Healing From the Past, Creating the Future

An Interview With Dr. Tawnya Pettiford-Wates

by Ginger Lazarus

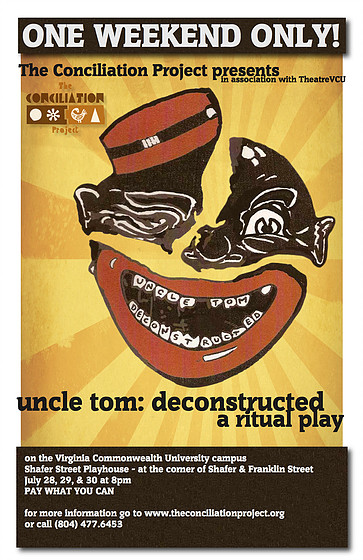

As a teacher, theater artist, PIO! editor, and seeker of deep discussion on social justice issues, I got pretty excited when I learned that Dr. Tawnya Pettiford-Wates was to be the keynote speaker for the 2018 CMN Conference. Dr. T, as she is known to her students, is a playwright, director, actor, poet, writer, and teacher. Currently a member of the theater faculty of Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, her rich history of artistic achievement spans acting roles on stage, screen, and television; featured voice talent in a video game; and director of many highly regarded productions. In 2001, she founded the Conciliation Project (TCP), a theater company with the bold mission of creating works that directly confront stories of racial injustice and oppression in United States history and present. Opening up painful and difficult conversations that shake audiences to their core is all part of a day’s work for Dr. T.

I could not wait to learn more about Tawnya’s experiences and gather some background for the topics she will broach in her keynote this October. She graciously sat down with me (via Facetime) and shared her spirited wisdom.

Ginger: How did you come to do this work of dismantling racism through art?

Tawnya: It was not intentional, let me just say. It’s very difficult work. It’s like, I take medicine, but I don’t really want to, but I recognize that I need to, so I make myself do it.

We lived in Seattle, Washington, for twenty-three years. I was the head of theater at what was then Seattle Central Community College, now Seattle Central College. I had a lot of leeway, and Seattle was one those places where they were really into collaborative learning, interdisciplinary work. So, I had an opportunity in a class to look at the archetype of uncle tom.

How did you think of looking at uncle tom, specifically?

When I was doing my dissertation a decade before that, I looked at uncle tom and tokenism within the arts community. Basically, it was coming back to something that I was curious about. I had no agenda, no idea about what it was going to be.

Do you mean “tokenism” as in a very limited representation of African Americans?

Yes! Like for example, communities of color don’t normally use the word “diversity.” And if we do, it’s in a different way than in the dominant culture: that idea that when you have one person who is different, then all of a sudden you have diversity. And that idea of the burden of tokenism, you know, of being made the “authority.” No group of people is monolithic! There’s diversity within groups of people!

So, the class was announced, and I gathered the people who wanted to participate. It was a coordinated study, which meant we were using history, sociology, theater, and English, so people from all those disciplines could be involved. In this generation, a lot of people know the moniker of uncle tom but don’t necessarily know where it came from or what it’s attached to. So to begin with, we had to read Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which some students vaguely remembered from secondary school English, but we delved into it with the language we have now and the understanding of our history as a country. And they recognized that the novel was problematic, in that Harriet Beecher Stowe was setting up an argument for and against slavery by contextualizing it in the frame of “the good master” and “the bad master” and “the good slave” and “the bad slave.” She was an abolitionist and all that, but just the idea of saying “good slave” or “good master” was problematic. So, we began with that as our discussion, and we decided we were going to deconstruct uncle tom.

I have a particular method I use in devising theater, and we went about implementing that, when all of a sudden, a student raised his hand and said, “Dr. T, how are we going to do a play about deconstructing uncle tom when there’s no black people in the class?”

And it was true. We had people from other groups—Asian, Latina, gay, lesbian—but we didn’t have any African Americans. I had not even really looked at that as an issue, and so I said—it came to me from my muse—“We’re going to do a minstrel show.”

And of course, all their faces were horrified, and they went, “What do you mean?”

