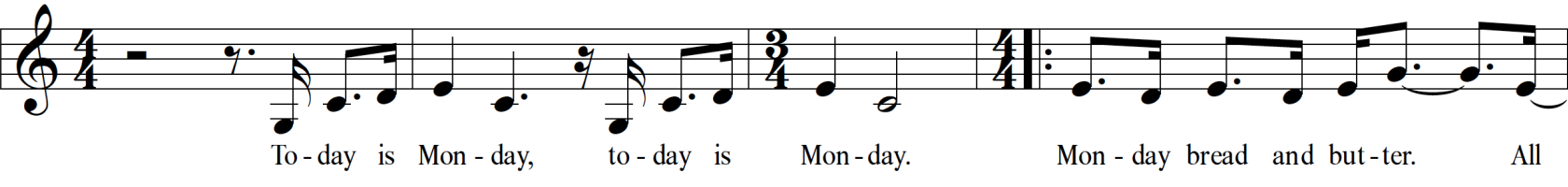

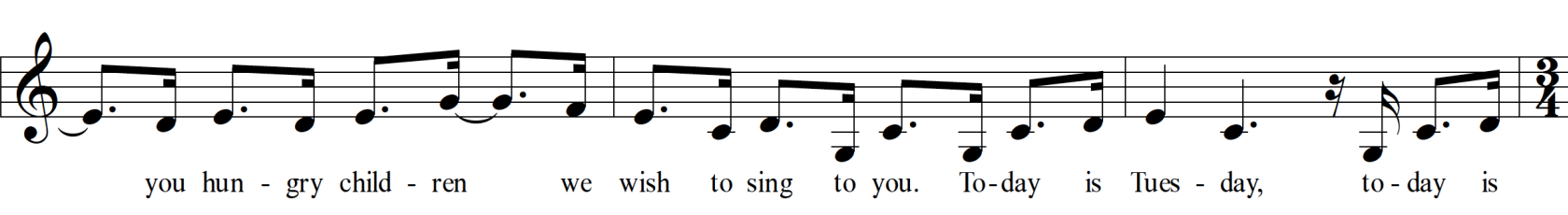

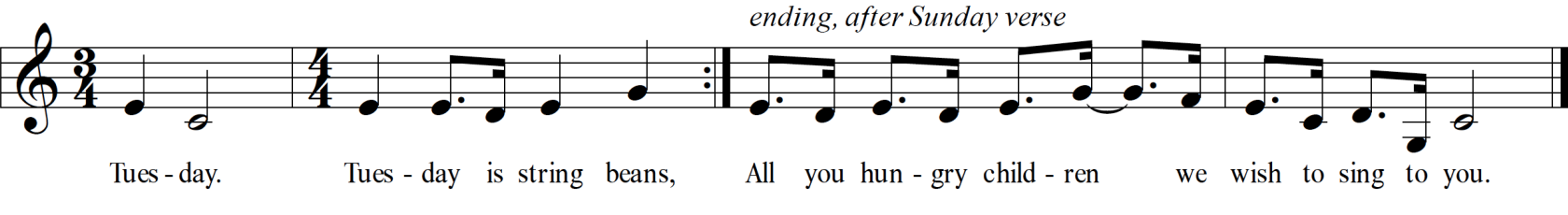

We Wish to Sing to You

traditional song from Georgia Sea Islands

Frankie and Doug Quimby (The Georgia Sea Island Singers) often use this song as an introductory piece for their concerts. Many songs from the islands are used to teach children facts: counting, the alphabet, times tables, etc. Most, as in this song about the days of the week, teach the numbers or words both forward and backward!

Today is Wednesday, today is Wednesday.

Wednesday is soup —, Tuesday is string beans,

Monday bread and butter.

All you hungry children we wish to sing to you.

Today is Thursday, today is Thursday.

Thursday is roast beef, Wednesday is soup —,

Tuesday is string beans, Monday bread and butter.

All you hungry children we wish to sing to you.

Today is Friday, today is Friday.

Friday is fish —, (etc.)

Saturday is pay day

Sunday is church day

(Each verse adds another day, then sings backward through the days of all the previous verses.)

Further Resources on the Quimbys and Gullah Traditions

http://www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/vtl07.la.ws.style.quimby/frankie-quimby-of-sapelo-island

http://today.uconn.edu/2014/10/singers-keep-gullah-traditions-alive

http://www.gacoast.com/navigator/quimbys.html

Originally published in Issue #21, Fall 1995.