Photo: Sandy Morris

Photo: Sandy Morris

Music, Story, Activism

An Interview With Nancy Schimmel

by Sally Rogers

I believe I first met Nancy Schimmel through either People’s Music Network or CMN. But I remember meeting an unassuming and gentle person, kind, welcoming, and warm to all those around her. I remember best her storytelling prowess. She could hook you into a story as fast as a frog can snag a fly, and keep you there right through to the end. I bought her book, Just Enough to Tell a Story, to teach myself some of the tricks of the trade and learned to tell her story, “The Yam Thief.” Then I learned her song, “1492,” which is THE best answer to the travesty of Columbus Day (now Indigenous People’s Day in many communities). Nancy follows in the footsteps of her mother, the late Malvina Reynolds, as a songwriter who can tackle difficult subjects with cleverness and commitment. She never speaks down to children, and respects their keen intelligence. Heck, she treats us ALL as equals and quietly and fervently nudges us to make the world a better place, as she is busy doing.

It was truly an honor to be asked to do this interview with Nancy. Although we were a continent apart, it was like sitting in her living room with a cup of tea, having a friendly conversation as we reminisced about her life and involvement with CMN. I hope you enjoy this glimpse into Nancy’s vibrant life, full of music, story, and activism.

Sally: Nancy, you are the second in your family to receive the Magic Penny award: your mom was our first and the reason for the name. How did you get involved in CMN to begin with?

Nancy: I don’t know the date of that outdoor circle where I was first introduced to CMN. I’m pretty sure it was at a People’s Music Network gathering. What I remember about it is that we were all going around the circle saying something, I forget what. And we had, like, two minutes, to say it. And so, I think it was Sarah Pirtle who set this up so that someone was timekeeper, and when the time was up they started humming, and whoever heard them hum started humming. Until enough people were humming that the person who was talking realized their time was up. And if we were so fascinated with what they were saying, I suppose we wouldn’t think to hum! Anyway, if that didn’t work and they kept talking and the timekeeper needed to do another nudge, she was to start making kissing noises, and then we would all pick that up. So, everyone would be going mwah-mwuh! [kissing sounds] and that meant time was up! It was effective, loving goofiness. CMN people do nutty things, and we all become more family that way.

I didn’t go every year to PMN but I went a few times. We had something called Freedom Song Network (FSN) out here, so it’s not like I didn’t have a political music thing to go to. I’m pretty sure Bonnie [Lockhart] was part of FSN. And that’s how I met Hali Hammer.

She’s one of the Occupellans, along with Bonnie, Betsy [Rose], and me.

Tell me about Occupella. It came out of the Occupy movement, I assume.

Occupella (Hali Hammer, Bonnie Lockhart, Nancy) and friends at an anti-fracking march in Oakland

Occupella (Hali Hammer, Bonnie Lockhart, Nancy) and friends at an anti-fracking march in Oakland

Bonnie suggested that some people she knew get together and have Song Circles once a week at Occupy Berkeley and once a week at Occupy Oakland. We did them during the noon hour. We would just sit around and sing, and whoever felt like joining us did, and out of that group came Occupella. We go to rallies and marches—we arrange with the people who are organizing, or they ask us, or whatever. And we lead people in singing; we have song sheets. So, the idea is not that it’s a performance but that it involves everybody. And if it’s a march, people drop out for a while, sing with us, and then go on. The songs that we use are mostly parodies, or they’re old-time movement songs—“Which Side Are You On?” and songs like that. All the parodies are online so anyone can use these anywhere: occupella.org. We didn’t feel like it was any use making a printed songbook ’cause we keep changing things and writing new songs. We have, like, four different versions of our “Stop the Pipeline” song. The situation keeps changing, so we change.

Let’s talk a little bit about your growing up, because you certainly were growing up in an interesting home. Your dad was a union activist and a storyteller himself. And of course, your mom wrote songs, but I guess she didn’t start writing songs until actually you were out of the house?

She was writing songs when I was in junior high and high school. She wrote some songs for the Henry Wallace campaign. That was in ’48. I graduated from high school in ’52. So, she started writing songs and she sang them at hootenannies with a bunch of other people, or she sang them at meetings, at rallies—events like that. She didn’t start doing concerts until I was through college and married.