And I said, “Only, we’re going to caricature white people and white culture in the same way black people and black culture is caricatured. So, we will have a black minstrel and a white minstrel.”

Black people did not create minstrelsy. It was created by the white culture; you had white people donning black face and imitating black people as if they knew black culture. Later on, you had black people putting on black face to be a part of the theater tradition. So race, racism, white privilege, and white supremacy were at the center of every discussion we had.

We took away gender and sexual orientation—you were either a black minstrel or a white minstrel. When they first came in the room in costume and make-up, I could not tell who they were. I had worked with these people intimately for an entire quarter and I couldn’t identify them. It was perfect, but it was horrifying too. It was painful—I think I started weeping, actually.

The play, uncle tom de-constructed, was a huge success, and at the end of the play we unmasked, right in front of the audience, as a part of the epilogue. We used some language from Peggy Macintosh’s article “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack”—people carry it around without even recognizing that they have it—as we were taking off their makeup. And the audience visibly and audibly responded when they recognized that there were no black people. They saw people of color taking off white makeup, and saw white people taking off black makeup. It was like—(gasp). As a person who had worked on diversity issues for a very long time, I had never witnessed or been a part of such an honest, open, transparent dialogue about race, racism, systems of oppression, and privilege as in that first dialogue. People in the audience were weeping, and we had to hand out tissues, which later became a part of our practice. You’ll see at the conference!

You’ll bring a huge box of tissues?

Yes. And we began to ask the audience to also wipe off their masks. Particularly we were talking about race and historic oppression and the trauma that creates in all people—all people, whether you are in the dominant culture, or in the culture that is historically oppressed—it creates dysfunction, disharmony, disunity amongst all people. And people were weeping, they were talking to us, they were talking to each other—it just started pouring out of them—and we recognized that we as a culture were in serious need of healing, that we all had been affected traumatically by racism, by white supremacy, by historic oppression.

We were talking about race and historic oppression and the trauma that creates on all people. …And people were weeping, they were talking to us, they were talking to each other—it just started pouring out of them—and we recognized that we as a culture were in serious need of healing.

I’m really struck by how this physical experience of the mask was able to tap into that so deeply.

I stood there in awe, literally, because I had never seen people talk so honestly and authentically about these issues—people of all colors and of all classes, a very eclectic audience. So, we recognized that we had something here and we needed to find a way to use it as a tool, because clearly it had therapeutic value.

That is how the Conciliation Project came out of a community effort to keep the original idea alive. We decided that we were going to be called the Conciliation Project, not the Reconciliation Project, because you can’t redo something that you’ve never done before. The process is hard. It’s hard. You have to be intentional about it. And it takes time! Kind of like in AA—once they admit and embrace the fact that they are alcoholics, they begin the practice of reconciling all the broken relationships they created. And truth-telling becomes a very important part of that, no matter how painful that truth is. In this work of undoing racism and repairing its damage, we recognize that, unlike in theater where you get instant gratification—the show’s great, people applaud, it’s over and you move on to the next thing—this was going to have to be ongoing: this was about a practice, and the practice involved a process, and that process went way into the future.

How has the process developed since 2001? At this point, how do you find ideas for new projects and develop them?

We decided the mission of the Conciliation Project is to promote, through active and challenging dramatic work, open and honest dialogue about race, racism, and systems of oppression in America in order to heal its damaging legacy. The idea overall is about healing from the trauma that these systems have caused historically. The next piece that we did was called Genocide Trail: a genocide un-spoken. A lot of people believe that Native Americans are no longer around, because they don’t see what they saw in John Wayne Westerns—they don’t see teepees, they don’t see feathers. Or they believe that Native Americans only live on reservations. We recognized that we had to start with the story of how America came to be. And in the Pacific Northwest, we had Native culture all around us that we could bring in to help us create this new piece. We had a multiplicity of tribal elders; we had a person from the tribes up in British Columbia who was now living in Seattle. They were our native consultants and connected us to various tribes in the region. We did a lot of work on reservations close to Seattle and we invited them to be a part of that process. So, that was the next piece that we did, and it was just as devastating because we continued to use the idea of minstrelsy. Native people are also minstrelized—I think it’s just this year that the Cleveland Indians are going to retire their mascot, and that’s great. I wish that the Washington team would do the same.