But you certainly grew up exposed to a lot of musical activism, music “doing a job.”

Yes, I did. People’s Songs started right after the Second World War. It started in New York but it had a Los Angeles branch. Earl Robinson was one of the people there who was central to that. And so, we were living in Long Beach and we would go into Los Angeles for hootenannies. Or we would have local ones. If it was in Long Beach, it would be at the Masonic Temple. People would rent a room to have a meeting, and I remember we kids would generally ride up and down in the self-service elevator. You know, kind of fooling around, but if there was singing going on, we’d be there.

I just love the idea of you being a little tyke and having all this going on around you. When you were in high school, was it still interesting, or did you sort of fight against it?

All-ages song circle on MLK Day, 2015, at Fruitvale Station in Oakland (Photo credit: Cathy Cade)

All-ages song circle on MLK Day, 2015, at Fruitvale Station in Oakland (Photo credit: Cathy Cade)

When I was in high school, my mother ran for City Council. This was when I was a junior, ’cause I was taking United States History and Government. And there was another girl there whose father was running for City Council. So, the teacher had us each give an oral report about that. The other girl talked about the campaign and what it was like to have her father doing this stuff. And I did a campaign speech about the issues. My father had trained me. When I was really little he would put me up on the wood box by the fireplace and have me raise my fist and say, “We want more pork and beans!” So, we were at a Socialist picnic—and I have no memory of this, I was too young to remember it—we were at a Socialist picnic and there were speeches. And he noticed that I was very interested.

He asked me if I wanted to make a speech. I said, “Yes!” So, he took me up on his arm and took me up to the chair, and said, “This little comrade wants to make a speech.” And the guy said, “Yeah, sure, put her up on the platform.” So they did, and I raised my fist in the air and said, “We want more pork and beans!”

At the same time I was learning to talk, I was learning to speak, which is different. And also, my father was a carpenter, and he was working on a dam they were building up in the Sierras, and we went up to visit. He would put me up on the bar in the local watering hole, and put a nickel in the jukebox, and I would dance. So, it was politics and art all the way from the very beginning!

Clearly, your early exposure to public speaking helped you along as a storyteller. Did you start telling stories in high school, or later?

I’d say later. I was singing with kids when I was in high school and college ’cause I was a summer camp counselor. Afterward, I was doing some singing with kids in day camp. And that is where I started doing Pete Seeger’s “Foolish Frog” story. So, that’s really the first story that I told. It’s such a useful story because you can get any-age kids involved. It wasn’t until later that I started just telling stories. When I went to library school, I took a storytelling class, because I wanted to be a children’s librarian, and librarians do story hours. I liked working with children, but it was a job that fit me because I know a little bit about a lot of things; you’re dealing with all subjects with the kids.

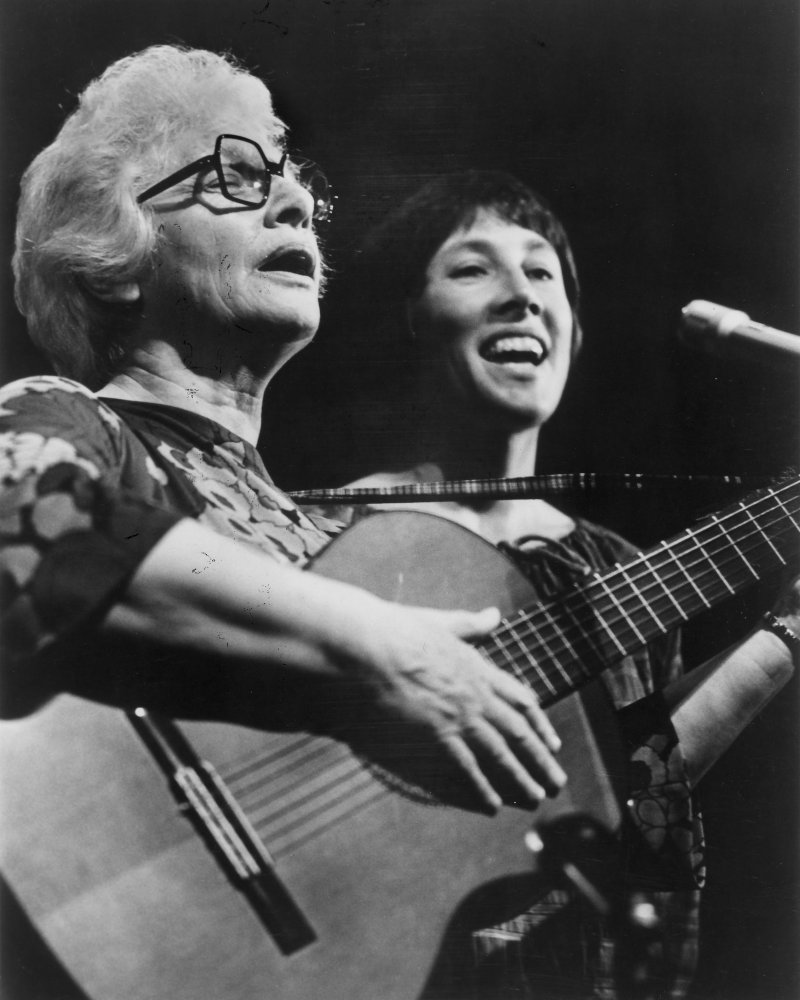

Nancy on tour in Japan with her mother, Malvina Reynolds, in 1970

Nancy on tour in Japan with her mother, Malvina Reynolds, in 1970

While taking the class, I wanted to tell “The Little Red Hen” as one of the stories. I went to the library and I looked at a book, and at the ending, the Little Red Hen didn’t just say, “No, I will eat the bread.” It had her sharing the bread with her children! She can’t just have it on her own after she did all the work?! She has to be a mother? So, I went to my mother’s place and said, “Tell me the Little Red Hen.” Somehow I knew it would be right if she told me the story. ’Cause that’s the way I had learned it when I was a kid. And she told it right! So, I went and told it right and she went and wrote the song, “The Little Red Hen.”

I was a children’s librarian in a public library. I also did two years as a school librarian and a short stint as a reference librarian. I was toying with the idea of quitting, because I wanted to explore something else, so I took a leave of absence. Guy Carawan was touring out here and invited me to go to Highlander at the time of the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough [Tennessee]. It was just a revelation! I met the Folk Tellers [cousins Connie Regan-Blake and Barbara Freeman]; one had been a librarian and the other had been hired by the library to tell stories, and then they had quit and gone on the road. And I thought, “Well, I’m a librarian. I tell stories at the library. I could quit and go on the road.” [laughs] I had, between 1974 and 1975, left my husband, come out as a lesbian, and discovered that you could be a storyteller as a job.

My first partner was organizing feminist librarians into the organization called Women Library Workers. We started traveling. I was helping her organize and she was helping me tell stories. Our first tour was in ’76; we went all across the country telling stories in women’s bookstores like Women and Children First in Chicago and A Room of One’s Own in Madison. It was an exciting time to be on the road.

And I think that was the time when storytelling as a performance art really was being accepted as a thing to do for grownups. It wasn’t just for kids.

When I’d say I was a storyteller they’d say, “Oh, you tell stories for kids.” I’d say “Well yeah, and to adults.” You still had to explain that. But I did do a lot of storytelling to kids. I also did a little bit of teaching storytelling to kids as an artist in residence in schools.

When did you write the storytelling book Just Enough to Tell a Story? I met you and bought your book and devoured it.

That came out of teaching storytelling in Madison. I was making all these handouts on the ditto machine and thought it would be easier if I had a book, so I went home and wrote one and self-published it. The first one was in 1978.

If I had to guess, I’d say that all of your storytelling performances included some singing?

Pretty much, depending on the age of the kids. But I really did start writing songs after I left my husband. I started writing poetry. We were together for seventeen years, and I think I wrote one poem in all that time.

You have one daughter?

Not from that marriage. I got pregnant in college and gave her up for adoption. We got back together when she was thirty-seven. She grew up in a household where the people appreciated art but didn’t create it. And she did it. So, she was glad to know where that came from. My mother was dead by the time she and I met. But she did get a chance to meet her aunt who was a photographer. She got the connection with music from me and visual art from her aunt. I think it really helped her become more comfortable with herself. She’s coming to the conference.