The next piece we created was called Yellow Fever: the Internment about Executive Order 9066, which affected a lot of people in the Seattle area specifically. It created the same kind of conversation, and again, we always unmasked, and we always had a dialogue. We NEVER put these horrible images and stereotypes and caricatures of groups of people on stage without being able to talk about it, without being able to unpack it.

The next play we did was Stolen Land: border crossings—which had to do with the Latin diaspora. The next piece we went into rehearsal for was about global sexism and sex trafficking—and that’s when I got the offer to move to Richmond and take a position at Virginia Commonwealth University. Initially, I thought the company would stay in Seattle and I would just come back and work with them periodically. But the company moved to Richmond. A bunch of them just picked up and said, “Let’s go to the heart of the Confederacy.” If we’re talking about where things began—

You can’t get much more potent than Richmond.

Exactly. So, the work became about training people in this process. Most of the work is collectively authored, through a process whereby we study certain historic events, certain people in history, and attempt to get inside the psychology of what was going on at that time. We write, create skits and sketches, and that is put into the frame of minstrel storytelling. With minstrelsy, you’re using music, humor, slapstick—all of these performative techniques that engage audiences in being entertained. They’re being entertained but they’re also being edutained. By the time they’re being confronted with that history, they’re already in. They’re in the pool.

So, what’s been the reception in Richmond?

We started with uncle tom, and I think people were shocked. This is a region where they know the history, but they don’t want to talk about the history. Every day when I come to work, I come down an avenue called Monument Avenue. It literally glorifies all the heroes of the Confederacy. At nighttime if you go down there you can still see them because they’ve got floodlights. I’ve been living here since 2004 and I am not used to it yet. It still affronts me when I ride down that avenue. I have to purposely avoid looking if I don’t want to see. So in Richmond, I think they were shocked that we unabashedly and unapologetically put this out there. There was this reserve amongst older people, like, “not sure if you should really be talking about that...we just put those wounds together, why are you opening them up again?” But the young people were like, “YES. Finally! Let’s get in there; let’s do this.”

So, we didn’t have any trouble recruiting people to the company to take the work forward, and I believe it really was a catalyst in Richmond for starting conversations in other organizations as well. We started getting invitations saying, “How do we talk? How do we open up these conversations that we haven’t had, that we haven’t wanted to have, but that we recognize we need to have?”

The plays you do seem to be geared toward adults and young adults, and approach the issue in a way that wouldn’t work for younger kids. Or would it?

We’ve done several plays that we’ve devised for younger kids, usually middle school and forward. But we’ve also had elementary school educators ask us to come up with something for them as well, particularly in the way of teaching history in a more inclusive and engaging way for young people, rather than from the textbook.

So, how do you talk about history to elementary school kids?

When you’re dealing with children, you’re dealing with their parents more than with them. You’re basically confronting the trauma that their parents have. They’re traumatized by the trauma of their parents.

It would be through the entertainment forms of the times, like for example, dance. And coming at it from a way that they can understand, for example, gender: what women were allowed to do versus what men were allowed to do, or girls and boys. That’s something they can understand—because girls get that boys often think of themselves as stronger, smarter, better, faster, all of that, just because they’re boys, not for any other reason. And then we move into talking about slavery. Just be very simple so they can understand that what is unfair here is also unfair here.

Do you think the images of minstrelsy are relevant to them? Do they even recognize what that is?

When we’re talking minstrelsy, we’re talking about a mask. We’re talking about a caricature, something that’s not real. One of the things people always ask us about is why we never capitalize uncle tom. It was capitalized in Stowe’s novel, but our creation and our interrogation of that character leads us to know that he is not real. We don’t want to make him a real person by giving him a proper name. We call him uncle tom like you call this a pen. It’s a thing. It’s not a person. That kind of specificity is very hard for young, like elementary school, people to understand. I think middle school students CAN understand it, and we have talked about that with them. It would be more problematic, I think, to try to unpack minstrelsy with young kids than it would be to find another way. Like, superheroes! Those are also masked—they’re caricatures, it’s not real. Using superheroes does the same kind of thing but in a way that they can understand.