Video of Nancy’s “Vegetable Song” with animation by her daughter, Nancy Ibsen

I do some visual art and craft myself, but I’ve tended to neglect it of late. CMN inspired me to do two quilt squares, the second of which I’m particularly happy with. It’s the dragon square on the latest CMN quilt, and it was inspired by “I Think of a Dragon,” which I wrote with Judy Fjell. The song was inspired by Mara Sapon-Shevin and her work on behalf of young people who have been bullied.

Some of your songs have really taken off. “1492” for one. It was in the Teaching Tolerance book and I recorded it. You want to tell the story about that?

That is my most widely known song. Candy Forest and I recorded it. A Bay Area local group, Grupo Raiz recorded it. You did, and yours also got onto the anthology that John McCutcheon put together. So, it’s really gone places. I wrote that in 1991 because 1992 was going to be the 500th anniversary and someone in 1991 had put out a newsletter asking what are we going to do about this? There was a local committee that was looking at what was happening here.

An exhibit at the science museum here compared the science in the New World and the Old World. You know, they had a lot of the astronomy here with Chichen Itza and places like that. So, they were doing this exhibit and I went around with the people on the committee, who were both Native American and not, talking and critiquing how things were being presented. One exhibit talked about human sacrifice as part of their religion. Our committee was saying, “yes, and they were doing that at the same time in Europe, with the Inquisition, so could you adjust your exhibit to show that comparison?’ It was really an eye-opening time.

Animation of “1492” as recorded by Sally Rogers and featured in the 2003 Teaching Tolerance anthology, I Will Be Your Friend: Songs and Activities for Young Peacemakers

I wrote the song and ran it by some Native American people here, and also a Native American storyteller I knew from storytelling, and they approved. I happened to be at KPFA when Louise Erdrich and her husband, Michael Dorris, were going to be on the show. I showed it to them and they approved of it too. Oh, and Berkeley declared that what had been Columbus Day would now become Indigenous Peoples Day. So, after all these years of it being Indigenous Peoples Day and the schools changing their teaching, some teachers and parents recently objected to that song because of the line “it was a courageous thing to do.” They felt we shouldn’t be praising Columbus. Even though the song is skeptical of Columbus, they wanted something stronger than that.

I’m not sure how I feel about that one.

I was happy to change it, actually. Partially because I didn’t want anyone else to change it because they wouldn’t do it right. [laughs] So I explain the background: He thought that the world was smaller in diameter than it actually was, which is why he thought he could sail from Europe to Asia. But they probably wouldn’t have made it. I mean if there had only been ocean. He thought he could have made it because he thought the world was smaller. In truth, the Greeks knew that it was bigger than he thought it was! He was not paying attention to science. Sort of like climate change.

Anyway, I say something about that and then sing “he didn’t know what he thought he knew.”

What I like about that line is it ties into what you say later.

“He didn’t find what he thought he found.” I like that parallel too. So, I didn’t mind changing that. But then someone in Ohio, where they have a city named Columbus, she liked it with the courageous thing to do, because it kind of snuck it into people.

I’m also in charge of changing things to my mother’s songs, when people call and ask for approval. Some of them are okay, but 90 percent of them are not. Not that it doesn’t need changing, but the change doesn’t sound good and it doesn’t sound the way my mother would have done it. She’s my mother and I know how she would have done it. I mean, I don’t know, but. . . .

How did they end up with your mother’s song “Little Boxes” for [the television program] Weeds?

We found out that the producers of the show were fans of the song and wanted it. They used my mother’s recording of it for the first season or two. And then they got all these other people to record it, and also used some other recordings of it that had already been made, including the one in French that the McGarrigle Sisters did. The translation was done by Graeme Allwright. When my mother heard that translation she said, “It sounds better in French than it does in English!” [sings] “Petites boîtes très étroites / Petites boîtes faites en ticky-tacky . . . ” She was also amused when someone translated it into Esperanto because she thought Esperanto was a ticky-tacky language! Oh, and she was very pleased when “ticky-tacky” got into the dictionary!

Wow! I say you can die and go to heaven when that happens!

It’s one thing to get a PhD, but it’s entirely something else to get a word in the dictionary!

Opening credits for Weeds with theme song “Little Boxes” by Malvina Reynolds

What hints would you give to songwriters and storytellers about their craft?

Well, I find that collaborating is very useful. The other person needs to say “Oh really? Well how would it sound this way?” For instance, for one of the songs that Judy Fjell and I wrote together, we were going back and forth with this one verse. There was one line that just wasn’t working. She would do one and I didn’t like it, and I would do one and she didn’t like it. Finally, I got a line that we both liked. But I wouldn’t have gotten there without her nudging me and experimenting with all these other lyrics. She was doing the tune and she kept at me till we got the right words.

I was forty when I started writing songs and fifty when I met Candy Forest. She knew my mother’s music and loved it and wanted to talk to me, so that’s how we got acquainted. That’s when I started getting serious about writing children’s songs, because she had a small children’s chorus. So, there was a place for the songs to go, which is stimulating! Sometimes I would write the words and she the music, and sometimes I would write both or she would write both. We produced three albums together.

A friend of hers, Nancy Fox, said, “You really should go to Laney and take some music courses.” Laney is a junior college here in Oakland with a very good music department. And so, I went to Laney and learned some music theory. I took the basics and harmony and a course where you analyze different musical compositions. It really helped. And actually, my mother had done the same thing at just about the same age—gone back to college to take a few courses in music theory.

When she was signing up, the person signing her up said “You can’t sign up for that course. You don’t have the prerequisite.” She said “I already have a PhD.” And he said “Oh, well then . . .” She didn’t say it was in English! [both laugh] She said that was the only time in her life that she used her PhD. [bigger laughter from both] Because when she got it, during the depression, she was a socialist, and she couldn’t get a job.

What haven’t we talked about yet that you want to talk about?

Marianne Barlow, Bonnie Lockhart, Betsy Rose, Nancy, Leslie Hassberg, Judy Fjell, and Hali Hammer singing one of Nancy’s bee songs at her 80th birthday show (Photo credit: Maureen Barnato)

Marianne Barlow, Bonnie Lockhart, Betsy Rose, Nancy, Leslie Hassberg, Judy Fjell, and Hali Hammer singing one of Nancy’s bee songs at her 80th birthday show (Photo credit: Maureen Barnato)

When I was touring doing storytelling, I was kind of specializing in stories with active women in them. Actually, I had started on that when I was a librarian. The Association of Children’s Librarians in Northern California did a list of picture books and children’s books that had strong women characters. Because, at that time, you looked at picture books and boys were doing things and girls were watching them. There was some good stuff, but we were trying to put it forward.

One more thing I want to say, that’s not about me and not about my mother, but about CMN. I have made such good friends there and I have found such good songs! And I particularly want to mention “So Many Ways to Be Smart” [by Stuart Stotts]. Because I glommed onto it when it was first written because of the testing, and it’s only gotten worse, and worse, and worse! And that’s such a good answer to that. I went to a Kids and Creeks Conference here years ago—this wonderful organization that puts together kids and creeks—and what could be better?! You know, messing around in mud and learning about watersheds. So, they have this conference and these fifth graders were making a presentation to this whole auditorium of teachers and other grown-ups. In Marin County, they have a thing where you can adopt a species that’s in trouble in some way.

So, their group adopted this freshwater shrimp that was having a hard time because they need shade in the stream to be able to live and reproduce. They were huddling under bridges, because the cattle were eating the vegetation along the streams. The kids’ two jobs were to convince ranchers to fence off the streams and to plant native plants along the streams. Some of them were writing to the newspapers. Some were looking to talk to ranchers. Some were planting the native plants. And they had different committees.

So, I said, “I have two questions. One is: Have you had experience with committees? In school or in Scouts or anything like that?” “No, that just seemed like the way to do things, for people to do what they were good at or interested in.”

And then I said, “This question is for the teacher: I’ve read about multiple intelligences; you probably have too, were you thinking about teaching this way?” And she said, “No, but you know, when you deal with the real world you need all the intelligences.” Wow!

Is there anything else you want to say about your relationship to CMN?

I love that it exists! And that it is what it is! I really appreciate that it has stayed true to its roots in the People’s Music Network—changing as things change, but keeping the core values.

Come celebrate Nancy Schimmel as she receives the Magic Penny Award at

the CMN 2019 Annual International Conference!

Special thanks to Mara Beckerman, Dorothy Cresswell, and Lisa Heinz for transcribing the interview.