Hopefully, in working with children, no one goes out and unironically does a minstrel show—

There was a teacher in Atlanta—this is an African American teacher, actually—who did do a minstrel show in her class for Black History Month.

Wow. Without contextualizing it?

In her mind, she had contextualized it. Minstrelsy is like dynamite—unless you really know what you’re dealing with, you should not be doing it. That all came crashing down on this teacher, even though she had good intentions. The incident made its way onto the local news and then the national news; she was reprimanded, the school board got involved; it was horrible.

You have to recognize that when you’re dealing with children, you’re dealing with their parents more than with them. You’re basically confronting the trauma that their parents have. They’re traumatized by the trauma of their parents. You’re dealing with history that comes to you, kind of like a virus. It passes to the kid, and then it comes into class.

Both in the sense of children whose parents are traumatized by slavery or segregation, and children of privilege who are carrying this feeling of guilt that they don’t know what to do with?

Yes, exactly! They recognize that it’s there but they don’t know what to do with it, and if they try to share it with their parents, their parents have an adverse reaction. There were kids who didn’t say anything to their parents about the minstrel show because they knew they couldn’t talk about that in their house. So, I think we’ve got to be sensitive to that with regard to young people. They’re bringing stuff into the arena that comes from their household of origin, their family of origin. You’re teaching a lot more people when that one child is in the room.

So, in concrete terms, what is a good way to start teaching kids about privilege?

We’ve got to do both/and. We’ve got to simultaneously try to engage parents, other adults—whoever those kids are connected to. Perhaps there can be some community classes, like family classes, where they’re learning it together, rather than just the children in the classroom.

Some ignorance is willful, and some of it is because if you live in a community where people are only like you, you’re going about your life and you’re not going to really be conscious of other people’s needs, or other people’s history, or other people’s perspectives. This is just how you were raised! So, it’s not about blaming, or wanting to make someone feel guilty, it’s just about, you know, let’s turn on the light. Let’s learn things we don’t know. Let’s hear from people we’ve never heard from before.

Let’s turn on the light. Let’s learn things we don’t know. Let’s hear from people we’ve never heard from before.

Once you open up that conversation with people of any age, what do you send them off into the world with? What can they do now that the light is on?

It’s up to you. Now that you have seen, you’ve got to do something with what you’ve seen. For some people, they live in cities or other communities where people of all kinds are very readily accessible. And some people live in regions of the country where, if they want to see someone different, they’re going to have to intentionally take a journey. I tell people it’s far easier these days than it ever was before. Look at you and me: you’re in Massachusetts and I’m in Virginia and we’re looking at each other! In this world, where there’s a will there’s a way.

I am a pen pal with some people who are incarcerated. In my regular life, those are not people I would regularly intersect with, but because I’m very acutely aware of the lack of justice in the justice system—and also because I’ve worked in prison and in jail, and know how little humanity there is there—I feel like I need to intentionally engage with people in order to let them know they are human, and what they’re feeling is not crazy, and there are people who care, and they are not alone—any of these could be the thing someone holds onto to keep sane.

There’s no magic pill or magic wand that I can wave, but if EVERYONE does SOMETHING, imagine what we could accomplish as a collective. If everyone doesn’t go back to their little world and go “Well that was nice; I learned that,” and just keep it to themselves. I always tell my students, “Knowledge is not yours until you give it away.” And that doesn’t mean you have to be a teacher by profession, but that what you know you need to share with other people. That’s how you know you know it, and it belongs to you. It’s not just something somebody taught you—it belongs to you.

There are organizations that people can become members of. There’s work they can do in their own communities, even if their community is fairly homogenous—even in communities that look the same, there’s still a lot of diversity that goes on with regard to class, with regard to religion, with regard to education, with regard to gender. So as long as you’re working to dismantle this thing—which I believe is one of the curses that America deals with as a nation—as long as you’re doing what you can do where you are, we are going to change it. In an instant? No.

Is it going to be easy? No.

But if you are steady and intentional, you will see change, and I am a witness. You will see change.

There has been a lot of talk in CMN lately about songs that have racist histories—kids may not understand the references, but we still know, for example, that those melodies used to have different words, or the songs have some kind of racist tint. What do you advise people to do about a work of art that has an uncle tom issue?

12 Nursery Rhymes You Didn't Know Were Racist

(Content Note: This video contains racist images and language.)

I feel that when we know better, we need to do better. There are certain things that need to be retired to the bookshelf of history. We reference it—we even take it down and teach it in the context of history, but we don’t use it. I go to museums to see the things that I cannot experience anymore and wouldn’t want to, but that are important for me to know because it’s part of my history. I don’t want to wipe it away like it never happened. It’s like people wanting to take out the n-word from Mark Twain’s novels: I’m totally against that, because it’s a revision of a history that actually happened, and that people like my grandmother told me about. So, you’re kind of messing with my head when you start whitewashing that stuff.

The idea of history, I think, is to learn from it, to be informed by it, to not be harmed by it anymore. I shouldn’t have to be harmed by the legacy of lynching, for example. In Richmond, on that Monument Avenue, there are a lot of huge trees. And I, particularly in the evening, cannot go down that street and see those Civil War generals lit up, and not think about black bodies hanging from those trees. And yet those black bodies are not in any way memorialized, remembered, spoken of. They’re just forgotten as if it didn’t happen.

I cannot see those Civil War generals lit up and not think about black bodies hanging from those trees. And yet those black bodies are not in any way memorialized, remembered, spoken of. They’re just forgotten as if it didn’t happen.

The lynching memorial that just opened in Alabama—that will do something to unpack the trauma, to say, “Yes, this was horrendous, and it did happen, and we are recognizing that.” And perhaps, then when I go to the meditation garden I can weep and I can let go of some of that, and thereby be healed or on the road to healing. And I think that our history should do that for us. But if we don’t put those songs, those characters, where they belong, we can’t expect young children to do that.

I remember coming home from school singing “Jump down, turn around, pick a bale of cotton.” My mother said, “Where did you hear that?” I said, “The music teacher at school. We’re going to sing it at the annual blah blah blah,” and she said, “Oh no you’re not.” And I was like, “But why?” We had movement to it; we did this whole choreography. I was a performer early in my life and I was having fun!

It immediately traumatized my mother. I recognize that as an adult, but back then I didn’t; she was just being mean as far as I knew. My mother marched down to that school, and we did not sing that song.

Like I said, when we know better, we have to do better. If we continue not to do better, what does that make us?

In terms of choosing songs or choosing stories to share with kids, what can we do, in a positive sense, to use art to make those connections or learn about other people?

The idea is to teach the truth of history from a variety of perspectives. When I was in school, we learned only one perspective. We didn’t read Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. We didn’t hear the voices of enslaved people talking. We only heard from people like Harriet Beecher Stowe talking for them. What we should be attempting to do is to bring culturally inclusive perspectives to whatever art we offer. Those songs that are inherently racist, sexist, xenophobic, homophobic—we need to stop promoting those things. We’re artists. We need to create NEW things. The song “Glory” from the movie Selma—Common does the rap and John Legend does the music—that’s an example of merging the old and the new together, because the references in the rap lyrics are about the past. As young people sing those lyrics, they’re going to be saying things they might not recognize, so then they’re going to have to research and study that. That’s part of what our role is: to make them curious about finding out, and recognizing that there are things they need to learn. But by no means should we reinforce the things we are trying to deconstruct.

Thank you so much. I can’t wait to see you in Ohio!

Yeah, me too! It’s going to come faster than we know!

Hear Dr. Tawnya Pettiford-Wates’s keynote address at the 2018 CMN Annual International Conference at Sawmill Creek Resort, October 12–14.